Last Spike

Artifact

Image

Video

Audio

Activities

Activities

LOOK

Look closely at this object. What do you think it was used for? Read the Historical Context below to verify your answer.

Details

Materials

Materials - Sterling silver

- Granite

- Glass

- Fibre

Historical Context

Choose one of the three levels below to match your needs.

- This is a reproduction of the silver ceremonial “last spike” of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), which was completed in 1885.

- Canada’s transcontinental rail line connected the CPR from the Pacific Coast to Montréal, and the Grand Trunk and Intercolonial railways from Montréal to Halifax.

- Constructing the railway required many workers, including 15,000 Chinese men and boys. They worked in extremely dangerous conditions, and many were killed.

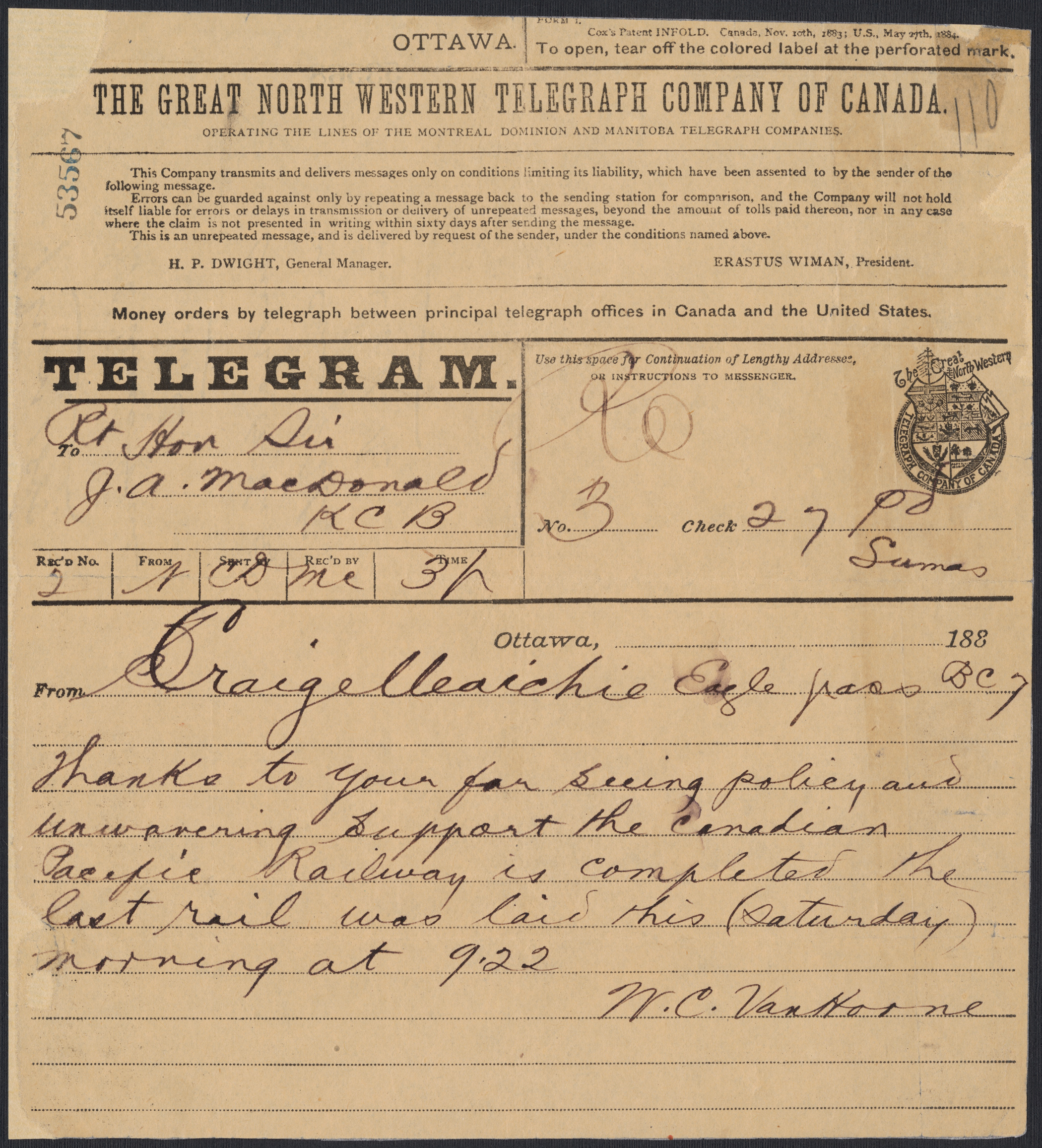

Scroll through the media carousel above to see a picture of Donald A. Smith driving the last spike, and a telegram advising Prime Minister John A. Macdonald of the completion of the railway.

This is a reproduction of the silver ceremonial “last spike” presented by the Governor General of Canada to William Cornelius Van Horne, the General Manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in 1885. The railway was completed on November 7, 1885.

Once complete, Canada’s transcontinental rail line connected the CPR from Port Moody (on the Pacific Coast) to Montréal, and the Grand Trunk and Intercolonial railways from Montréal to Halifax.

Construction of the CPR was a vast undertaking. It took the labour of many thousands of workers to complete the 5,000-kilometre track. In British Columbia, an estimated 15,000 Chinese men and boys worked on the railway. They worked in extremely dangerous conditions, and many were killed in blasting accidents, rockslides, mudslides and falls.

This is a reproduction of the ceremonial “last spike” presented in 1885 to William Cornelius Van Horne, General Manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), by the Governor General of Canada. The railway was completed on November 7, 1885, when CPR director Donald A. Smith drove in the last spike at Craigellachie, British Columbia.

Once complete, Canada’s transcontinental rail lines connected the CPR from Port Moody (on the Pacific Coast) to Montréal. From Montréal, the Grand Trunk and Intercolonial Railways completed the network to Halifax.

Sir John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives had won the 1878 election on the promise of a “national policy” that included completion of a transcontinental railway. Construction of the CPR was a vast undertaking. It took the labour of many thousands of workers to complete the 5,000-kilometre track through forests and mountains, and across the Prairies.

Most CPR labourers came from Europe, the United States and eastern Canada. In British Columbia, an estimated 15,000 Chinese men and boys worked on the railway, often in extremely dangerous conditions. Many were killed in blasting accidents, rockslides, mudslides and falls. CPR labour contractor Andrew Onderdonk estimated that three Chinese workers died for every kilometre of track laid in the Fraser Canyon alone.

- This is a reproduction of the silver ceremonial “last spike” of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), which was completed in 1885.

- Canada’s transcontinental rail line connected the CPR from the Pacific Coast to Montréal, and the Grand Trunk and Intercolonial railways from Montréal to Halifax.

- Constructing the railway required many workers, including 15,000 Chinese men and boys. They worked in extremely dangerous conditions, and many were killed.

Scroll through the media carousel above to see a picture of Donald A. Smith driving the last spike, and a telegram advising Prime Minister John A. Macdonald of the completion of the railway.

This is a reproduction of the silver ceremonial “last spike” presented by the Governor General of Canada to William Cornelius Van Horne, the General Manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in 1885. The railway was completed on November 7, 1885.

Once complete, Canada’s transcontinental rail line connected the CPR from Port Moody (on the Pacific Coast) to Montréal, and the Grand Trunk and Intercolonial railways from Montréal to Halifax.

Construction of the CPR was a vast undertaking. It took the labour of many thousands of workers to complete the 5,000-kilometre track. In British Columbia, an estimated 15,000 Chinese men and boys worked on the railway. They worked in extremely dangerous conditions, and many were killed in blasting accidents, rockslides, mudslides and falls.

This is a reproduction of the ceremonial “last spike” presented in 1885 to William Cornelius Van Horne, General Manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), by the Governor General of Canada. The railway was completed on November 7, 1885, when CPR director Donald A. Smith drove in the last spike at Craigellachie, British Columbia.

Once complete, Canada’s transcontinental rail lines connected the CPR from Port Moody (on the Pacific Coast) to Montréal. From Montréal, the Grand Trunk and Intercolonial Railways completed the network to Halifax.

Sir John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives had won the 1878 election on the promise of a “national policy” that included completion of a transcontinental railway. Construction of the CPR was a vast undertaking. It took the labour of many thousands of workers to complete the 5,000-kilometre track through forests and mountains, and across the Prairies.

Most CPR labourers came from Europe, the United States and eastern Canada. In British Columbia, an estimated 15,000 Chinese men and boys worked on the railway, often in extremely dangerous conditions. Many were killed in blasting accidents, rockslides, mudslides and falls. CPR labour contractor Andrew Onderdonk estimated that three Chinese workers died for every kilometre of track laid in the Fraser Canyon alone.

Summary

- This is a reproduction of the silver ceremonial “last spike” of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), which was completed in 1885.

- Canada’s transcontinental rail line connected the CPR from the Pacific Coast to Montréal, and the Grand Trunk and Intercolonial railways from Montréal to Halifax.

- Constructing the railway required many workers, including 15,000 Chinese men and boys. They worked in extremely dangerous conditions, and many were killed.

Scroll through the media carousel above to see a picture of Donald A. Smith driving the last spike, and a telegram advising Prime Minister John A. Macdonald of the completion of the railway.

Essential

This is a reproduction of the silver ceremonial “last spike” presented by the Governor General of Canada to William Cornelius Van Horne, the General Manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in 1885. The railway was completed on November 7, 1885.

Once complete, Canada’s transcontinental rail line connected the CPR from Port Moody (on the Pacific Coast) to Montréal, and the Grand Trunk and Intercolonial railways from Montréal to Halifax.

Construction of the CPR was a vast undertaking. It took the labour of many thousands of workers to complete the 5,000-kilometre track. In British Columbia, an estimated 15,000 Chinese men and boys worked on the railway. They worked in extremely dangerous conditions, and many were killed in blasting accidents, rockslides, mudslides and falls.

In-Depth

This is a reproduction of the ceremonial “last spike” presented in 1885 to William Cornelius Van Horne, General Manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), by the Governor General of Canada. The railway was completed on November 7, 1885, when CPR director Donald A. Smith drove in the last spike at Craigellachie, British Columbia.

Once complete, Canada’s transcontinental rail lines connected the CPR from Port Moody (on the Pacific Coast) to Montréal. From Montréal, the Grand Trunk and Intercolonial Railways completed the network to Halifax.

Sir John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives had won the 1878 election on the promise of a “national policy” that included completion of a transcontinental railway. Construction of the CPR was a vast undertaking. It took the labour of many thousands of workers to complete the 5,000-kilometre track through forests and mountains, and across the Prairies.

Most CPR labourers came from Europe, the United States and eastern Canada. In British Columbia, an estimated 15,000 Chinese men and boys worked on the railway, often in extremely dangerous conditions. Many were killed in blasting accidents, rockslides, mudslides and falls. CPR labour contractor Andrew Onderdonk estimated that three Chinese workers died for every kilometre of track laid in the Fraser Canyon alone.