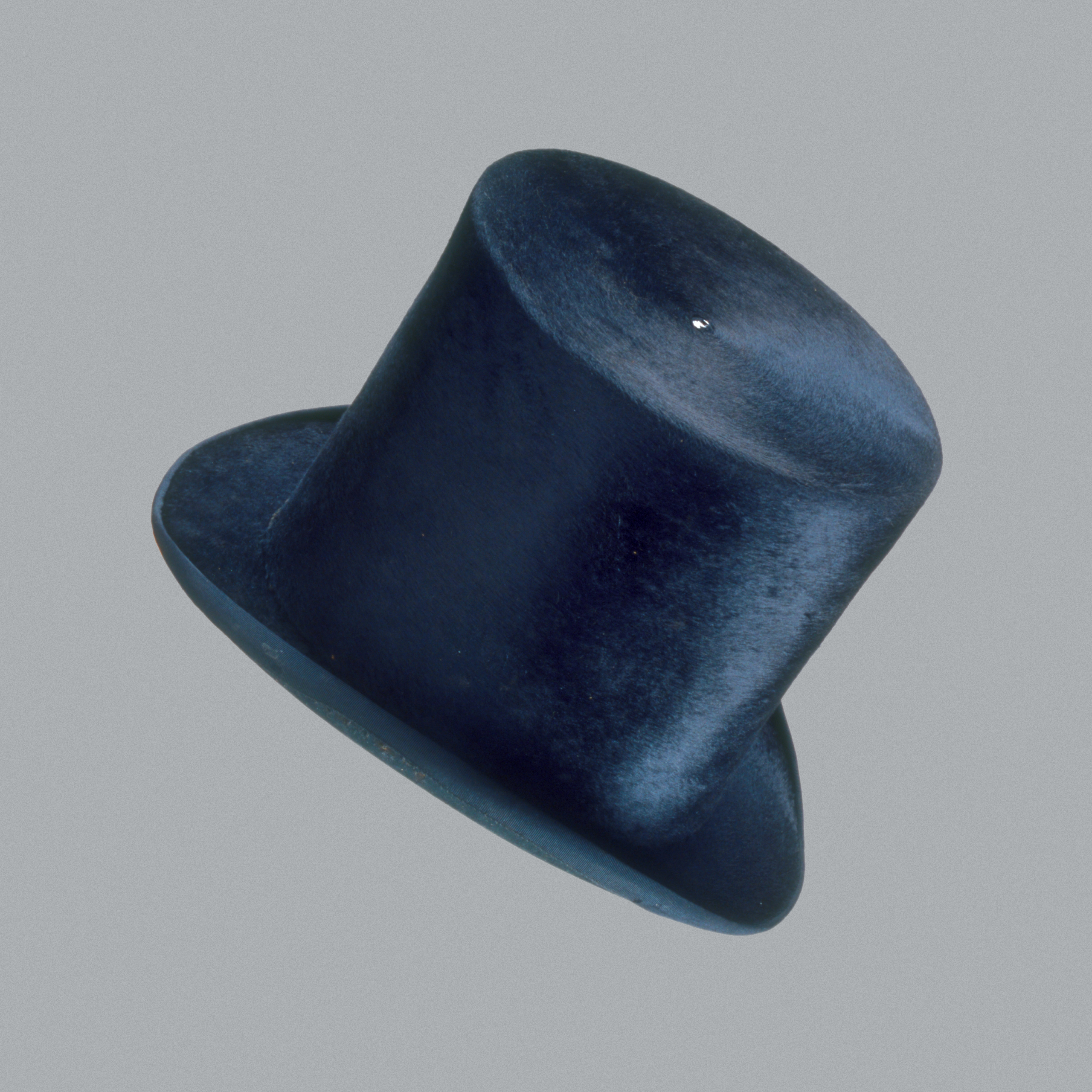

Beaver Felt Hat

Artifact

Image

Video

Audio

Activities

Activities

LOOK

Look closely at this object. What do you think its purpose is? Verify your answer by reading the Historical Context below.

THINK

Look at this object and read the Historical Context below. What questions do you have about this object, or the stories it represents? Share your questions with a partner.

Details

Materials

Materials - Beaver fur

- Silk

- Wool

Historical Context

Choose one of the three levels below to match your needs.

- This felt hat was made from beaver pelt, silk and wool.

- Such hats were a fashion staple for men of status between the 17th and the early 19th centuries.

- The hats were so popular, that English and French fur trappers competed fiercely, sometimes violently, for access to beavers.

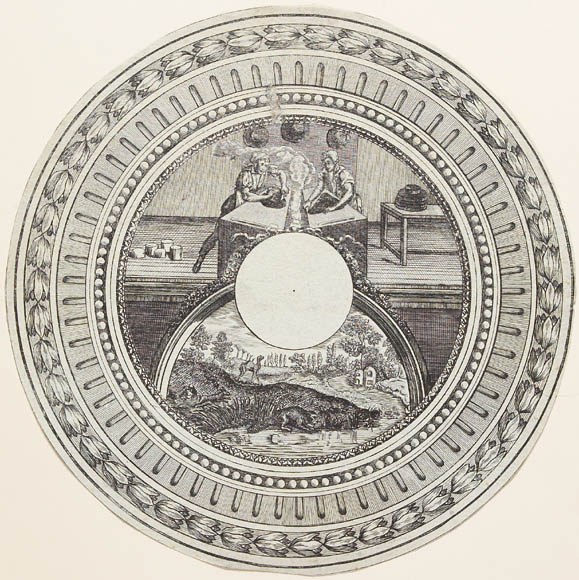

Scroll through the media carousel above to see a picture of a beaver, types of beaver felt hats, a hat box label that illustrates the hat making process and Rembrandt’s self-portrait wearing a beaver felt hat.

This felt hat was made from beaver pelt, silk and wool. Such hats were a fashion staple for men of status between the 17th and the early 19th centuries.

During this period, European fur traders prized beaver pelts above all other North American furs. French and English fur traders competed for access to this internationally sought-after commodity.

Since the early 1600s, the French had traded in beaver pelts with Indigenous peoples, but they soon faced fierce, and sometimes violent, competition from English traders.

In 1670, England’s King Charles II granted a royal charter to a fur-trading venture called the Hudson’s Bay Company. This allowed the company to establish fur-trading posts over a vast area on the south shore of Hudson Bay.

This felt hat was made with beaver fur, silk and wool. Hats like these were a fashion staple for men of status between the 17th and early 19th centuries.

During this period, European fur traders prized beaver pelts above all other North American furs. French and English fur traders competed for access to this internationally sought-after commodity. Fashion fuelled the competition: European hatters coveted beaver pelts for their soft underfur, which could be transformed into a soft, malleable and water-resistant felt, suitable for gentlemen’s hats such as this.

After establishing a permanent presence in the St. Lawrence Valley during the early 1600s, the French traded in beaver pelts with Indigenous peoples; however, they soon faced fierce, and sometimes violent, competition from English traders. In some cases, the rivalry brought new opportunities for Indigenous peoples, some of whom became hunters, trappers and middlemen in the trade.

There was a turning point in 1670, when England’s King Charles II granted a royal charter to a fur-trading venture called the Hudson’s Bay Company. This allowed the company to establish fur-trading posts over a vast area on the southern shore of Hudson Bay. In return, the company paid the king an annual rent in hides from beaver and elk – the animals featured on the company’s coat of arms.

- This felt hat was made from beaver pelt, silk and wool.

- Such hats were a fashion staple for men of status between the 17th and the early 19th centuries.

- The hats were so popular, that English and French fur trappers competed fiercely, sometimes violently, for access to beavers.

Scroll through the media carousel above to see a picture of a beaver, types of beaver felt hats, a hat box label that illustrates the hat making process and Rembrandt’s self-portrait wearing a beaver felt hat.

This felt hat was made from beaver pelt, silk and wool. Such hats were a fashion staple for men of status between the 17th and the early 19th centuries.

During this period, European fur traders prized beaver pelts above all other North American furs. French and English fur traders competed for access to this internationally sought-after commodity.

Since the early 1600s, the French had traded in beaver pelts with Indigenous peoples, but they soon faced fierce, and sometimes violent, competition from English traders.

In 1670, England’s King Charles II granted a royal charter to a fur-trading venture called the Hudson’s Bay Company. This allowed the company to establish fur-trading posts over a vast area on the south shore of Hudson Bay.

This felt hat was made with beaver fur, silk and wool. Hats like these were a fashion staple for men of status between the 17th and early 19th centuries.

During this period, European fur traders prized beaver pelts above all other North American furs. French and English fur traders competed for access to this internationally sought-after commodity. Fashion fuelled the competition: European hatters coveted beaver pelts for their soft underfur, which could be transformed into a soft, malleable and water-resistant felt, suitable for gentlemen’s hats such as this.

After establishing a permanent presence in the St. Lawrence Valley during the early 1600s, the French traded in beaver pelts with Indigenous peoples; however, they soon faced fierce, and sometimes violent, competition from English traders. In some cases, the rivalry brought new opportunities for Indigenous peoples, some of whom became hunters, trappers and middlemen in the trade.

There was a turning point in 1670, when England’s King Charles II granted a royal charter to a fur-trading venture called the Hudson’s Bay Company. This allowed the company to establish fur-trading posts over a vast area on the southern shore of Hudson Bay. In return, the company paid the king an annual rent in hides from beaver and elk – the animals featured on the company’s coat of arms.

Summary

- This felt hat was made from beaver pelt, silk and wool.

- Such hats were a fashion staple for men of status between the 17th and the early 19th centuries.

- The hats were so popular, that English and French fur trappers competed fiercely, sometimes violently, for access to beavers.

Scroll through the media carousel above to see a picture of a beaver, types of beaver felt hats, a hat box label that illustrates the hat making process and Rembrandt’s self-portrait wearing a beaver felt hat.

Essential

This felt hat was made from beaver pelt, silk and wool. Such hats were a fashion staple for men of status between the 17th and the early 19th centuries.

During this period, European fur traders prized beaver pelts above all other North American furs. French and English fur traders competed for access to this internationally sought-after commodity.

Since the early 1600s, the French had traded in beaver pelts with Indigenous peoples, but they soon faced fierce, and sometimes violent, competition from English traders.

In 1670, England’s King Charles II granted a royal charter to a fur-trading venture called the Hudson’s Bay Company. This allowed the company to establish fur-trading posts over a vast area on the south shore of Hudson Bay.

In-Depth

This felt hat was made with beaver fur, silk and wool. Hats like these were a fashion staple for men of status between the 17th and early 19th centuries.

During this period, European fur traders prized beaver pelts above all other North American furs. French and English fur traders competed for access to this internationally sought-after commodity. Fashion fuelled the competition: European hatters coveted beaver pelts for their soft underfur, which could be transformed into a soft, malleable and water-resistant felt, suitable for gentlemen’s hats such as this.

After establishing a permanent presence in the St. Lawrence Valley during the early 1600s, the French traded in beaver pelts with Indigenous peoples; however, they soon faced fierce, and sometimes violent, competition from English traders. In some cases, the rivalry brought new opportunities for Indigenous peoples, some of whom became hunters, trappers and middlemen in the trade.

There was a turning point in 1670, when England’s King Charles II granted a royal charter to a fur-trading venture called the Hudson’s Bay Company. This allowed the company to establish fur-trading posts over a vast area on the southern shore of Hudson Bay. In return, the company paid the king an annual rent in hides from beaver and elk – the animals featured on the company’s coat of arms.