The Explorers

Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

Pierre-Esprit Radisson was born around 1640, either in Avignon or Paris. No one knows when he first came to New France. In 1646, he is likely in Trois-Rivières, attending the wedding of his half-sister, Marguerite Hayet, to Jean Veron, sieur de Grandmesnil. Later, when she marries again, this time to Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers, on August 24, 1653, Radisson is living with the Iroquois who had kidnapped him and taken him to somewhere around Corlaer (Shenectady).

Even though he will later say that he was well treated during his captivity, Radisson escapes. He is recaptured near Trois-Rivières, subdued and tortured. Escaping a second time, he takes refuge at Fort Orange where he works for the Dutch as an interpreter. In 1654, he can be found in Amsterdam and, by late spring, he is back in Trois-Rivières. On July 29, 1657, he takes part in an expedition to help the Jesuit mission at Onondaga. The following year, when the mission is threatened with destruction, he organizes the evacuation of all the residents. He has just made his first mark on history.

Route

In the footsteps of Chouart Des Groseilliers

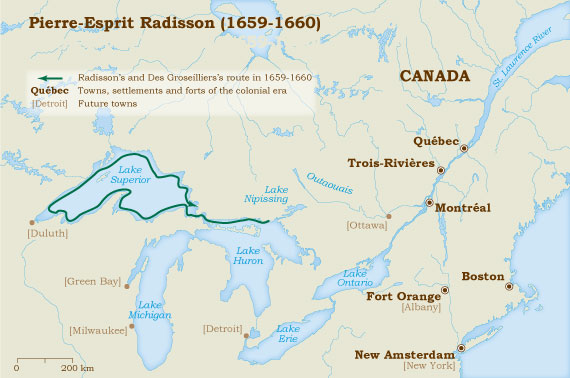

Unlike his brother-in-law, Médard Chouart des Groseilliers, Pierre-Esprit Radisson had never seen the Great Lakes nor did he seem much suited to exploration. But he had lived in the woods and had enough scars by the age of 18 or 19 to convince Des Groseilliers of his bravery. Des Groseilliers hires him and in August 1658 or 1659, they undertake their first journey together. This year-long trip takes them west of Lake Superior where Des Groseilliers knows fine-quality furs can be found.

Their stay among the Cree and their meetings with other Amerindian tribes leads them to understand that the “salt sea” that their hosts talk describe, is Hudson’s Bay. They return from their journey, convinced that the Bay can be reached by way of the Atlantic Ocean. Radisson writes, “We finally reached Québec ; (August 24, 1660) we were greeted by several cannon salvos from the fort’s battery and from some ships anchored in the harbour. These ships would have returned to France empty if we had not shown up.” Unfortunately, their furs are seized and they are fined for having left the colony without first obtaining permission from the governor, Pierre Voyer d’Argenson.

An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth

The Governor’s actions against two men whom he had so recently honoured, is not without consequences as is the failure of the Minister for the Colonies to grant reparations sought by Des Groseilliers in 1661. The following year, the two brothers-in-law go to Boston. After obtaining financing from some merchants, they attempt, unsuccessfully, to reach Hudson’s Bay. In August 1665, they set sail for London. They know that England will proved the support France refuses to supply.

Their first journey takes place in 1669. The ship carrying Radisson, The Eaglet, suffers heavy storm damage somewhere between Ireland and North America. Des Groseilliers’ ship, the Nonsuch, reaches the Nemiscau (Rupert) River where Fort Charles is located. The following year the explorer returns to England with a shipload of furs. The Hudson’s Bay Company starts to take shape. Created on May 2, 1670, the Company has three goals: fur trade, mineral exploration and finding a passage to the West.

Turn-about

Within a few weeks of the founding of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Radisson can be found sailing on the salt sea towards the mouth of the Nelson river. The next four years are made up of many comings and goings between England and the Bay. In London, near the end of 1674, Radisson and his brother-in-law meet a Frenchman who had been captured and brought to the Rupert River: Charles Albanel, a Jesuit priest. He persuades them to return to the bosom of France. The reasons for this turnabout are unclear but it seems, having told the Company everything they know, they are no long of any value to the Company.

In France, the pair are ordered back to Canada and told to come to an agreement with the authorities on how to ensure the French flag will once again fly over Hudson’s Bay. After being coldly received by Governor Frontenac, who is more interested in explorations being carried out around the Great Lakes and the Mississippi, the adventurers decide it is time for another change in direction. Des Groseilliers settles in Trois-Rivières and Radisson returns to France where he joins the Navy. Around 1680, after expeditions that took him to the coasts of Africa and the Antilles, he resigns.

A torn man

Radisson is torn. Both France and her colony are deaf to his plans for retaking Hudson’s Bay and he is far away from his wife, the daughter of Sir John Kirke, one of the partners in the Hudson’s Bay Company. The fact that she did not follow him in 1675, leads the French to believe that Radisson can still cross the Channel at will. He has to go and get her. In 1681, he travels to London. However, out of respect for her father’s wishes, Radisson’s wife refuses to leave the country.

Back in France, Radisson sees Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye whom he had met two years earlier and whom he had persuaded to take an interest in Hudson’s Bay. Aubert de La Chesnaye is eager to start up the Compagnie du Nord or the Compagnie française de la baie d’Hudson which will allow him and his business partners to control the fur trade around Hudson’s Bay. In August 1682, Radisson and Des Groseilliers lead two Company ships to the Monsoni (Hayes) River, at the southern tip of James Bay. They snatch Fort Nelson from the English, seize a ship from Boston and return with an impressive cargo of furs. When they are not paid fairly for their contribution to the mission, the two men finally call it quits. Des Groseilliers fades into obscurity. Radisson heads for France and, from there, to England.

At war with France

Back in England in early May 1684, Radisson signs on again with the Hudson’s Bay Company. Two weeks later, he sails for Hudson’s Bay. The Happy Return drops anchor near Port Nelson which soon is no longer in French hands. He travels to the Hayes River where he persuades his nephew, Médard Chouart, and the Assiniboines to support England. He empties the storehouses, taking with him the furs which belong to the French.

In 1686, New France entrusted the chevalier Pierre de Troyes with responsibility for retaking the forts around Hudson’s Bay and capturing Pierre-Esprit Radisson who was staying there at that time. In March of the following year, Louis XIV sends the colony’s administrators a message that showed that France finally recognized “the damage that this Radisson has done to the colony and the further harm he is likely to cause if he stays among the English[…] “. Having become a citizen of England in 1687, Radisson died in 1710, almost destitute. He had married three times and had had at least nine children.

History has judged Pierre-Esprit Radisson very harshly. He was never forgiven for leading England to the territories north of New France which helped weaken France’s position in North America.