The Explorers

Charles Albanel 1672

The Jesuit priest Charles Albanel was born in Auvergne, France, in either 1613 or 1616. It is not certain whether his parents were French or English. Indeed little is known about his life prior to his arrival in New France. He entered the Jesuit noviciate of Toulouse on the sixteenth of September, 1633, and subsequently started his career by teaching in various villages in France. In the spring of 1649 he embarked for Canada. Energetic and stubborn but obscure and undistinguished, looked down on by his superiors, Albanel nevertheless accepted the challenge of reaching Hudson Bay overland.

Route

Jean de Quen’s Companion

Charles Albanel arrived at Quebec aboard one of three ships that moored there on the twenty-third of August, 1649. Late the following month he carried on to Ville Marie (Montreal.) There he joined a fellow Jesuit, Jean de Quen, who had explored the Lac Saint Jean (Lake St. John) area two years before. While the latter officiated at funerals of the Montréalistes (Montrealers), Albanel officiated at their christenings. The two of them spent the winter of 1650 at the Tadoussac mission, of which de Quen was then in charge.

The territory of the Tadoussac mission extended on both shores of the St. Lawrence, so it was not uncommon to see the missionaries crossing “the highway that walks” (as the Amerindians called it) and venturing out into the terrain to meet the aboriginals who inhabited it. In the course of the next ten winters Albanel endured many hardships, but he later played them down.

The Years of Wandering

A veil of silence shrouds Charles Albanel’s next few years until he surfaces again near Trois-Rivières (Three Rivers). In 1660 he was in the company of Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard Chouart des Groseilliers when they returned from a trading expedition to Lake Superior with three hundred Amerindians and sixty canoes piled high with furs. In mid-August Albanel took leave temporarily to accompany the aboriginals who were going back to the Great Lakes.

1666 found Albanel one of four chaplains to the soldiers of the Carignan regiment commanded by Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy. That January he went with a detachment of troops who travelled on snowshoes from Quebec on a raid to scare off the Iroquois along the River Richelieu. He took part in September in a similar march by troops to the shores of Lake Champlain.

The Quest for a Route from the Northern to the Southern Sea

Just when and how did Charles Albanel come to the attention of the rulers of the colony? It is known that on the tenth of November, 1670, Jean Talon expressed his anxiety at the presence of “two English vessels overturned quite close to Hudson Bay” and the role that might have been played in their being there by “a certain Desgroseliers previously resident in Canada”. On the eleventh of November of the following year the Intendant wrote: “Three months ago I despatched Father Albanel, a Jesuit, and Monsieur de St. Simon, a young gentleman of Canada… they are to push forward as far as Hudson Bay, present written reports on all they discover, open up the fur trade with the savages, and above all reconnoitre to see whether there is cause to erect a few buildings for the winter there to make a storage from which ships might eventually be victualled if they should pass that way to discover the route between the two seas of the North and the South.”

Hudson Bay at Last!

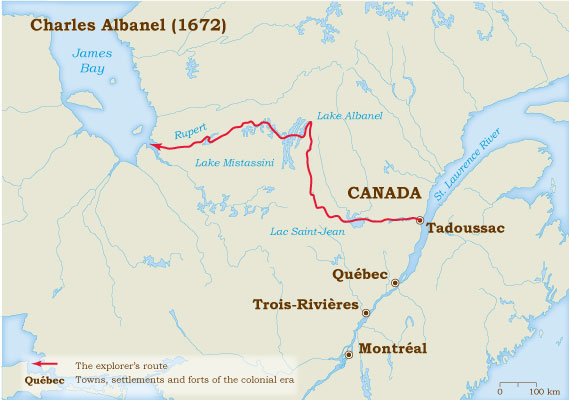

Charles Albanel, Paul Denis de Saint-Simon and Sébastien Provencher came together at Tadoussac on the eighth of August, 1671. They were at Lac Saint Jean (Lake St. John) when they received confirmation of the English presence in the Northern Sea (Hudson Bay). Despite the risk of having to delay their departure, they sent to Quebec for passports (in those days, official letters signed by the Governor, the Intendant and the Bishop). On the first of June, 1672, after a very hard winter, the three men set out again accompanied by sixteen Amerindian canoeists.

Five days later they arrived at Paslistaskau, on the watershed “which divides the lands of the North from those of the South”. On the eighteenth they entered Lake Mistassini. With the sole exception of Guillaume Couture, who had come there in 1661, no other Frenchman had ventured beyond. On the twenty-fifth, Rupert River and Lake Nemiskau opened up in front of their three canoes. They followed the Nemiskau river until it took them to the “bay of Hutson”.

Three days later they saw a ship flying an English flag and two deserted buildings left by the English. Albanel came to an understanding with the local Amerindians, emphasizing the contribution he had made to the peace that had by then lasted five years with the Iroquois: “I have snatched from him [the Iroquois] his Pakagan, his battle-axe, & have even rescued from the flames thy two daughters and many of thy kin. Very well, then, live in peace & in safety; I restore to thee they country, whence the Iroquois had driven thee. Fish, hunt, and trade everywhere, and fear nothing henceforth.”

The explorers set out on the return journey to Quebec on the sixth of July. After three days of travel they planted the standard of the King of France at Lake Nemiskau, “on the point of the Island intersecting this Lake.” On the first of August, 1672, Albanel left Chicoutimi for Quebec.

Prisoner of the English

Although Charles Albanel had succeeded in reaching Hudson Bay, he had not brought back with him any assurance that the aboriginals of the region would desist from trading with the English. Although Albanel was by then fifty-seven or perhaps even sixty years old, Frontenac (the Governor of New France) still thought he was the best man to handle the situation. So Albanel started out again for Hudson Bay in the late summer of 1673. He was not to return to the French colony until the twenty-second of July, 1676. Three days after his return he was appointed superior of the St. Francis Xavier mission (at De Pere, Wisconsin.)

The Jesuit Relations (annual missionary reports) for 1679 briefly describe the wanderings that Albanel endured on his second journey to Hudson Bay: “He suffered every hardship imaginable, only to be captured by the English who were in Hudson Bay, transported to England, and then to France…” The English took a great interest in him and spread doubts about his loyalty to the officials of the French colony. It seems that in fact he had reached Hudson Bay completely exhausted and virtually incapable of taking the same route back, so he asked the English for refuge. It was only after obtaining a letter from his superiors to clear him of the suspicion of treachery that he returned to the colony. He eventually died at Sault Ste. Marie on the eleventh of January, 1696. He was eighty or eighty-three years old.