Chinese Immigration Act Certificate

Document

Image

Video

Audio

Activities

Activities

LOOK

Look closely at this object. What do you think it is? Verify your answer by reading the Historical Context below.

THINK

Read about Ann Fong in the Historical Context below. If you could ask her questions about her experience as a Chinese Canadian, what would they be?

Details

Materials

Materials - Paper

- Ink

Transcript

Transcription:

- Dominion of Canada

- Department of Immigration and Colonization

- Chinese Immigration Service

- Registration Certificate

- Section 18 Chinese Immigration Act 1923

This is to certify that__________, whose photograph is attached hereto, has registered as required by Section 18 of the Chinese Immigration Act, Chapter 38, 13-14 George V. Dated at ________________ on this _________day of _________192_

Controller of Chinese Immigration

This certificate does not establish legal status in Canada

Historical Context

Choose one of the three levels below to match your needs.

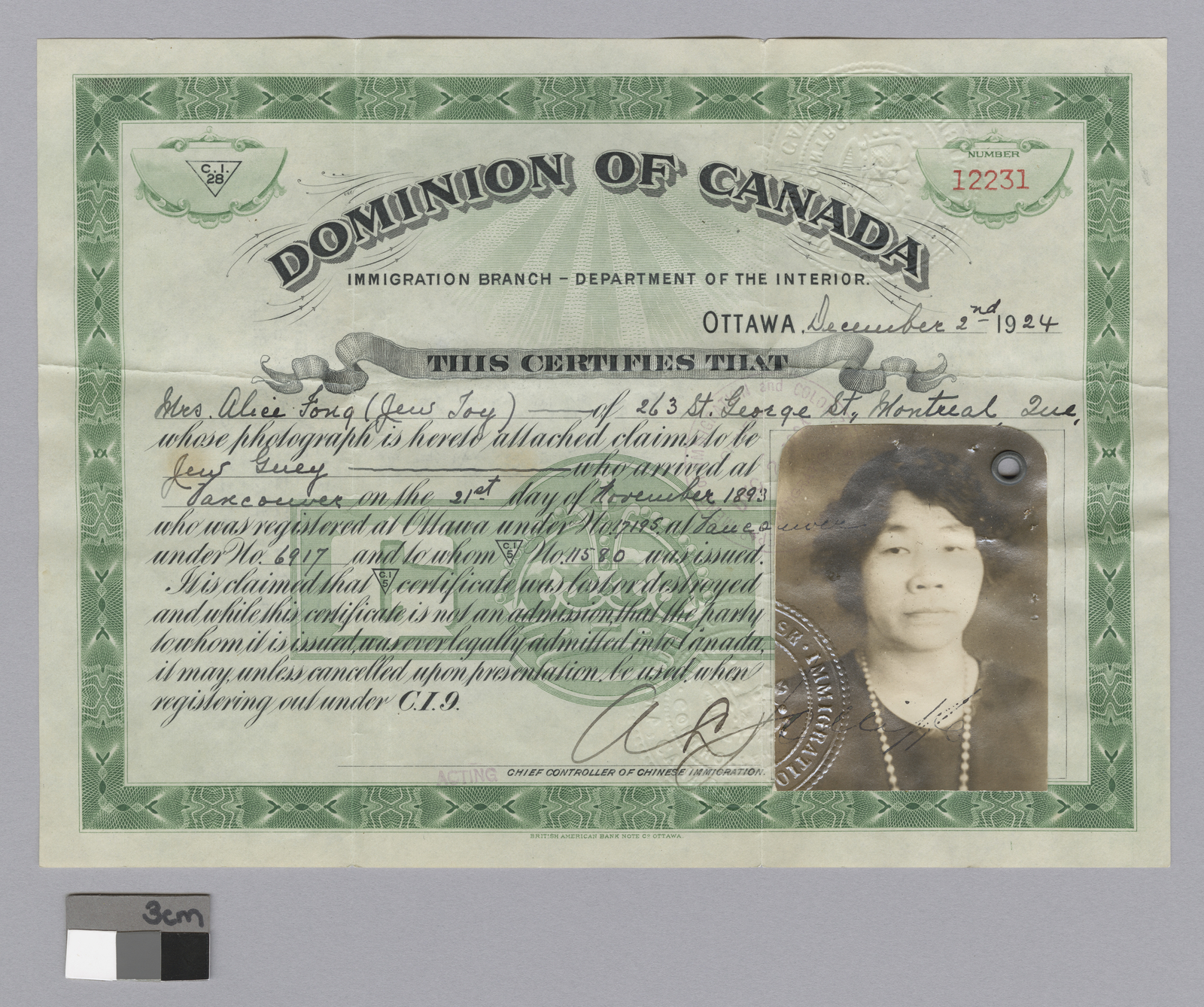

- This is a Chinese Immigration Act This certificate belonged to Ann Fong (b. 1916; d. 2016). The youngest of five children, Ann was born in Montréal in 1916, where she lived her entire life.

- In 1885, the government barred people of “Chinese or Mongolian race” from voting and imposed a special immigration fee — a head tax — on Chinese workers and their family members coming to Canada.

- The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 required “every person of Chinese descent or origin” living in Canada, including those born in Canada, to carry a Chinese Immigration Act certificate like this one. It also cut off any further immigration from China. Family members could no longer immigrate.

- On June 22, 2006, after many years of lobbying and demands for restitution by Chinese Canadians, the federal government apologized for the Chinese head tax.

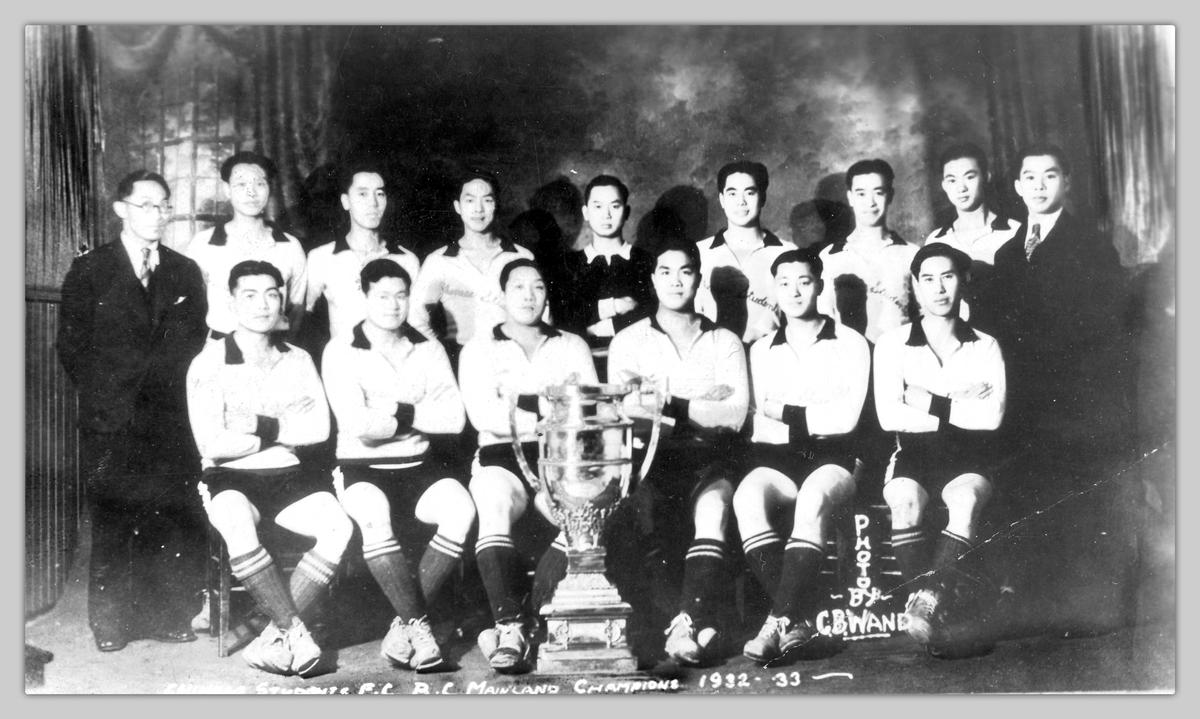

Scroll through the media carousel above to see a photo of Prime Minister Stephen Harper being presented with a ceremonial last spike by James Pon, a Chinese head tax payer, a group photo of the Chinese Students Football Club, and a photo of Lila Wong, Jean Suey Zee Lee and Marion Laura Mah at a citizenship ceremony in 1947.

This is a Chinese Immigration Act certificate. The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 required “every person of Chinese descent or origin” living in Canada, including those born in Canada, to carry a certificate like this one. Anyone who failed to produce such a certificate could be fined, imprisoned or deported.

Once the Canadian Pacific Railway was complete in 1885 (built largely by Chinese immigrant labourers), the government barred people of “Chinese or Mongolian race” from voting and imposed a special immigration fee — a head tax — on Chinese workers and their family members coming to Canada.

In 1923, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act. It effectively cut off any further immigration from China. Family members could no longer immigrate. Chinese Canadians maintained community ties and fought for their rights through a variety of community associations.

On June 22, 2006, after many years of lobbying and demands for restitution by Chinese Canadians, the federal government apologized for the Chinese head tax.

This certificate belonged to Ann Fong (b. 1916; d. 2016). The youngest of five children, Ann was born in Montréal in 1916, where she lived her entire life. Her father, Fong Monking, a merchant, immigrated to Canada around 1887 and her mother, Alice Chiu, immigrated in 1893 at the age of 7. Both were from Guangdong province in China.

This is a Chinese Immigration Act certificate. The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 required “every person of Chinese descent or origin” living in Canada — including those born in the country — to carry a certificate like this one. Anyone who failed to produce such a certificate could be fined, imprisoned or deported.

At the time, the federal government and the general population had narrow, and often racially defined, ideas about which immigrants were deemed desirable. Once the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in 1885 (built largely by Chinese immigrant labourers), the government barred people of “Chinese or Mongolian race” from voting, and imposed a special immigration fee — a head tax — on Chinese workers and family members coming to Canada.

In 1923, the federal government went beyond the fee-based admission policy of the head tax, and passed the Chinese Immigration Act. This effectively cut off any further immigration from China. Family members could no longer immigrate, which meant that the occasional return visit to China was the only means of reuniting families.

Chinese Canadians maintained community ties and fought for their rights through a variety of community associations. These included sports teams, such as the Chinese Students’ Soccer Team, which was a successful Vancouver team established in 1920. The 1923 Chinese Immigration Act was not abolished until 1947.

On June 22, 2006, after many years of lobbying and demands for restitution by Chinese Canadians, the federal government apologized for the Chinese head tax. Those subjected to the tax who were still alive were given compensation, as were their spouses. A group of Chinese Canadians who had paid the head tax, along with their families, travelled to Ottawa by train for the government’s official apology.

This certificate belonged to Ann Fong (1916–2016). Born in Montréal, where she lived her entire life, Ann was the youngest of five children. Her father, Fong Monking, a merchant, immigrated to Canada around 1887, and her mother, Alice Chiu, immigrated in 1893 at the age of 7. Both were from China’s Guangdong province.

Ann graduated from the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal’s Commercial High School, and worked for many years for the printing company that produced telephone books. It was here that she met her husband, Norman Stanley, who was not Chinese.

As a biracial couple, they faced intense racism when they married in 1943 and, for that reason, they at first decided not to have children. They eventually had two sons and lived to see all four of their grandchildren.

The entire Fong family had to register under the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act. The certificates for Ann’s mother and her three sisters are also displayed at the Museum.

- This is a Chinese Immigration Act This certificate belonged to Ann Fong (b. 1916; d. 2016). The youngest of five children, Ann was born in Montréal in 1916, where she lived her entire life.

- In 1885, the government barred people of “Chinese or Mongolian race” from voting and imposed a special immigration fee — a head tax — on Chinese workers and their family members coming to Canada.

- The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 required “every person of Chinese descent or origin” living in Canada, including those born in Canada, to carry a Chinese Immigration Act certificate like this one. It also cut off any further immigration from China. Family members could no longer immigrate.

- On June 22, 2006, after many years of lobbying and demands for restitution by Chinese Canadians, the federal government apologized for the Chinese head tax.

Scroll through the media carousel above to see a photo of Prime Minister Stephen Harper being presented with a ceremonial last spike by James Pon, a Chinese head tax payer, a group photo of the Chinese Students Football Club, and a photo of Lila Wong, Jean Suey Zee Lee and Marion Laura Mah at a citizenship ceremony in 1947.

This is a Chinese Immigration Act certificate. The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 required “every person of Chinese descent or origin” living in Canada, including those born in Canada, to carry a certificate like this one. Anyone who failed to produce such a certificate could be fined, imprisoned or deported.

Once the Canadian Pacific Railway was complete in 1885 (built largely by Chinese immigrant labourers), the government barred people of “Chinese or Mongolian race” from voting and imposed a special immigration fee — a head tax — on Chinese workers and their family members coming to Canada.

In 1923, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act. It effectively cut off any further immigration from China. Family members could no longer immigrate. Chinese Canadians maintained community ties and fought for their rights through a variety of community associations.

On June 22, 2006, after many years of lobbying and demands for restitution by Chinese Canadians, the federal government apologized for the Chinese head tax.

This certificate belonged to Ann Fong (b. 1916; d. 2016). The youngest of five children, Ann was born in Montréal in 1916, where she lived her entire life. Her father, Fong Monking, a merchant, immigrated to Canada around 1887 and her mother, Alice Chiu, immigrated in 1893 at the age of 7. Both were from Guangdong province in China.

This is a Chinese Immigration Act certificate. The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 required “every person of Chinese descent or origin” living in Canada — including those born in the country — to carry a certificate like this one. Anyone who failed to produce such a certificate could be fined, imprisoned or deported.

At the time, the federal government and the general population had narrow, and often racially defined, ideas about which immigrants were deemed desirable. Once the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in 1885 (built largely by Chinese immigrant labourers), the government barred people of “Chinese or Mongolian race” from voting, and imposed a special immigration fee — a head tax — on Chinese workers and family members coming to Canada.

In 1923, the federal government went beyond the fee-based admission policy of the head tax, and passed the Chinese Immigration Act. This effectively cut off any further immigration from China. Family members could no longer immigrate, which meant that the occasional return visit to China was the only means of reuniting families.

Chinese Canadians maintained community ties and fought for their rights through a variety of community associations. These included sports teams, such as the Chinese Students’ Soccer Team, which was a successful Vancouver team established in 1920. The 1923 Chinese Immigration Act was not abolished until 1947.

On June 22, 2006, after many years of lobbying and demands for restitution by Chinese Canadians, the federal government apologized for the Chinese head tax. Those subjected to the tax who were still alive were given compensation, as were their spouses. A group of Chinese Canadians who had paid the head tax, along with their families, travelled to Ottawa by train for the government’s official apology.

This certificate belonged to Ann Fong (1916–2016). Born in Montréal, where she lived her entire life, Ann was the youngest of five children. Her father, Fong Monking, a merchant, immigrated to Canada around 1887, and her mother, Alice Chiu, immigrated in 1893 at the age of 7. Both were from China’s Guangdong province.

Ann graduated from the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal’s Commercial High School, and worked for many years for the printing company that produced telephone books. It was here that she met her husband, Norman Stanley, who was not Chinese.

As a biracial couple, they faced intense racism when they married in 1943 and, for that reason, they at first decided not to have children. They eventually had two sons and lived to see all four of their grandchildren.

The entire Fong family had to register under the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act. The certificates for Ann’s mother and her three sisters are also displayed at the Museum.

Summary

- This is a Chinese Immigration Act This certificate belonged to Ann Fong (b. 1916; d. 2016). The youngest of five children, Ann was born in Montréal in 1916, where she lived her entire life.

- In 1885, the government barred people of “Chinese or Mongolian race” from voting and imposed a special immigration fee — a head tax — on Chinese workers and their family members coming to Canada.

- The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 required “every person of Chinese descent or origin” living in Canada, including those born in Canada, to carry a Chinese Immigration Act certificate like this one. It also cut off any further immigration from China. Family members could no longer immigrate.

- On June 22, 2006, after many years of lobbying and demands for restitution by Chinese Canadians, the federal government apologized for the Chinese head tax.

Scroll through the media carousel above to see a photo of Prime Minister Stephen Harper being presented with a ceremonial last spike by James Pon, a Chinese head tax payer, a group photo of the Chinese Students Football Club, and a photo of Lila Wong, Jean Suey Zee Lee and Marion Laura Mah at a citizenship ceremony in 1947.

Essential

This is a Chinese Immigration Act certificate. The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 required “every person of Chinese descent or origin” living in Canada, including those born in Canada, to carry a certificate like this one. Anyone who failed to produce such a certificate could be fined, imprisoned or deported.

Once the Canadian Pacific Railway was complete in 1885 (built largely by Chinese immigrant labourers), the government barred people of “Chinese or Mongolian race” from voting and imposed a special immigration fee — a head tax — on Chinese workers and their family members coming to Canada.

In 1923, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act. It effectively cut off any further immigration from China. Family members could no longer immigrate. Chinese Canadians maintained community ties and fought for their rights through a variety of community associations.

On June 22, 2006, after many years of lobbying and demands for restitution by Chinese Canadians, the federal government apologized for the Chinese head tax.

This certificate belonged to Ann Fong (b. 1916; d. 2016). The youngest of five children, Ann was born in Montréal in 1916, where she lived her entire life. Her father, Fong Monking, a merchant, immigrated to Canada around 1887 and her mother, Alice Chiu, immigrated in 1893 at the age of 7. Both were from Guangdong province in China.

In-Depth

This is a Chinese Immigration Act certificate. The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 required “every person of Chinese descent or origin” living in Canada — including those born in the country — to carry a certificate like this one. Anyone who failed to produce such a certificate could be fined, imprisoned or deported.

At the time, the federal government and the general population had narrow, and often racially defined, ideas about which immigrants were deemed desirable. Once the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in 1885 (built largely by Chinese immigrant labourers), the government barred people of “Chinese or Mongolian race” from voting, and imposed a special immigration fee — a head tax — on Chinese workers and family members coming to Canada.

In 1923, the federal government went beyond the fee-based admission policy of the head tax, and passed the Chinese Immigration Act. This effectively cut off any further immigration from China. Family members could no longer immigrate, which meant that the occasional return visit to China was the only means of reuniting families.

Chinese Canadians maintained community ties and fought for their rights through a variety of community associations. These included sports teams, such as the Chinese Students’ Soccer Team, which was a successful Vancouver team established in 1920. The 1923 Chinese Immigration Act was not abolished until 1947.

On June 22, 2006, after many years of lobbying and demands for restitution by Chinese Canadians, the federal government apologized for the Chinese head tax. Those subjected to the tax who were still alive were given compensation, as were their spouses. A group of Chinese Canadians who had paid the head tax, along with their families, travelled to Ottawa by train for the government’s official apology.

This certificate belonged to Ann Fong (1916–2016). Born in Montréal, where she lived her entire life, Ann was the youngest of five children. Her father, Fong Monking, a merchant, immigrated to Canada around 1887, and her mother, Alice Chiu, immigrated in 1893 at the age of 7. Both were from China’s Guangdong province.

Ann graduated from the Protestant School Board of Greater Montreal’s Commercial High School, and worked for many years for the printing company that produced telephone books. It was here that she met her husband, Norman Stanley, who was not Chinese.

As a biracial couple, they faced intense racism when they married in 1943 and, for that reason, they at first decided not to have children. They eventually had two sons and lived to see all four of their grandchildren.

The entire Fong family had to register under the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act. The certificates for Ann’s mother and her three sisters are also displayed at the Museum.