The Explorers

Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

Samuel de Champlain (sometimes called Samuel Champlain in English documents) was born at Brouage, in the Saintonge province of Western France, about 1570. He wrote in 1613 that he acquired an interest “from a very young age in the art of navigation, along with a love of the high seas.” He was not yet twenty when he made his first voyage, to Spain and from there to the West Indies and South America. He visited Porto Rico (now Puerto Rico,) Mexico, Colombia, the Bermudas and Panama. Between 1603 and 1635, he made 12 stays in North America. He was an indefatigable explorer – and an assistant to other explorers – in the quest for an overland route across America to the Pacific, and onwards to the riches of the Orient.

The Mystery of Samuel de Champlain

In the title of his first book, published in 1603, Des Sauvages, ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouage, fait en la France nouvelle l’an mil six cens trois… [“Concerning the Primitives: Or Travels of Samuel Champlain of Brouage, Made in New France in the Year 1603”], Samuel de Champlain indicated that he was a native of Brouage in the Saintonge region of France. But a fire in the 17th century completely destroyed the town records of Brouage, where the young Champlain was believed to have spent his childhood. Since then, historians have speculated about the birth date of the man often described as the “Father of New France.”

The name “Samuel,” taken from the Old Testament, suggests the possibility that Champlain was born into a Protestant family during a period when France was torn by endless conflicts over religion. However, by the time he undertook his voyages of discovery and exploration to Canada, he had definitely converted to Catholicism. The marriage contract between Samuel de Champlain and Hélène Boullé, dated 1610, shows that he was the son of the then-deceased sea captain, Anthoine de Champlain, and Marguerite Le Roy. On this basis, several historians have deduced that Champlain must have been born around 1570.

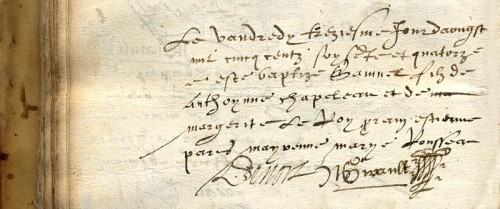

These are the few facts that history reveals, leaving room for all sorts of hypotheses about Champlain’s date of birth. But things were to take a different turn in the spring of 2012 when Jean-Marie Germe, a French genealogist, was examining the archives of the Protestant parish of Saint Yon de La Rochelle. In Champlain’s time, La Rochelle was a neighbouring town and rival of Brouage. What Mr. Germe found there was the baptismal record of Samuel Chapeleau, son of Antoine Chapeleau and Marguerite Le Roy, dated August 13, 1574.

Is this the baptismal certificate of the “Father of New France”? Certainly the document is difficult to read; the letters often have to be deciphered as much from their context, as from their appearance. Moreover, in that era the rules of spelling were flexible, to say the least. The different spellings used for the family name of the child and his father can be explained by the fact these names had perhaps previously been written down only rarely. A standard spelling had possibly not yet been adopted.

What are the chances of finding another baptismal certificate dating from this era where the names are identical to those we find in other historical documents? The chances are in fact very small indeed. However, even though the family names of Chapeleau and Champlain are similar, this small difference — understandable as it may be — cautions us not to jump to conclusions. Although the probability is slight, it is still possible that this document has nothing to do with our Samuel de Champlain.

If we are indeed looking at the baptismal certificate of our Samuel de Champlain, we can now say for certain that he was born into a Protestant family, most probably during the summer of 1574. But unless there is another discovery to equal the one made by Mr. Germe, a complete mystery will continue to surround Samuel de Champlain’s date and place of birth.

“On Friday, the thirteenth day of August, fifteen hundred and seventy-four, Samuel, son of Antoine Chapeleau and of m [word crossed out] Marguerite Le Roy, was baptized. Godfather, Étienne Paris; godmother, Marie Rousseau. Denors N. Girault.”

In the Footsteps of Jacques Cartier

In 1602 or thereabouts, Henry IV of France appointed Champlain as hydrographer royal. Aymar de Chaste, governor of Dieppe in Northern France, had obtained a monopoly of the fur trade and set up a trading post at Tadoussac. He invited Champlain to join an expedition he was sending there. Champlain’s mission was clear; it was to explore the country called New France, examine its waterways and then choose a site for a large trading factory.

Thus Champlain sailed from Honfleur on the fifteenth of March, 1603, and prepared to follow the route that Jacques Cartier had opened up in 1535. He proceeded to explore part of the valley of the Saguenay river and was led to suspect the existence of Hudson Bay. He then sailed up the St. Lawrence as far as Hochelaga (the site of Montreal.) Nothing was to be seen of the Amerindian people and village which Cartier had visited, and Sault St. Louis (the Lachine Rapids) still seemed impassable. However, Champlain learned from his guides that above the rapids there were three great lakes (Erie, Huron and Ontario) to be explored.

Acadia and the Atlantic Coast

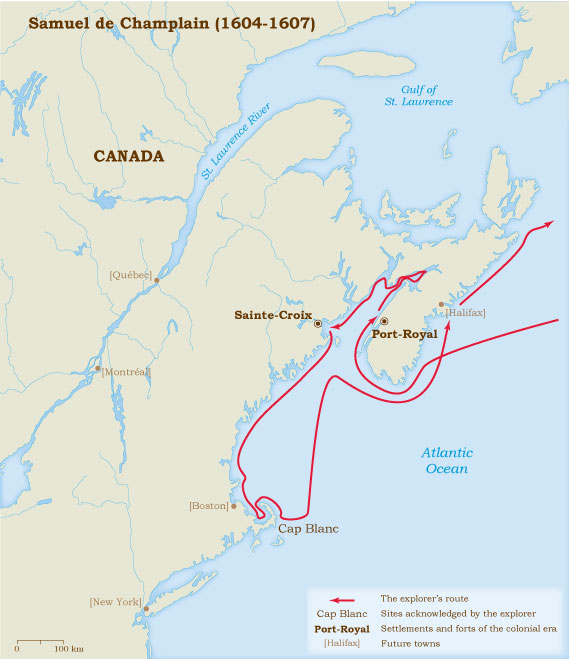

After Aymar de Chaste died in France in 1603, Pierre Du Gua de Monts became lieutenant-general of Acadia. In exchange for a ten years exclusive trading patent, de Monts undertook to settle sixty homesteaders a year in that part of New France. From 1604 to 1607, the search went on for a suitable permanent site for them. It led to the establishment of a short-lived settlement at Port Royal (Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia.)

While the settlers were tilling, building, hunting and fishing, Champlain carried on with his appointed task of investigating the coastline and looking for safe harbours.

Routes

The three years stay in Acadia allowed him plenty of time for exploration, description and map-making. He journeyed almost 1,500 kilometres along the Atlantic coast from Maine as far as southernmost Cape Cod.

From Quebec to Lake Champlain

In 1608, Champlain proposed a return to the valley of the St. Lawrence, specifically to Stadacona, which he called Quebec. In his opinion, nowhere else was so suitable for the fur trade and as a starting point from which to search for the elusive route to China. During this third voyage he learned of the existence of Lac Saint Jean (Lake St. John), and on the third of July, 1608, he founded what was to become Quebec City. He immediately set about building his Habitation (residence) there.

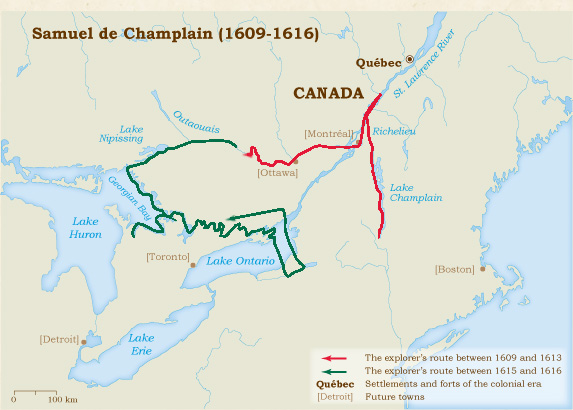

Champlain also explored the Iroquois River (now called the Richelieu), which led him on the fourteenth of July, 1609, to the lake which would later bear his name. Like the traders who had preceded him, he sided with the Hurons, Algonquins and Montaignais against the Iroquois. This intervention in local politics was ultimately responsible for the warlike relations that were to pit the Iroquois against the French for generations.

From the Ottawa Valley to Lake Huron

In 1611, Champlain returned to the area of the Hochelaga islands. He found an ideal harbour, and facing it he built the Place Royale (royal square), around which the town would later develop from 1642 onwards.

Even more important, he succeeded in penetrating beyond the Lachine Rapids, becoming the first European (apart from Étienne Brûlé) to start exploring the St. Lawrence and its tributaries as a route towards the interior of the continent. Champlain was so convinced that it was the route to the Orient that in 1612 he obtained a commission to “search for a free passage by which to reach the country called China.” Like most of the explorers who followed after him, he could not carry out his mission without the support of the Amerindian population.

The following year Champlain was induced to make a voyage up the Ottawa River in the course of which he reached Allumette Island. It was his initial foray along the route that was to lead him to the heartland of present-day Ontario and eventually to reach Lake Huron on the first of August, 1615.

Routes

That was to be Champlain’s last voyage of exploration. In the years that followed, he devoted all his efforts to founding a French colony in the St. Lawrence valley. The keystone of his project was the settlement at Quebec.

When it capitulated to the English Kirke brothers in 1629, Champlain returned to France, where he lobbied incessantly for the cause of New France. He finally returned to Canada on the twenty-second of May, 1633. At the time of his death at Quebec on the twenty-fifth of December, 1635, there were one hundred and fifty French men and women living in the colony.