Birchtown

Artifact

Image

Video

Audio

Activities

Activities

LOOK

What is your first reaction to these objects?

THINK

Why is it important to have these objects preserved?

THINK

Describe the purpose of each item.

Details

Materials

Materials - Watercolour sketch

Historical Context

Choose one of the three levels below to match your needs.

- These objects come from the community of Birchtown.

- In 1783–1784, British promises of freedom attracted more than 1,000 African Americans to Nova Scotia. Birchtown was the largest Black Loyalist settlement.

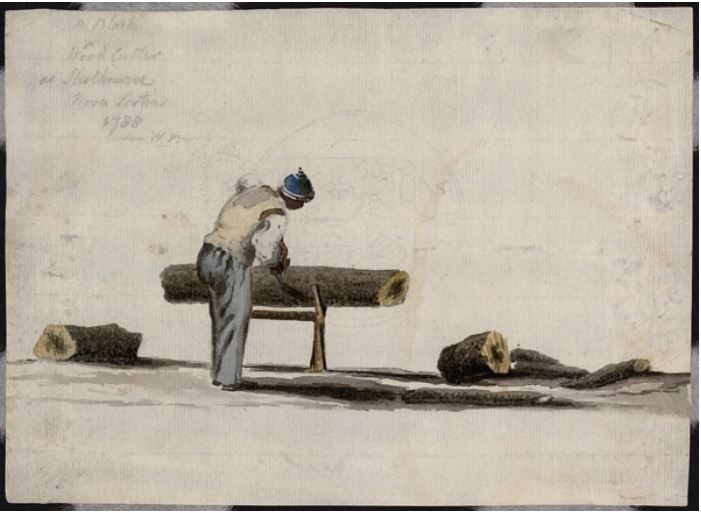

- Captain William Booth, a white officer with the Corps of Royal Engineers, painted A Black Wood Cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia in 1788.

- Black Loyalists faced poverty and racism. Within a decade, half had left for the new British colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa.

Scroll through the media carousel for more objects from Birchtown, including a pot belonging to Black Loyalist leader Colonel Stephen Blucke.

These objects come from the community of Birchtown. In 1783–1784, British promises of freedom enticed more than 1,000 African Americans to settle in Nova Scotia. Birchtown was the largest Black Loyalist settlement.

Captain William Booth, a white officer with the Corps of Royal Engineers, painted A Black Wood Cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia in 1788. Booth also wrote personal journals about life in Loyalist Nova Scotia.

The earthenware pot comes from the home of Black Loyalist leader and local schoolmaster, Colonel Stephen Blucke. The kitchen pot resembles those made in Colonial America by people of African descent.

Black Loyalists faced poverty and racism. Within a decade, half had left for the “Province of Freedom”: the new British colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa.

These two objects reflect life in the African Nova Scotian settlement of Birchtown.

Birchtown, located in Shelburne County, is usually cited as the first Black community in Nova Scotia. It was established in 1783–1784 with a population of more than 1,000 Blacks, many of whom were Loyalists promised freedom and land for supporting the British during the American War of Independence.

Although the Birchtown settlement was the largest, Black Loyalists founded communities across Nova Scotia, including Preston, Shelburne, Annapolis Royal, and Digby. The people of Birchtown earned their living through fishing, logging, clearing land, and hunting, in addition to working as domestic servants and day labourers.

This watercolour — called A Black Wood Cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia — was painted by Captain William Booth of the Corps of Royal Engineers in 1788. Although he was not Black himself, Booth’s painting offers a glimpse of what life was like for the Black Loyalists who came to Nova Scotia.

Booth was posted to Shelburne, Nova Scotia (about 7 kilometres southeast of Birchtown) between 1786 and 1789. He made numerous records of his life while stationed in Shelburne, including drawings and paintings, military and genealogical records, and personal journals. His journals are a significant primary source for life in Loyalist Nova Scotia.

The earthenware pot was found in Birchtown, at what is thought to be the site of the home of Black Loyalist leader Colonel Stephen Blucke.

In 1784, Blucke was made a lieutenant-colonel of the Shelburne District’s Black Militia by Nova Scotia’s Governor, John Parr. Blucke also became the local schoolmaster.

Made for kitchen use, this pot is similar in design and manufacture to earthenware vessels known to have been produced in colonial America by people of African descent.

Although Black Loyalists came to Nova Scotia seeking a better life, thousands ended up leaving again, in order to escape the poverty and racism they found in the settlements. In 1792, as part of a larger migration to establish a “Province of Freedom” in Sierra Leone, West Africa, 1,196 people — or approximately half of the Blacks Loyalists who had settled in the province a decade earlier — left for the new British Crown Colony.

- These objects come from the community of Birchtown.

- In 1783–1784, British promises of freedom attracted more than 1,000 African Americans to Nova Scotia. Birchtown was the largest Black Loyalist settlement.

- Captain William Booth, a white officer with the Corps of Royal Engineers, painted A Black Wood Cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia in 1788.

- Black Loyalists faced poverty and racism. Within a decade, half had left for the new British colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa.

Scroll through the media carousel for more objects from Birchtown, including a pot belonging to Black Loyalist leader Colonel Stephen Blucke.

These objects come from the community of Birchtown. In 1783–1784, British promises of freedom enticed more than 1,000 African Americans to settle in Nova Scotia. Birchtown was the largest Black Loyalist settlement.

Captain William Booth, a white officer with the Corps of Royal Engineers, painted A Black Wood Cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia in 1788. Booth also wrote personal journals about life in Loyalist Nova Scotia.

The earthenware pot comes from the home of Black Loyalist leader and local schoolmaster, Colonel Stephen Blucke. The kitchen pot resembles those made in Colonial America by people of African descent.

Black Loyalists faced poverty and racism. Within a decade, half had left for the “Province of Freedom”: the new British colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa.

These two objects reflect life in the African Nova Scotian settlement of Birchtown.

Birchtown, located in Shelburne County, is usually cited as the first Black community in Nova Scotia. It was established in 1783–1784 with a population of more than 1,000 Blacks, many of whom were Loyalists promised freedom and land for supporting the British during the American War of Independence.

Although the Birchtown settlement was the largest, Black Loyalists founded communities across Nova Scotia, including Preston, Shelburne, Annapolis Royal, and Digby. The people of Birchtown earned their living through fishing, logging, clearing land, and hunting, in addition to working as domestic servants and day labourers.

This watercolour — called A Black Wood Cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia — was painted by Captain William Booth of the Corps of Royal Engineers in 1788. Although he was not Black himself, Booth’s painting offers a glimpse of what life was like for the Black Loyalists who came to Nova Scotia.

Booth was posted to Shelburne, Nova Scotia (about 7 kilometres southeast of Birchtown) between 1786 and 1789. He made numerous records of his life while stationed in Shelburne, including drawings and paintings, military and genealogical records, and personal journals. His journals are a significant primary source for life in Loyalist Nova Scotia.

The earthenware pot was found in Birchtown, at what is thought to be the site of the home of Black Loyalist leader Colonel Stephen Blucke.

In 1784, Blucke was made a lieutenant-colonel of the Shelburne District’s Black Militia by Nova Scotia’s Governor, John Parr. Blucke also became the local schoolmaster.

Made for kitchen use, this pot is similar in design and manufacture to earthenware vessels known to have been produced in colonial America by people of African descent.

Although Black Loyalists came to Nova Scotia seeking a better life, thousands ended up leaving again, in order to escape the poverty and racism they found in the settlements. In 1792, as part of a larger migration to establish a “Province of Freedom” in Sierra Leone, West Africa, 1,196 people — or approximately half of the Blacks Loyalists who had settled in the province a decade earlier — left for the new British Crown Colony.

Summary

- These objects come from the community of Birchtown.

- In 1783–1784, British promises of freedom attracted more than 1,000 African Americans to Nova Scotia. Birchtown was the largest Black Loyalist settlement.

- Captain William Booth, a white officer with the Corps of Royal Engineers, painted A Black Wood Cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia in 1788.

- Black Loyalists faced poverty and racism. Within a decade, half had left for the new British colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa.

Scroll through the media carousel for more objects from Birchtown, including a pot belonging to Black Loyalist leader Colonel Stephen Blucke.

Essential

These objects come from the community of Birchtown. In 1783–1784, British promises of freedom enticed more than 1,000 African Americans to settle in Nova Scotia. Birchtown was the largest Black Loyalist settlement.

Captain William Booth, a white officer with the Corps of Royal Engineers, painted A Black Wood Cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia in 1788. Booth also wrote personal journals about life in Loyalist Nova Scotia.

The earthenware pot comes from the home of Black Loyalist leader and local schoolmaster, Colonel Stephen Blucke. The kitchen pot resembles those made in Colonial America by people of African descent.

Black Loyalists faced poverty and racism. Within a decade, half had left for the “Province of Freedom”: the new British colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa.

In-Depth

These two objects reflect life in the African Nova Scotian settlement of Birchtown.

Birchtown, located in Shelburne County, is usually cited as the first Black community in Nova Scotia. It was established in 1783–1784 with a population of more than 1,000 Blacks, many of whom were Loyalists promised freedom and land for supporting the British during the American War of Independence.

Although the Birchtown settlement was the largest, Black Loyalists founded communities across Nova Scotia, including Preston, Shelburne, Annapolis Royal, and Digby. The people of Birchtown earned their living through fishing, logging, clearing land, and hunting, in addition to working as domestic servants and day labourers.

This watercolour — called A Black Wood Cutter at Shelburne, Nova Scotia — was painted by Captain William Booth of the Corps of Royal Engineers in 1788. Although he was not Black himself, Booth’s painting offers a glimpse of what life was like for the Black Loyalists who came to Nova Scotia.

Booth was posted to Shelburne, Nova Scotia (about 7 kilometres southeast of Birchtown) between 1786 and 1789. He made numerous records of his life while stationed in Shelburne, including drawings and paintings, military and genealogical records, and personal journals. His journals are a significant primary source for life in Loyalist Nova Scotia.

The earthenware pot was found in Birchtown, at what is thought to be the site of the home of Black Loyalist leader Colonel Stephen Blucke.

In 1784, Blucke was made a lieutenant-colonel of the Shelburne District’s Black Militia by Nova Scotia’s Governor, John Parr. Blucke also became the local schoolmaster.

Made for kitchen use, this pot is similar in design and manufacture to earthenware vessels known to have been produced in colonial America by people of African descent.

Although Black Loyalists came to Nova Scotia seeking a better life, thousands ended up leaving again, in order to escape the poverty and racism they found in the settlements. In 1792, as part of a larger migration to establish a “Province of Freedom” in Sierra Leone, West Africa, 1,196 people — or approximately half of the Blacks Loyalists who had settled in the province a decade earlier — left for the new British Crown Colony.