Hat

Artifact

Image

Video

Audio

Activities

Activities

LOOK

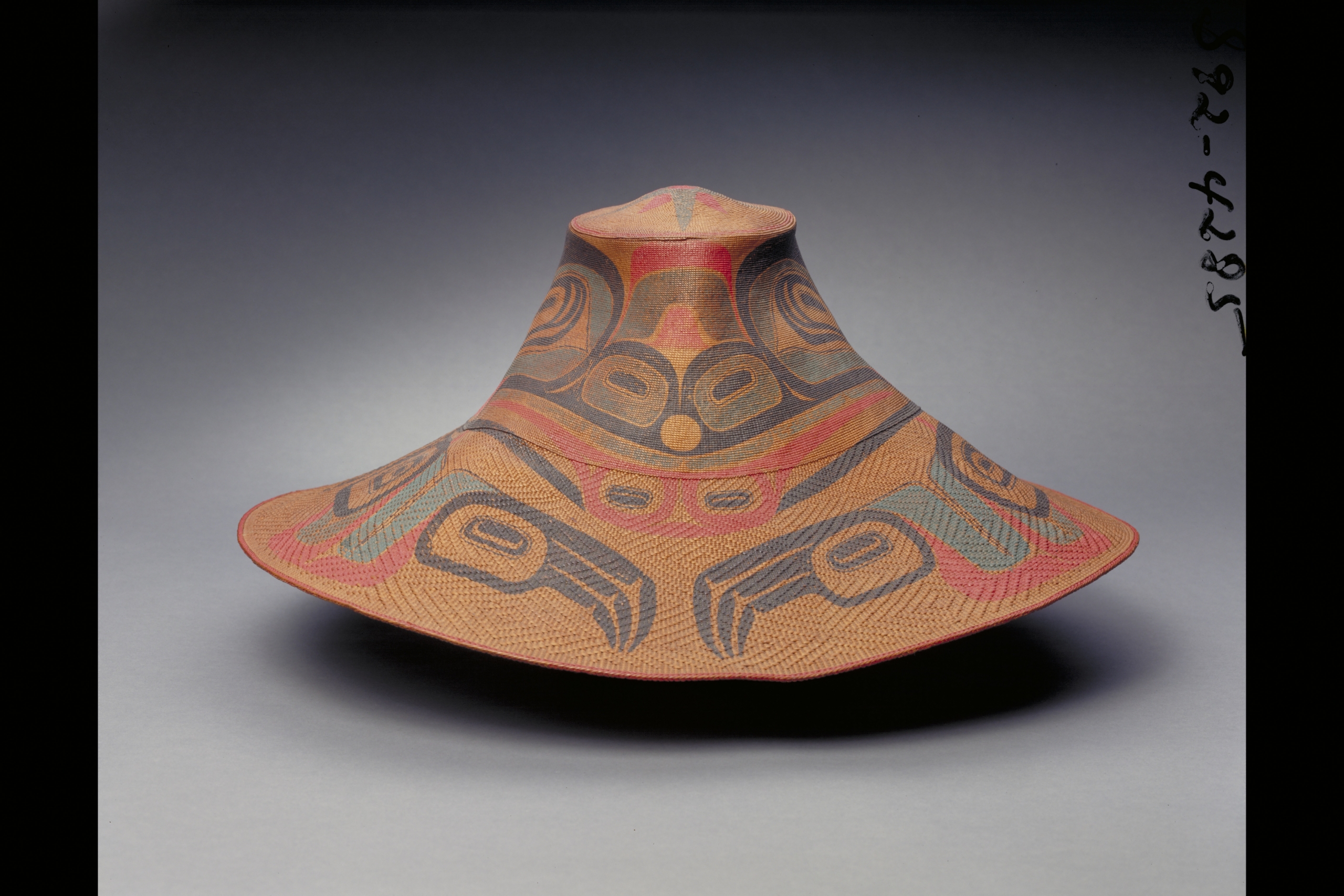

Look at this object. What do you see? What do you think it’s made of? What do you think it was used for? Read the historical context provided to verify your answers.

THINK

Look at this object and read about its historical context. Then watch the video From Spruce Roots to Baskets With a Haida Weaver that’s included in this package. How long do you think it took to weave this hat?

Answer: The precise time isn’t known, but a hat of this type would have taken at least a few months to complete. That estimate doesn’t include time spent on gathering and preparing the materials.

Details

Materials

Materials - Spruce Roots

- Mineral Paint

Historical Context

Choose one of the three levels below to match your needs.

- This dajáng (hat) was collected in the 19th century, at a time when ginn xay ‘léeygang (weavers) were making more and more hats for sale to ‘Yáats Xaadée (Euro-American) visitors and collectors due to colonial practises and the resulting devastating economic circumstances.

- This dajáng (hat) is larger than an average hlíing dajángee (spruce-root hat). There are two different weaving techniques used to make this hat, and there is a creature painted around the sides in formline style.

- Watch award-winning Haida weaver Ariane Xay Kuyaas speak more about this hat in the next video.

When this hat was collected in the late 19th century, ginn xay ‘leeygang (Haida weavers) were making fewer dajáng (hats) for household and ceremonial use due to colonial practises and the resulting devastating economic circumstances. More and more, ginn xay ‘leeygang (weavers) were making hats for sale and to trade to ‘Yáats’ X̱áadee (Euro-American) visitors and collectors in order to survive within the conditions of colonialism.

This dajáng (hat) is larger than an average hlíing dajángée (spruce-root hat) and has a very fine weave. The weaver used one weaving technique on the top of the hat, and another on the brim. The creature painted on the sides of the hat was likely done by a male artist in formline style.

Watch award-winning Haida weaver Ariane Xay Kuyaas speak more about this hat in the next video.

Ginn xay (weaving) plays a central role in the economic and social history of X̱aadgée (Haida people). Women weavers inherit the knowledge and skills required to source, gather, process and weave dajáng (hats), baskets, and other items from their áwlang (mothers), sḵáanalang (aunts) and náanalang (grandmothers).

When this hat was collected in the late 19th century, ginn xay ‘leeygang (Haida weavers) were making fewer dajáng (hats) for household and ceremonial use due to colonial practises and the resulting devastating economic circumstances. More and more, ginn xay ‘leeygang (weavers) were making hats for sale and to trade to ‘Yáats’ X̱áadee (Euro-American) visitors and collectors in order to survive within the conditions of colonialism.

This hat is larger than an average hlíing dajángée (spruce-root hat) and has a very fine weave. The weaver completed the crown of the hat with three-strand twining (a style of weaving), and at the start of the brim, changed to two-strand twining, which results in the concentric diamond dúuduuaayángaa (dragonfly) pattern. The crest design featuring a symmetric zoomorphic figure was likely painted by a male artist in formline style.

To the trained eye, a ginn xay ‘leeygaa (weaver’s) “signature” is visible in the details of her work: her personal style is discernible in the way she twines the hlíing (spruce roots) on the crown and finishes the brim. These details have been likened to “fingerprints” on the hat. Today, contemporary weavers engage with historic works such as this dajáng (hat), to learn from their teachings. In the video Exploring a Traditional Woven Haida Hat, award-winning Haida weaver Ariane Xay Kuyaas discusses this hat.

- This dajáng (hat) was collected in the 19th century, at a time when ginn xay ‘léeygang (weavers) were making more and more hats for sale to ‘Yáats Xaadée (Euro-American) visitors and collectors due to colonial practises and the resulting devastating economic circumstances.

- This dajáng (hat) is larger than an average hlíing dajángee (spruce-root hat). There are two different weaving techniques used to make this hat, and there is a creature painted around the sides in formline style.

- Watch award-winning Haida weaver Ariane Xay Kuyaas speak more about this hat in the next video.

When this hat was collected in the late 19th century, ginn xay ‘leeygang (Haida weavers) were making fewer dajáng (hats) for household and ceremonial use due to colonial practises and the resulting devastating economic circumstances. More and more, ginn xay ‘leeygang (weavers) were making hats for sale and to trade to ‘Yáats’ X̱áadee (Euro-American) visitors and collectors in order to survive within the conditions of colonialism.

This dajáng (hat) is larger than an average hlíing dajángée (spruce-root hat) and has a very fine weave. The weaver used one weaving technique on the top of the hat, and another on the brim. The creature painted on the sides of the hat was likely done by a male artist in formline style.

Watch award-winning Haida weaver Ariane Xay Kuyaas speak more about this hat in the next video.

Ginn xay (weaving) plays a central role in the economic and social history of X̱aadgée (Haida people). Women weavers inherit the knowledge and skills required to source, gather, process and weave dajáng (hats), baskets, and other items from their áwlang (mothers), sḵáanalang (aunts) and náanalang (grandmothers).

When this hat was collected in the late 19th century, ginn xay ‘leeygang (Haida weavers) were making fewer dajáng (hats) for household and ceremonial use due to colonial practises and the resulting devastating economic circumstances. More and more, ginn xay ‘leeygang (weavers) were making hats for sale and to trade to ‘Yáats’ X̱áadee (Euro-American) visitors and collectors in order to survive within the conditions of colonialism.

This hat is larger than an average hlíing dajángée (spruce-root hat) and has a very fine weave. The weaver completed the crown of the hat with three-strand twining (a style of weaving), and at the start of the brim, changed to two-strand twining, which results in the concentric diamond dúuduuaayángaa (dragonfly) pattern. The crest design featuring a symmetric zoomorphic figure was likely painted by a male artist in formline style.

To the trained eye, a ginn xay ‘leeygaa (weaver’s) “signature” is visible in the details of her work: her personal style is discernible in the way she twines the hlíing (spruce roots) on the crown and finishes the brim. These details have been likened to “fingerprints” on the hat. Today, contemporary weavers engage with historic works such as this dajáng (hat), to learn from their teachings. In the video Exploring a Traditional Woven Haida Hat, award-winning Haida weaver Ariane Xay Kuyaas discusses this hat.

Summary

- This dajáng (hat) was collected in the 19th century, at a time when ginn xay ‘léeygang (weavers) were making more and more hats for sale to ‘Yáats Xaadée (Euro-American) visitors and collectors due to colonial practises and the resulting devastating economic circumstances.

- This dajáng (hat) is larger than an average hlíing dajángee (spruce-root hat). There are two different weaving techniques used to make this hat, and there is a creature painted around the sides in formline style.

- Watch award-winning Haida weaver Ariane Xay Kuyaas speak more about this hat in the next video.

Essential

When this hat was collected in the late 19th century, ginn xay ‘leeygang (Haida weavers) were making fewer dajáng (hats) for household and ceremonial use due to colonial practises and the resulting devastating economic circumstances. More and more, ginn xay ‘leeygang (weavers) were making hats for sale and to trade to ‘Yáats’ X̱áadee (Euro-American) visitors and collectors in order to survive within the conditions of colonialism.

This dajáng (hat) is larger than an average hlíing dajángée (spruce-root hat) and has a very fine weave. The weaver used one weaving technique on the top of the hat, and another on the brim. The creature painted on the sides of the hat was likely done by a male artist in formline style.

Watch award-winning Haida weaver Ariane Xay Kuyaas speak more about this hat in the next video.

In-Depth

Ginn xay (weaving) plays a central role in the economic and social history of X̱aadgée (Haida people). Women weavers inherit the knowledge and skills required to source, gather, process and weave dajáng (hats), baskets, and other items from their áwlang (mothers), sḵáanalang (aunts) and náanalang (grandmothers).

When this hat was collected in the late 19th century, ginn xay ‘leeygang (Haida weavers) were making fewer dajáng (hats) for household and ceremonial use due to colonial practises and the resulting devastating economic circumstances. More and more, ginn xay ‘leeygang (weavers) were making hats for sale and to trade to ‘Yáats’ X̱áadee (Euro-American) visitors and collectors in order to survive within the conditions of colonialism.

This hat is larger than an average hlíing dajángée (spruce-root hat) and has a very fine weave. The weaver completed the crown of the hat with three-strand twining (a style of weaving), and at the start of the brim, changed to two-strand twining, which results in the concentric diamond dúuduuaayángaa (dragonfly) pattern. The crest design featuring a symmetric zoomorphic figure was likely painted by a male artist in formline style.

To the trained eye, a ginn xay ‘leeygaa (weaver’s) “signature” is visible in the details of her work: her personal style is discernible in the way she twines the hlíing (spruce roots) on the crown and finishes the brim. These details have been likened to “fingerprints” on the hat. Today, contemporary weavers engage with historic works such as this dajáng (hat), to learn from their teachings. In the video Exploring a Traditional Woven Haida Hat, award-winning Haida weaver Ariane Xay Kuyaas discusses this hat.