The Explorers

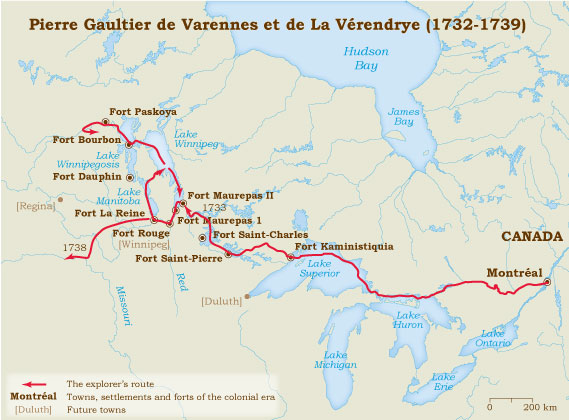

Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye was born in Trois-Rivières on November 17, 1685. The last of the nine children of René Gaultier de Varennes, a former officer of the Carignan Regiment, and Marie Boucher, he was the grandson of Pierre Boucher. At an age when others were enjoying their retirement, he was exploring the Canadian West and having eight forts or trading posts built between Lake Superior and present-day Manitoba. Two of his sons were the first Frenchmen to see and describe the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains.

Route

Soldier and Farmer

At the age of 11, Pierre Gauthier de Varennes was enrolled in the Jesuit seminary in Québec. Three years later, after completing part of the secondary course, he joined the army. In 1704 and 1705, first as a cadet and then an ensign, he took part in the armed struggle between France and England in New England and Newfoundland. Anxious to rise in the military ranks, he went to France where he joined the Brittany regiment. In 1709, the War of the Spanish Succession brought him a few injuries, imprisonment and the rank of lieutenant. Upon the death of his brother Louis, a sub-lieutenant in the same regiment, Pierre adopted the appellation by which Louis had been known: La Vérendrye.

He was granted permission to return to New France on May 24, 1712. In the fall he married Marie-Anne Dandonneau du Sablé, the fiancée who had been waiting for him for five years. They settled in the Trois-Rivières area, where farming became their main source of income.

The Search for the “Vermilion Sea”

By 1726 Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye was the head of a family of four boys and two girls. He then turned away from his hitherto sedentary life to join the fur trading venture formed by his brother Jacques-René, commandant of the Poste du Nord in the Lake Superior region. Upon arrival there, he accepted the post of second in command, later becoming commandant in 1728.

During these two years in the northern posts of the Great Lakes Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye became certain that exploration of Lake Winnipeg and the “great Western river” would ultimately lead to the discovery of the Pacific Ocean.

In 1728 and 1729, he applied to the governor Charles de Beauharnois to set out for the West on an official mission, arguing that he already knew the route and had a knowledgeable guide: “I have also taken care to acquire a Savage capable of leading there a convoy, in the event that it should please His Majesty to honour me with your orders to effect this Discovery.”

He pleaded his case in person in Québec, in 1730. The governor and Intendant Gilles Hocquart supported the project as if it were their own. They defended it to the minister of the colonies, emphasizing the fact that a French presence in the West would enrich New France while at the same time damaging British trade in Hudson Bay.

First Forts on the Prairie Frontier

When he left Montreal on June 8, 1731, in the company of three of his sons and some 50 engagés, La Vérendrye had no financial backing. He had eight partners with whom he shared the fur trade monopoly in the Lake Winnipeg region.

In late August, the group passed Michillimakinac and Lake Superior. Despite the defection of some engagés, part of the expedition, headed by La Vérendrye’s son and nephew, headed for Rainy Lake. Fort Saint-Pierre was already constructed before the onset of winter. In the early summer of 1732, there were at Lake of the Woods, where Fort Saint-Charles was built. The following year a secondary post was established on the Red River. In May 1734, while La Vérendrye was en route to Montreal, he had some men march to Lake Winnipeg where they commenced construction of Fort Maurepas, named after the minister of the colonies.

The Beaver Sea

Given what was expected of him, the fact that La Vérendrye had dispatched large quantities of furs to the colony did not weigh heavily in his favour. He had promised to discover the Western sea, and in three years had gone no further than Lake Winnipeg. Upon arriving in Québec in 1734, he found that his reputation had been tarnished by those who, paraphrasing Maurepas, said that he was “seeking not the Western sea, but the Beaver sea.”

When he set out again in June 1735, the explorer was virtually an employee of his associates. He undertook to devote himself solely to the search for the Pacific, and they would supervise the administration of the forts he built. Shortly after his arrival at Fort Saint-Charles, Christophe Dufrost de la Jemmerais, his nephew and the most efficient of his companions, succumbed to an illness. On June 6, 1736, his son Jean-Baptiste, the Jesuit Jean-Pierre Aulneau and 19 companions were murdered at Lake of the Woods.

Discovery of the Rockies

In greater debt than ever before, the explorer had to continue on. On September 28, 1738, he reached the mouth of the Assiniboine River and the site of present-day Winnipeg. He had Fort La Reine (Portage-la-Prairie, Manitoba) built in early October. On December 3 he entered what is now North Dakota. This was to be the farthest point of his travels.

After wintering at Fort La Reine, La Vérendrye returned to Montreal. Meanwhile his sons were exploring part of the Saskatchewan River and lakes Manitoba, Winnipegosis, Bourbon and Dauphin. Back in the west in the fall of 1741, La Vérendrye planned the construction of forts on lakes Bourbon and Dauphin.

On April 9, 1742, Louis-Joseph and François left Fort La Reine, with orders to travel as far as possible to the west. By January 1, 1743, they had ascended the Upper Missouri as far as Yellowstone River. A huge wall of stone barred their way and the view of the West. They were at the foot of the Rocky Mountains.

Disgrace and Envy

In 1743 Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye left the West, not knowing that he would never come back. Shortly after his return, he resigned: France ascribed no importance to the discoveries made by his family, nor to goods they yielded.

Beauharnois, who had always supported him, made his life easier by awarding him a few honorary duties in 1744. Five years later, the governor was so successful in pleading the explorer’s case that the king recognized the value of his discoveries by assigning him the management of the Western posts and awarding him the Croix de Saint-Louis, the most prestigious distinction of the time.

Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye was preparing an expedition to the Saskatchewan River when he died in Montreal on December 5, 1749. His sons benefited in no way from what they had accomplished. “Here more than elsewhere, envy remains a passion much in fashion, from which it is not possible to protect oneself,” ,” wrote Louis-Joseph to Maurepas in 1750. “Even as my father with my brothers and myself was wearing himself out with fatigue and expenditure, his efforts were represented as directed only toward the discovery of beaver, his forced expenditures as nothing but dissipation, his communications as nothing but lies. Envy in this country does not exist in half-measures […]“