The Explorers

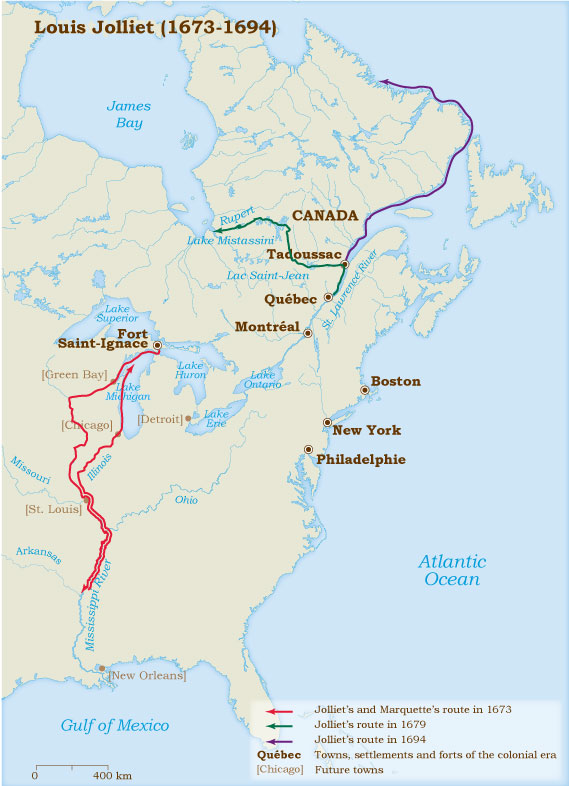

Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

Louis Jolliet (or Joliet) was born near Quebec, where he was christened on the twenty-first of September, 1645. He was the son of Jean Jolliet, a wagon-maker in the service of the Company of One Hundred Associates (Company of New France), and of Marie d’Abancourt. He was enrolled in the Jesuit college at Quebec at the age of ten and studied for the priesthood. However, he renounced his clerical vocation in 1667.

He was the first important explorer born on Canadian soil, and played a very important part in the opening-up of North America.

Route

The Lure of the Fur Trade

Louis Jolliet was twenty-three years old when he decided on the career he wished to pursue. He would become a coureur des bois (coureur de bois, wood-runner, or bush-loper, to the English,) a calling in which he was to quickly make a name for himself. On the ninth of October, 1668, he fitted himself out with trade goods from the merchant Charles Aubert de la Chesnaye: “two guns, two pistols, six packets of rassades [glass beads], twenty-four axes, a gross of small bells, twelve ells of Iroquois-style cloth, ten ells of linens, forty pounds of tobacco…” The money to buy this merchandise had been lent to him by Monsignor Laval, Bishop of Quebec, and the loan had been guaranteed the previous day by his mother. However, he actually bought the goods for his brother, Adrien Jolliet, who left with them. Hence Adrien is the “Jolliet” whom we hear of as being in the Great Lakes area during the ensuing months.

Louis Jolliet was nevertheless at Sault Ste. Marie on the fourth of June, 1671, when Simon Daumont de Saint-Lusson took formal possession of the lands of the western interior for France. Fourteen Amerindian nations attended this event, which extended the realm of Louis XIV over a territory including “this place Sainte Marie du Saut, as also Lakes Huron and Superior, the Island of Caienton [Manatoulin], and all the countries, rivers and lakes contiguous and adjacent thereunto, both those which have been discovered and those which may be discovered hereafter, bounded on the one side by the seas of the North [Hudson Bay] and of the West [the Pacific], and on the other by the South Sea [Gulf of Mexico], in all their length and breadth.” Louis Jolliet was one of the signatories of the declaration.

Jacques Marquette’s Project

A meeting between Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet no doubt took place in the Jesuit mission at Sault Ste. Marie. People at that place were well aware of the existence of the Mississipi, and Marquette planned to journey there. Jolliet was to turn this plan into a reality.

The coureur de bois was back in Quebec by September, 1671. The following year, just before his final departure for France, the great intendant Jean Talon threw his support behind the project to explore the Mississipi and persuaded the governor of the colony, Frontenac, to approve it. However, the French state put no funding into the expedition, the purpose of which was to determine whether the great river of the West really flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, and whether, by following one of its tributaries, it might be possible to reach China.

Jolliet now had to get organized. He recruited six other coureurs de bois and entered into a formal partnership with them on the first of October, 1672. They left Quebec a few days later, heading for the St. Ignace (St. Ignatius) mission at Michillimakinac, where they arrived on the eighth of December.

Journey towards the Mouth of the Mississippi

The journey by canoe to the Mississippi began in mid-May, 1673. One month later, the Mississipi unfurled before the canoeists. Turning southward, they paddled downstream until they reached the area that is today the boundary between Louisiana and Arkansas. In the middle of July, fearing “to deliver themselves to the Spaniards of Florida if they advanced further,” Jolliet and Marquette resolved to return the way they had come. They were disappointed not to have reached the mouth of the river, but they had established that the Mississippi did indeed discharge its waters into the Gulf of Mexico. They noted the existence of other rivers flowing westwards, clinging to the belief that they flowed into the Sea of Japan or the China Sea.

Returning to the colony at the end of the summer of 1674, Jolliet’s canoe was upset in the Lachine Rapids. He lost his diary and the map he had drawn during the expedition, yet he managed to recompose both of them from memory. “I was rescued after four hours in the water, by fishermen who never usually went to that spot, and who would not have been there if the Holy Virgin had not accorded me that favour… Nothing remains to me but my life.”

North Shore Seigneur and Trader

In 1675, Louis Jolliet returned to an apparently more sedentary life. He married Claire-Françoise Bissot, played the organ in the cathedral at Quebec, and became an influential personality in the colony. The truth was, however, that his interest in the fur trade had not diminished. In 1676, he made a vain request for royal permission to go and set up a trading station in the country of the Illinois. That same year he formed a company to conduct the fur trade on the North Shore of the St. Lawrence. Three years later he received a grant of the Mingan Archipelago in the lower St. Lawrence; the harvesting of its rich wildlife enabled him to assume the title of merchant in addition to those of explorer and seigneur. Anticosti Island was added to his possessions in March, 1680. He was to spend all his summers there with his family.

Overland to Hudson Bay

The officials of the French colony were worried by the English presence around Hudson Bay and the extent of their commerce with the aboriginal peoples there. So in 1679 they commissioned Jolliet to travel overland to Hudson Bay and reconnoitre the situation. Jolliet and seven companions left Quebec on the thirteenth of April. They travelled by way of the Saguenay as far as Lac Saint Jean (Lake St. John) and thence by Lake Mistassini and the Rupert River until they reached Rupert Bay (James Bay.) The English tried to induce Jolliet to join them, but he declined, and returned to Quebec convinced that Hudson Bay was the richest source of furs in the whole country and that the Englishmen’s control over it would make them masters of “all the trade of Canada.”

The Mapmaker

By about 1690, Louis Jolliet was famous not only in New France but also in France itself and even in England. Already in 1679, Charles Bayly, Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, had congratulated him for the part he had played in the Mississippi expedition, which Bayley seemed to know all about . Four years earlier, Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin had drawn his map of Jolliet’s discoveries, based on information provided by Jolliet himself and by Marquette, which was published in Paris by Estienne Michallet in 1681 under the title Voyage et découverte de quelques pays et nations de l’Amérique septentrionale. In 1685, a map of the St. Lawrence river and gulf drawn by Jolliet himself was despatched to the Ministry of the Colonies. The Seigneur of the Mingan Islands and Anticosti was still continuing in his work as explorer and mapmaker.

Description of The Labrador Coastline

In the spring of 1694, Louis Jolliet undertook a sponsored voyage of exploration, mapmaking, fishing and trading in the Labrador area. The expedition was funded by the merchant François Viennay-Pachot. Eighteen men left Quebec on the twenty-eighth of April aboard an armed vessel. They sailed past Mingan, through the Strait of Belle Isle and Baie des Esquimaux (Eskimo Bay) and up as far as the fifty-sixth parallel (Zoar). At that point, as summer was approaching its end, and “seeing no place where we might immediately find savages whose trade might defray the daily costs incurred by our vessel , we resolved by common consent to seek harbour, and there to prepare the ship for the return voyage to Quebec.”

It was the first time in the annals of North America that an explorer returned from an expedition along the Labrador coast with a detailed journal, embellished furthermore by descriptive sketches and notes on the peoples he had encountered there.

On the 13th of April, 1697, Jolliet was appointed professor of hydrography at the College of Quebec. He died some time between May and October, 1700, possibly at one of the two seigneuries he possessed on the North Shore.