The Explorers

Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

The reputation of the missionary and explorer Louis Hennepin is very bad indeed. A companion and protégé of Robert Cavelier de La Salle, who despised the Jesuits and surrounded himself with the Récollets, Hennepin followed the explorer from 1676 to 1680. He was not highly thought of in the colony where he lived for a few months at the beginning and end of his sojourn, but he painted a portrait of himself as a daring and courageous missionary.

An exceptional promoter of the territories of North America in Europe, he lied in describing himself as La Salle’s equal in the 1678 expedition to the Baie des Puants (Green Bay). Worse still, after the death of his leader, he actually claimed to have discovered the mouth of the Mississippi two years before La Salle. By claiming for himself a merit that is still disputed to this day, the author of the first description of Niagara Falls threw discredit on his own contributions to the exploration of North America.

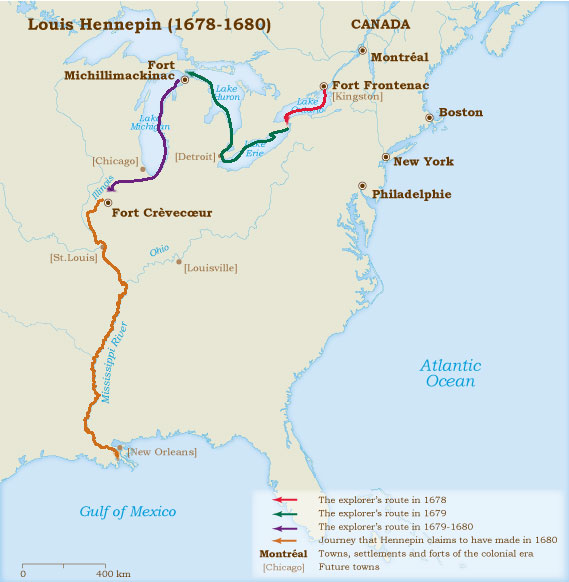

Route

The Military Chaplain

Louis Hennepin was born in Ath, Belgium, on May 12, 1626, to a family which, without being rich, nonetheless allowed him to pursue his studies. These ended in 1643 with his entrance into the order of Franciscan Récollets. Years of apostolate in Italy, Germany and Holland were followed by a stint on the French Atlantic coast, where he collected for his order. ” My greatest passion,” he wrote, concerning his stay in Calais, “was to hear the stories ships’ captains told of their long voyages […]I would have spent entire days and nights without sleeping, listening to them, because I always learned something new.”

Plunged back into the ” regulations of pure and severe virtue “, he travelled in Holland where he was caught in the midst of the Franco-Dutch war that began in 1672. As chaplain among the injured and ill soldiers, he showed true devotion. At the battle of August 11, 1674 in Seneffe, Belgium, he encountered Daniel Greysolon Dulhut who would come to his rescue in July 1680.

A Dream of Adventure

In 1675, there was no shortage of new lands to discover. Designated by his superiors along with four of his fellow priests for missions in New France, Hennepin arrived in Quebec City on June 16. The journey enabled him to meet Monseigneur de Laval and Robert Cavelier de La Salle who was returning from Versailles with titles of nobility and full ownership of the fort and the seigneurie of Cataracoui created for him.

We don’t know at exactly what moment the alliance between the missionary and La Salle the explorer was sealed, but it seems it was already settled that Hennepin would be part of the next expedition. While awaiting adventure, he performed his religious duties in the posts and missions of the North Shore, from Pointe-Claire (Montreal) to Cap-Tourmente (Beaupré).

Towards Niagara

In early spring 1676, Hennepin was sent to Fort Cataracoui, renamed Frontenac in honour of the governor. There he built a chapel and a residence for the missionaries. Two years later, he was back in Quebec City. He met Cavelier de La Salle, back from France in September 1678 with the authorization to further explore as far as Florida and New Mexico. The explorer had also obtained permission for Hennepin and two of his colleagues to come along and perform their duties in the wake of the discoveries.

Hennepin and a party of La Salle’s men left Quebec City on November 18, 1678. They were joined by the explorer at Fort Frontenac, and the group travelled to the junction of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, marked by the incredible cataract of Niagara Falls. Arriving there in the first days of December 1678, the group began the construction of Fort Conti and of a brig, the Griffon. La Salle reserved Hennepin the honour of “setting the first peg in the vessel.”

On the Great Lakes

The first ship ever to navigate on Lakes Erie, Huron and Michigan set sail on August 7, 1679. After a stop at Sault Sainte-Marie, at the junction of Lake Huron and Lake Superior, the brig headed toward Michillimakinac and Lake Michigan. At the end of the fall, it stationed in Baie des Puants (Green Bay) before being sent towards Niagara: “against our wishes,” wrote Hennepin, “Sieur de la Salle, who never took advice from anyone, resolved to send the ship on and continue the route by canoe.”

Things were going badly at Fort Crèvecoeur, built in January 1680, on the site of the present-day city of Peoria, Illinois. Workers and coureurs des bois had deserted, food was scarce and they were lacking the necessary materials for navigation. This was the context in which Cavelier de La Salle decided to return to Niagara. Hennepin apparently refused to give up, and even proposed to set out ahead on the Mississippi : “In this extreme situation, we both took a decision that was both extraordinary and difficult: myself to head out with two men into unknown territory, and La Salle to return on foot to Fort Frontenac, more than five hundred leagues away.” The two men would never see each other again.

At the Source of the Mississippi

Two coureurs des bois, Michel Accault and Antoine Auguel dit Le Picard Du Guay, accompanied Hennepin. In Description de la Louisiane nouvellement découverte au Sud Ouest de la Nouvelle-France […] published in Paris in 1683, Hennepin is clear that he did not discover the mouth of the Mississippi: “We had plans to travel to the mouth of the Colbert (Meschasipi), but the nations did not give us the time to navigate up and down this river.”

If the missionary’s tale is to be believed, between February 29 and March 10, the three men affronted the ice and travelled down the Illinois River as far as the Mississippi. From there, remounting the tumultuous river, they passed present-day Minneapolis where a waterfall was named St. Anthony Falls. Advancing toward the north and west of Lake Superior, the three men reached Lac des Issatis (Leech Lake), source of the Mississippi River.

Again according to the 1683 story, Hennepin and his companions then returned toward Fort Crèvecoeur. They were still a good distance from the mouth of the Illinois when, in the early afternoon of April 11, 1680, they were captured by the Sioux who took them toward the Mille Lacs region, south of Lake Superior. Adopted by the village chief, the three men were confined there. On July 25 Daniel Greysolon Dulhut,who had negotiated the alliance of the French and the Western tribes against the Iroquois, came to demand the liberation of Hennepin, Accault and Auguel, who were only freed in September.

A Strange Silence

After wintering in Michillimakinac, Dulhut and Hennepin returned to the colony. Curiously, the missionary, who then travelled from Montreal to Quebec City with Frontenac, told him of his expedition, but kept silent on the details of his purported voyage toward the south of the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico. He maintained the same silence with Monseigneur de Laval. On his return to France at the end of 1681, Hennepin began writing his first book. His Description de la Louisiane […] is inspired by the tales of one of his colleagues, who took part in Cavelier de La Salle’s possession of Louisiana on April 9, 1682. Dedicated to Louis XIV, the work was an enormous success. It was translated and re-edited in its original form on three occasions.

The Secret Plans of La Salle

In 1697, Louis Hennepin placed himself under the protection of the King of England, William III, to whom he dedicated the Nouvelle Découverte d’un très grand Pays Situé dans l’Amérique […], published in Utrecht, Holland. La Salle, assassinated ten years earlier, was no longer there to contradict Hennepin who for the first time evoked the misunderstanding that he claimed characterized their relations. Nor could La Salle expose the absurdity of his claim to have travelled the length of the Mississippi, in only thirty days before being captured by the Sioux : “If we had wanted to travel more quickly by canoe, we could have made the trip twice.”

Justifying his earlier silence about an exploit that would have placed him among the world’s great explorers, Hennepin did not hesitate to take swipes at La Salle: “This is where I would like all the world to know the mystery of this discovery that I have hidden until now so as not to inflict sorrow on Sieur de La Salle, who wanted all the glory and secret knowledge of this discovery for himself alone. This is why he sacrificed several persons to prevent them from publishing what they had seen and from foiling his secret plans.”

Louis Hennepin published his third work in 1698. Nouveau Voyage d’un Pais plus grand que l’Europe […] reaffirmed his contribution to the discovery of North America. The missionary/author was then an undesirable subject in his own community. Due to circumstances and his thirst for fame, he had been a subject of both France and England. He was authorized to return to France in 1698, but on May 27, 1699, Louis XIV ordered that he be arrested if he ever attempted to return to New France. Louis Hennepin died after 1705 and it is not known whether he was still a Récollet priest.