The Explorers

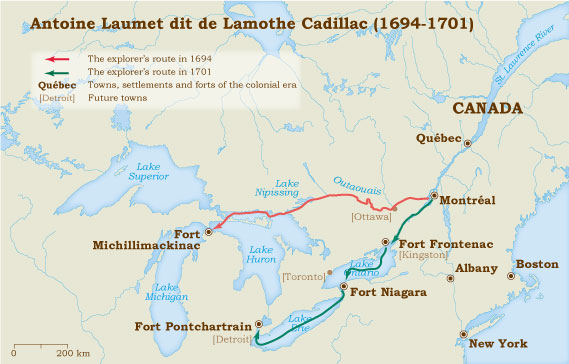

Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

Born on March 5, 1658 in Caumont, a village near Saint-Nicolas-de-la-Grave in Gascony, Antoine Laumet de Lamothe Cadillac was the son of simple middle-class parents. Upon his marriage in Quebec City on June 25, 1687, he glorified his origins, claiming his title was “Antoine de la Mothe, squire, Sieur de Cadillac, aged about 26 years, son of Jean de la Mothe, Seigneur of Cadillac, Launay and Montet, consultant to the parliament of Toulouse and of Jeanne de Malenfant.” His parents, however, were not nobility. A simple magistrate, his father was called Jean Laumet and was Seigneur of nothing at all.

This was far from being the last of the lies told by Antoine Laumet de Lamothe Cadillac, founder of Detroit, whose sojourn in New France began in Acadia around 1683. Without giving any proof, and contradicting himself on many occasions, he claimed to be an experienced soldier. No one knows where he studied, but the briefs he produced for Minister Pontchartrain indicated that he did have a certain level of education and culture.

Route

An Evil Mind

Cadillac appeared in Port Royal around 1683, in the guise of an adventurer who mingled with the men of privateer François Guyon dit Després, whose career consisted in protecting the Acadian coast by inspecting and appropriating the cargo of enemy ships. In the spring of 1687, he was in Beauport, birthplace of his employer. There, on June 25, he married a niece of the privateer, Marie-Thérèse Guyon, who would follow him in his adventures and bear him nine children.

The couple travelled to Acadia, and on July 23, 1689, he was granted a fief at Port Royal and another along the Douaque River (Union River, Maine) including Monts Déserts Island (Bar Harbour, Maine). From this time on, his nasty character attracted attention. People spoke of his “evil mind” and the rumour spread that he had been “chased out of France.” Some months later, he was in France where he began his career at court. Because of the destruction by William Phips of his holdings in Port Royal, he caught the attention of the new minister of the colonies, Louis Phélypeaux de Pontchartrain, who recommended him to governor Louis de Buade de Frontenac.

A Dream of Conquest

Frontenac took an interest in this man whose knowledge of the Atlantic Coast had been praised and who wanted to take New York, “the original source and touchstone of all the Iroquois wars.” He delegated him to France, where the project of conquest received royal assent.

With this project in mind, Cadillac and cartographer Jean-Baptiste Franquelin set out in 1692 to reconnoiter the American coastline, which they studied closely. Cadillac’s first ambitious project did not come to anything, but it enabled him to climb up the ranks. Frontenac was looking out for him, and in October 1693, Cadillac was made commander of a company. The following year, Minister Pontchartrain gave him a ship’s command, and on September 16, 1694, the Gascon eclipsed Daniel Greysolon Dulhut by becoming commander of Michillimakinac.

Master of the West

His mission in Michillimakinac consisted in consolidating the policy set up by Dulhut to ensure the stability of connections between New France and the tribes of the Great Lakes of the West. However, he had scarcely arrived at the beginning of the winter of 1694 when relations with the natives began to deteriorate. Upon his return to Quebec City three years later, the colony no longer had the privileged ties with the allies that Dulhut had brought together in 1679. From then on, the natives sold to the highest bidders: the English, with the Five Nations tribes as their intermediaries.

Indifferent to the precautions taken by the authorities of the colony over a number of years, Cadillac encouraged the distribution of alcohol and, like others before him, he did not hesitate to take part in the fur trade for his own profit. “Never before,” wrote a witness at the time, “had a man amassed so much wealth in such a short time, nor caused so much disruption through the wrongs he inflicted upon those who were involved in his dealings.”

A Project for the Detroit River

In 1698, criticized on all sides but inclined to consider himself the victim of wicked plots, Cadillac travelled to France where he presented a brief for the establishment of a permanent colony on the Detroit River. On May 27, 1699, the King decreed that it be carried out. Cadillac was commanded to achieve a six-fold mandate: prevent the beaver trade from falling into Iroquois hands ; deliver the highest quality pelts, since France was saturated with skins of mediocre quality ; ensure work for the coureurs des bois ; guarantee benefits for the merchants ; reunite the allied nations at the Detroit post and, last of all, thanks to colonists and missionaries, assimilate them into the French nation.

In Quebec City, where the implications of such a project where better understood than in Versailles, there was hesitation in putting it into action and doubts as to Cadillac’s ability to carry it out successfully. Cadillac responded in these terms to Minister Ponchartrain: “Either the plan is good or bad. If it is good, then it should be carried out. Choose a man of thought and action to execute it, and you can be assured that it will succeed, despite the secret difficulties that people want to make of it.”

The Foundation of Detroit

At the end of 1700, Versailles returned to the attack. This time, there would be no beating about the bush! The founder of Detroit left Montreal on June 5, 1701 with one hundred people, half colonists, half soldiers, and two missionaries. On July 24, the group set up on the site where the construction of Fort Pontchartrain (Detroit, Michigan) would soon begin. Three years later, after a battle against the company of the colony that had obtained the title to the fort, Cadillac became its leader.

He made an unsuccessful request for a marquisate for Detroit. Disappointed, but as ambitious as ever, he then sought to obtain an independent government for the Western posts, but governor Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil deployed all his efforts to fight the project. It was not until 1706 and 1707 that Versailles acknowledged the evidence: a colony had indeed developed in Detroit, but its presence had not consolidated ties between the tribes of the West and the French. Almost all the furs took the New York route and there was no doubt but that Cadillac had traded with the English, distributed alcohol and bribed certain Canadians who might otherwise have become his adversaries.

To the Bastille!

According to historian Yves F. Zoltvany, if the minister of the colonies had been harsh with Cadillac, he would have admitted his error. In 1710, Pontchartrain imposed disgrace by appointing Cadillac to the position of governor of Louisiana, where he did not go until June 1713. The fall was not yet over when Cadillac was already accused of having sown discontent and incited the rare inhabitants of Louisiana to leave! He is acknowledged to have attempted to establish commercial ties with Mexico, discovered a copper mine in Illinois and, above all, founded Detroit.

Recalled to France, he arrived late in the summer of 1717. On September 27, he was incarcerated in the Bastille prison along with his eldest son, awaiting judgment for having spoken “against the government of the state and the colonies.” Freed at the beginning of the following year, Cadillac returned to the good graces of the court. He was decorated with the Croix de Saint-Louis and given the governorship of Castelsarrasin, a city near his native village. He died there on October 15, 1730.