-

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

- The Explorers

- Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

- Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Economic Activities

- Population

- Daily Life

- Heritage

- Useful links

- Credits

Daily Life

Health and Medicine

All kinds of ailments were part of the daily lives of people in New France, to a greater extent than what we experience today. At that time, the causes of infectious diseases and the means of controlling their devastating effects were not well known. Medical thought and practices had little in common with those of today. Eighteenth-century knowledge about diseases and cures was still based on writings by authors from antiquity, and mortality rates were very high.

Settlers nevertheless enjoyed a good medical infrastructure. Every city had its “hôtel-Dieu,” or hospital. Surgeons, doctors, apothecaries and healers worked together with religious congregations to help care for the settlers. The Crown together with Catholic Church, played a major role in providing health care.

Illness in New France (show)

Cartier, scurvy and annedda

European exploration of the New World in the 18th century posed new medical challenges. The consequences of malnutrition on lengthy sea voyages were not understood. Travellers were limited to a diet of salted foods, including fish and meat as well as sea biscuits, a kind of dry bread that could be preserved. But the rarity—even complete absence — of fresh produce (meat, fruits and vegetables) resulted in a deficiency of vitamin C that caused scurvy.

When Jacques Cartier spent the winter of 1535–1536 at Stadaconé (modern-day the current location of Quebec) his crew was struck down by a “grosse maladie, or serious illness. By February, only 10 out of 110 men were in good enough health to help the others. More than 25 died. In his published account , the explorer describes how his men lost their strength, how their legs swelled and darkened at the extremities, and how their teeth and gums rotted. The scene, he says, “was a pity to see.” Like his contemporaries, Cartier did not understand the nature of this mysterious disease that can now be identified with certainty. When he noticed that the St. Lawrence Iroquois who lived in Stadaconé were also affected by the disease, he wrongly assumed that it was contagious and came from the Amerindians. The fact is that the Amerindians knew of a cure for scurvy. They told Cartier that a decoction of annedda leaves (white cedar) could cure the disease. Indeed, thanks to this remedy, Cartier’s crew members recovered quickly.

Epidemic diseases

The transmission of disease transformed the continent to a greater extent than the transmission of medical knowledge. The people and animals that came over from Europe to America at the end of the 15th century brought with them infectious disease strains to which the Native populations had never been exposed: cholera, influenza, measles, scarlet fever, smallpox, tuberculosis, typhoid fever and yellow fever. The impact of these diseases on the continent’s First Peoples proved to be catastrophic. Scholars estimate that as much as 90% of the Aboriginal population died.

There are many reasons for this. Wherever a given disease is common, most people are exposed to it at an early age and when they reach adulthood, they have developed a certain resistance to re-infection. This is why some diseases that were relatively benign in Europe, Africa and Asia, such as measles or influenza, proved to be devastating among Amerindians. Also, Aboriginal North American beliefs and practices were often ill-adapted to the new context. Traditional treatments that may have been efficient against pre-Columbian diseases rarely worked against foreign ones. Quarantine, for instance, was not a common practice. Thus, several smallpox and measles epidemics devastated much of eastern North America between 1620 and 1630.

Although settlers were less severely affected than their Native counterparts, they nevertheless suffered the effects of widespread contagious diseases. These had been relatively absent before 1680, but they then appeared regularly among the French population. In Canada, the first major epidemic was referred to as the “fièvre pourpre” (purple fever), and was probably a strain of typhus. This deadly disease struck in 1687 and recurred regularly afterwards. Doctor Jean-François Gaultier died of it in 1756, while treating patients new to the continent. However, the epidemic that recurred most often and with the most vigour in Canada during the 18th century was smallpox, or variola. The first occurrence in 1702 and 1703 killed 1,000 to 1,200 people, amounting to 8 per cent of the Canadian population. In 1733, 1755 and 1757, it again reached epidemic proportions. In the 1730s, Louisiana was also affected.

Varied climates

The climate, which varied considerably between Newfoundland and the mouth of the Mississippi River, had an impact on the health of colonial populations. Acadia and the St. Lawrence River valley had a cold, temperate climate. The long frigid winters limited the outbreak and propagation of many diseases. Witness accounts of that period insist on a healthy climate that was conducive to good health among the population. Pierre Boucher de Boucherville, officer and seigneur, wrote that “the air [of Canada] is extremely healthy at all times, but mostly in winter; one rarely sees diseases in these countries.” For his part, Pierre-François-Xavier Charlevoix, a Jesuit historian, wrote: “We do not, in the whole world, know of a healthier climate. There are no particular diseases.”

The situation was quite different in Lower Louisiana. This region had a subtropical climate that fostered illness. As shallow pools of calm or stagnant waters, the marshes and bayous were particularly favourable to the propagation of micro-organisms that provoked intestinal inflammation and caused dysentery. They also allowed for the reproduction of mosquitoes that transmitted malaria.

Poor hygiene

In the 17th and 18th centuries, lack of hygiene was the main cause of the outbreak and transmission of disease. In fact, bodily hygiene was nearly non-existent at the time. The morals of that era encouraged modesty and condemned nudity, thus discouraging thorough washing. Also, medical theories claimed that the air was filled with “miasmas,” that is to say microbes that penetrated the body through the skin and provoked illness. Water, especially hot water, was considered to be harmful because it opened the pores of the skin, thus making the body more vulnerable.

Water, therefore, was reserved for rare and brief washings of the hands and face, as well as for rinsing the mouth. To reduce the dangers of contagion, one might add a bit of vinegar or perfume to the water. Believing that baths could cause illnesses, people preferred “dry” baths. Wealthier people used cosmetics: perfumes and toilet water served as disinfectants and covered bad odours, while powder was used to dry greasy hair. To give themselves an appearance of cleanliness, people resorted to various artifices such as wigs. Among ordinary people, bodily hygiene was even more minimal. The habitants and artisans were content to change the long shirt they wore as underwear a few times each month and to perform a quick wash of their hands, face and neck with cold water.

Public health measures were as deficient as personal hygiene habits. New France’s low population density helped limit the destructive effects of diseases. Nevertheless, whether in the colonies or metropole, cities were sources of contagion. In the major centres—Québec, Montréal, Trois-Rivières, Louisbourg and New Orleans—streets were not paved. Domestic animals wandered freely and animals raised for meat were slaughtered in front of shops. There were no sewers, and citizens threw all kinds of garbage in public places. In the 18th century, the “Conseil supérieur” or Superior Council and administrators created laws to impose basic health measures in urban environments. In 1706, the Superior Council ruled that the houses of Quebec had to have latrines and private toilets to avoid infection and foul smells. Rather than throw garbage out the window, people now had to bring it to the river. Waterways running through the cities quickly became dirty and unfit for drinking. It is therefore not surprising that diseases ran rampant.

Everyday ailments

In the early 1740s, the docteur du roy or royal doctor, Jean-François Gaultier, left a record of the most common illnesses in the St. Lawrence colony. He describes as “putrid,” “malignant” and “poisonous” the various fevers brought over by ship. These were often the most deadly, but he also lists other types of fevers that did not cause serious problems. Respiratory diseases such as sore throats, whooping cough, angina pectoris, inflammation of the lungs, pneumonia, pleurisy and common colds were prominent in winter but usually not fatal. Canadians also suffered from scrofula (a tubericulous infection of the skin), jaundice, mumps, toothaches, diarrhea (which sometimes degenerated into dysentery), rheumatism, hernias, gout and worms. Venereal diseases were most prevelant in New Orleans, where they reached epidemic proportions.

The analysis of death registers is revealing of infant mortality in New France. In Canada, for the period between 1608 and 1760, historical demographers report an infant mortality rate of 225 per 1,000, fewer than in France. Archaeology reveal two critical stages: the perinatal and weaning stages, i.e., from one to two years of age, probably due to inadequate feeding. Indeed, bone analyses indicate a serious deficiency of vitamin D that caused rickets, as well as a severe lack of iron, which causes anemia.

Life expectancy increased after childhood but did not generally exceed 40 years of age. Only a fraction of the population reached 60 or 70 years old, and a few rare persons lived to 80 and even 100. Since a higher population density increased the risks of contagion, mortality rates were higher in the 18th than in the 17th century and were also higher in cities than in villages. Life expectancy did not increase significantly until the end of the 19th century, thanks in part to improved nutrition and public and personal hygiene.

Popular and learned theories

For the Catholic Church, illness was an expression of divine power, that is a warning, not to say a punishment. God “sends afflictions to exercise His sovereign power and to exercise His justice in punishing our sins.” During epidemics, the Church did not hesitate to remind people of these beliefs. Since illness came from God, it was the Christian’s duty to support it with patience, even joy. To heal, one had to nurse one’s soul through prayers, processions, penitence and pilgrimages.

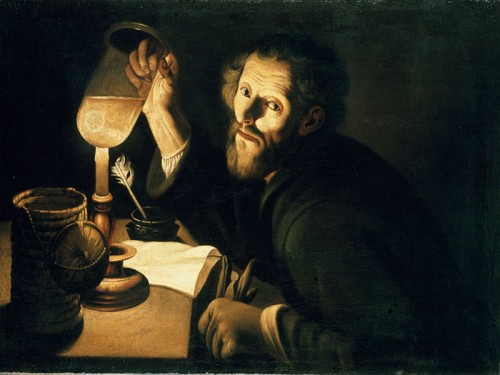

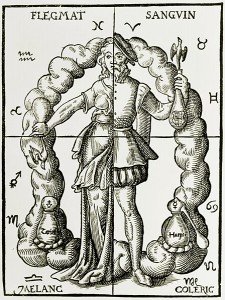

More learned medical conceptions were based on texts written in antiquity. Medical thought was inspired by the writings of the Greek doctors Hippocrates (4th century BCE) and Galen (2nd century CE). In addition to the miasma theory referred to above, it was the theory of humours that prevailed. According to this belief, health depended on an equilibrium among the four main “humours,” which were considered to be real or supposed fluids in the body: blood, phlegm , yellow bile and black bile. It was also believed that there were links between the various humours, the elements of nature, the seasons, individual temperament and the outbreak of illnesses. Depending on changes in time and the seasons, one or another of these elements prevailed. It was the predominance of a particular humour that defined temperament.

When the balance among humours was upset, due to outside forces, illness set in. Thus in winter, when phlegm was the predominant humour, there was an increase in the frequency of colds and bronchitis. It was believed that the warming of a humid climate in the spring brought on hemorrhagic diseases. The hot and dry summer climate heated up the bile and worsened bilious and feverish affections. Finally, the dry and cold autumn weather increased black bile and melancholy. To be in good health, one had to rebalance one’s humours.

Institutions and nursing staff (show)

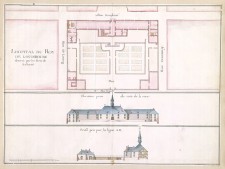

“Hôtels-Dieu” and hospitals

There were three hospital institutions to take care of the sick and wounded in the St. Lawrence colony. In 1639, three Augustinian nuns from the Hôtel-Dieu in Dieppe founded the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec. Five years later, the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal opened, thanks to the efforts of Jeanne Mance. The Sœurs hospitalières de Saint-Joseph de la Flèche took over a few years later. The Hôtel-Dieu de Trois-Rivières, founded in 1694, was managed by the Ursulines. These institutions had a varied clientele, including poor settlers and sick or handicapped people. They also welcomed many soldiers and sailors. Care of the Native population was also part of these institutions’ mission, but Aboriginal patients became fewer and fewer as the colony evolved.

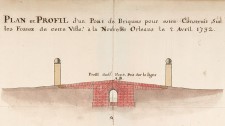

At Louisbourg, the Crown founded a hospital and entrusted it to the care of the Frères de la Charité de Saint-Jean-de-Dieu in 1716. Contrary to Canadian health institutions, which cared mostly for the inhabitants, this hospital’s major clientele consisted of soldiers and sailors. In New Orleans, the Crown created a small Hôpital du roi or King’s Hospital in 1722. It was destroyed by a hurricane shortly afterwards. In 1734 it was replaced by the Hôpital de la Charité, which was managed by the Ursulines. Small royal hospitals also existed in Port Royal, Acadia, as well as Placentia, Newfoundland.

The religious congregations played a leading role in New France, both in organizing and providing health care. In Québec and Montréal, they assumed the responsibility of financing and managing hospital institutions. In Louisbourg and New Orleans, they took on the full management of institutions founded by the Crown. Whatever the establishment, their care was aimed at saving the soul as well as healing the body.

Hôtel-Dieu and general hospital

Two general hospitals were founded in 1639: the Hospitalières nuns administered the one in Québec and the Charon Brothers managed the one in Montréal. They were followed by the Sisters of Charity. While the “hôtels-Dieu” were devoted to the care of the sick and wounded, the general hospitals of the French regime tried to resolve problems related to begging and marginal living. Their main clientele consisted of abandoned elderly people, vagabonds, the poor, the handicapped and the “insane.” They also served to confine prostitutes and other women “of ill repute.” The example of Jean-Bapiste Turpin is eloquent. This trader from Detroit had his wife locked up because she had left him three times to move in with an Aboriginal man. The first two times, Turpin took her back by force. After a third attempt, he had her locked up as a mad woman in the Montréal general hospital. However, she managed to escape to New England.

Practitioners

The nuns were not the only ones to provide health care in New France. Many lay people also played a leading role. Between 1610 and 1788, there were, in Canada, 544 practitioners: 512 surgeons, 20 apothecaries (eight of them after the British Conquest) and 12 doctors (five of whom were Anglophones after the British Conquest). Figures for Louisiana are less specific, but it is known that there were at least four royal doctors, one apothecary and a few surgeons in the 18th century.

The professional practice of these medical specialists was modelled on the French health system. Nearly all of them were born in France and had studied there, since the colonies had neither medical training facilities nor any trade corporations.

Doctors

Doctors were at the top of the professional hierarchy. Period dictionaries, such as Antoine Furetière’s Dictionnaire universel contenant généralement tous les mots françois (La Haye and Rotterdam, 1694), defined a doctor as: “One who has studied the nature and illnesses of the human body, who has made it his profession to heal human beings, who practices the art of giving or conserving health”. The doctor was therefore considered to be a man of science. He concentrated his practice on three specific aspects that required a good knowledge of everything related to medicine and pharmacy: the diagnosis (identifying the ailment), the prognosis (predicting the evolution of an illness and possibilities of a cure) and the prescription (choice of a treatment).

The doctor differed from the surgeon and apothecary by his university degrees, which were a recognition of his essentially formal and theoretical training. His position in the professional hierarchy was determined by his titles and diplomas. Thus the docteurs du roy or royal doctors were at the top of the colonial medical hierarchy and as such, they had to have a doctoral degree. Yet a bachelor’s degree was usually sufficient to practice medicine. In Canada, the most important doctors were Michel Sarrazin (1699–1734) and Jean-François Gaultier (1742–1756). In Louisiana, they were Louis Prat (up to 1735) and his brother Jean (1735–1746), Jacques Benigne de Fontenette (1746 to about 1760) and François Lebeau (from 1760).

The royal doctors had to watch over the health of the colony. He went to the Hôtel-Dieu in Québec or in New Orleans every day to see the patients cared for by the nuns and to discuss with the apothecary the medicine that needed to be prepared and administered. He rarely went to other cities that had an Hôtel-Dieu, and where the nuns relied on the help of a few surgeons. The doctor also had to take care of the military troops. In the case of epidemics, he had the right to intervene and to determine what measures needed to be taken to limit the spread of the disease. In addition to all of these obligations, he cared for a private clientele composed of religious and lay people.

Surgeons

As in France, surgeons made up the largest proportion of health care specialists in the colony. During the French regime in Canada, they represented at least 90 per cent of health professionals.

Unlike doctors who trained in universities, surgeons had to undergo an apprenticeship with a master, followed by an internship in a hospital, or with the armed forces . It was only after about six years of training that candidates could pass a master’s examination. In principle, doctors were responsible for internal medicine while the treatment of wounds and external ailments were left to the surgeon. Practice, however, was rather more fluid. The first surgeons did not hesitate to get involved in general medicine and pharmacy. They sometimes prepared their own medicines, but most often they bought them from apothecaries and sold them to their patients in the form of plasters, ointments and balms. While doctors normally practised only in institutions and in cities, surgeons regularly went out into the country and to remote areas.

There was also a hierarchy among colonial surgeons. At the top of the pyramid was the lieutenant of the first surgeon of the king. In the middle were the ordinary surgeons of the king and the army’s major surgeons. Simple surgeons were at the bottom of the pyramid. The role of lieutenant of the first surgeon of the king appeared in Canada in 1658, with the arrival of Jean Madry, and it disappeared in 1742, with the death of Jourdain Lajus. He was the one who could authorize the practise surgery in the colony and he supervised the work of other surgeons.

Apothecaries

The apothecary was the forerunner of the pharmacist. The three main functions of an apothecary were to prepare, preserve and distribute medication. Louis Hébert, Canada’s first settler to land in Québec in 1617, was an apothecary and grocer in Paris. However, he came to the colony not to practise his profession but to cultivate the land. The apothecary’s profession evolved in large part thanks to such institutions as the “hôtels-Dieu” and hospitals, and to Québec’s Jesuit College, all of which had their own apothecary. In the institutional context, this position was not not unfrequently occupied by a nun. The colony also numbered a few independent apothecaries: Claude Boiteux de Saint-Olive in Montréal, Jean-Baptiste Chrétien in Québec, Alexandre Veille and the Damaron and Moulin families in New Orleans. Apothecaries’ shops, often located in their homes, were usually divided into two sections: a public space where medicines were displayed on shelves, and a private space that served as a laboratory and stockroom. With a medical prescription issued by a doctor or surgeon, wealthy patients or their servants usually went to the apothecary—clerical or non-clerical—to obtain medication. In the country, patients could sometimes obtain medication from the parish priest.

Midwives

As in France, birthing in New France was the exclusive domain of women. In addition to family members and friends, midwives attended women giving birth. Before the early 19th century, doctors and surgeons rarely intervened in childbirth.

At the beginning of the colony, midwives were self-trained. The first professional midwife, Marguerite Langloise, worked in Québec as early as 1654. Midwifery as a profession was institutionalized early in the 18th century when the Bishop of Quebec, Monseigneur Jean-Baptiste de Saint-Vallier, recommended that midwives be elected by the women of the parish gathered in a meeting. Following approval of the election by the parish priest, the midwife took an oath.

Michel Sarrazin worried about the shortage of midwives and recommended that authorized midwives receive a salary. Midwives in the country, however, long resisted payment for their work. As was the case with the doctor and surgeon of the king, a midwife’s position supported by the Crown was created with the arrival of Madeleine Bouchette in 1722. This position was reserved for French women who had undergone training at the Hôtel-Dieu de Paris. Similar measures were taken in New Orleans where, around the same time, the Company of the Indies sent and maintained a midwife.

Healers

Here and there in the country, one could find some people who bled (to balance the humours), dressed wounds and attended to patients suffering from all kinds of ailments. They had no official authorization but were supported by the local population. Such was the case of Yves Phlem, from Brittany, who settled in Notre-Dame-de-la-Pérade around 1720.

Settlers suffering from sprains, dislocations or fractured limbs sometimes resorted to self-taught healers. In France, these were referred to as “rebouteurs” or “rebouteux,” “renoueurs,” “rhabilleurs,” “mèges” or “bailleuls,” but in Canada they were better known as “ramancheurs” (bonesetters). Their know-how was based on both traditional and scientific knowledge. They massaged muscles and ligaments and repositioned bones.

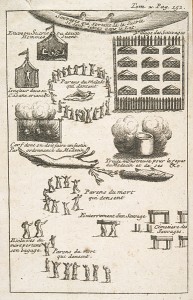

Generally speaking, the French who settled in North America from the beginning of the 17th century had little interest in the medical practices of the “Savages.” They were suspicious of the evil-looking rituals that accompanied the preparation and administration of remedies among the First Peoples and preferred to stick to their own expertise and knowledge. There were a few exceptions, among them the Jesuit priest Joseph-François Lafitau, who stayed at the Sault-Saint-Louis mission (Kahnawake) near Montréal for many years. Referring to the medical practices of the Iroquois, he wrote: “The healing of wounds is the masterpiece of their operations … They are equally successful in treating ruptures and hernias, dislocations and fractures.” In Louisiana, according to writers Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz and Jean-François-Benjamin Dumont de Montigny, many settlers preferred the care of Native healers to that of surgeons, who tended to resort somewhat too quickly to amputation as a way of dealing with infections.

Caring (show)

Blood-letting, purges and enemas

In his masterpiece The Imaginary Invalid, the French playwright Molière wrote a sharply humorous scene in which a medical student is undergoing an examination in order to become a doctor. The university masters take turns questioning him in Latin. When asked how he would treat a case of dropsy, the candidate responds: “Clysterium donare, postea saignare, ensuita purgare. “Give an enema, then bleed and finally purge.” When presented with a patient suffering from headaches, fevers and abdominal pain, the student gives the same response. In an attempt to trap him with a trick question, a third master asks what he would do if this cure did not work. The candidate replies, triumphant: “Give an enema, then bleed and finally purge. Then give another enema, bleed again and re-purge.” Delighted, the jury applauds, congratulates him and awards him the title of medical doctor.

This parody bears witness to 17th-century medical practice. According to the beliefs of the time, there were three factors that contributed to human health: food, drink and fresh air. Blood-letting, purges and enemas were the three most common remedies. According to the humours theory, these treatments helped rebalance humours in the body through purges of all kinds. It was believed there was nothing better to combat disease than to evacuate all negative humours through abundant blood-letting, which the doctor, or more often the surgeon, would undertake with a lancet. Blood-letting was used to treat just about everything, and everyone, from babies to the elderly, was apt to undergo such a treatment.

Purges consisted of giving patients vomiting or laxative medication, always with the intention of evacuating harmful humours. The “clyster” designated the enema itself as well as the instrument that was used to administer it. The operation consisted of introducing into the anus a syringe filled with water and vinegar, and injecting this substance in the intestines. Enemas, which were prepared and administered exclusively by apothecaries, tended to disappear in the 18th century.

Operations

Beyond blood-letting, the field of surgical interventions was broad. At the time, the surgical discipline could be divided into two categories: minor and major surgeries. According to the dictionaries of the time, minor surgeries included the incision of abscesses, the use of cauteries and cupping glasses, the treatment of fractures, wound dressing, teeth extraction and blood-letting, as well as the treatment of venereal diseases. Major surgeries included more complex operations, such as amputations, the removal of various tumours, the extraction of urinary stones, the reduction of hernias, trepanations and cesarean sections. Major surgery was left exclusively to the most experienced practitioners and underwent a remarkable evolution as a result of the wars, which provided opportunities to experiment with new methods.

In spite of growing knowledge regarding anatomy and surgical techniques, operations remained very dangerous. In the absence of hemostatic forceps, it was difficult to prevent hemorrhages. Alcohol and certain opium-based products relieved pain but did not eliminate it. A patient’s pains, which could be atrocious, demanded quick action. Without anesthesia or aseptic and antiseptic measures, surgeons limited themselves to treating external maladies and rarely practised interventions on internal organs. Dexterity and rapidity were essential for a good surgeon.

Breast cancer operation by Michel Sarrazin: a great success!

In 1700, at the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, the royal doctor Michel Sarrazin practised what is believed to be the first mastectomy in North America. He removed a cancerous tumour from the breast of Sister Marie Barbier de l’Assomption, who had been Mother Superior of the Congrégation Notre-Dame in Montréal. Sarrazin, who had diagnosed the “cancer,” wrote:

“No matter what option I choose, I see my Sister de l’Assomption in danger of an imminent death. If we don’t operate, she will surely die within a few days, since she is getting worse by the day; and to attempt an operation will nearly inevitably lead to her death, since there is hardly any hope that she could sustain it and even less hope that she could recover from it.”. Cited in Arthur Vallée, Un biologiste canadien : Michel Sarrazin 1659-1735, Sa vie, ses travaux et son temps (Quebec: Proulx, 1927), p. 291

The operation took place on May 29 and was a resounding success. The nun returned to Montréal shortly afterwards and died in 1739, at the venerable age of 77.

Medication

The basic components of medicines came mainly from so-called “simple” medicinal plants. These were mostly flowers, leaves, resins, roots, bark, fruits, seeds and ground flours. Products from animal sources were also used (eggs, milk, butter and honey, but also horse manure and crab’s eyes), as well as minerals (sea salt, alum, antimony, sulphur, mercury, lead, amber and coral). The apothecary transformed these various elements with the help of mortars and pestles, ovens and stills.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the choice of medication rested in part on empirical considerations, that is on past experiences that led to the establishment of a link between a given disease and a particular treatment. However, health professionals preferred what they called “rational” considerations, in which the relationship between an illness and a remedy was determined through reasoning. This reasoning was based on the theory of humours, wherein basic ingredients were classified according to four elements (water, air, fire and earth) and four characteristics (humid, dry, hot and cold). For example, since the willow and the queen-of-the-meadows came from a humid environment, they were used to treat rheumatism.

Practitioners also resorted to the “signatures” theory proposed by Hippocrates and renewed by Paracelsus (1493–1541). This theory rested on similarities between the form and colour of plants and the ailment observed in the patient. For example, the leaf of the lungwort was used to make a herbal tea to treat pulmonary diseases because this plant resembled the lungs. The meadow saffron from the lily family, which had tubers, was used to treat gout.

American “simples”

From the beginning of the colony, medical authorities and practitioners took an interest in plants and other medicinal products. Royal doctors Sarrazin and Gaultier distinguished themselves as naturalists and corresponded with their colleagues from the Jardin du Roi (Garden of the King) and the Académie des sciences (Academy of Sciences) in Paris. The integration of local knowledge into medical practice, however, was rather sporadic and had very little impact on the evolution of medicine. This field remained essentially European in its conception and application. The use of North American products in the colony’s pharmacopoeia was minimal. Of the 1791 substances mentioned in post-mortem inventories compiled by Canadian practitioners between 1669 and 1800, there were barely eight local products, among them maidenhair fern, ginseng and beaver derivatives.

Indeed, the beaver was not hunted only for its fur. Its meat appears in diets prescribed by doctors. Its kidneys, like the hooves of deer and moose, were used to treat mental ailments. Other practitioners, who had no medical training other than experience and observation, used beaver products to treat other ills, much in the same way as they used bear or skunk grease. Castoreum, a secretion found near the beaver’s genitals, was used to treat hysteria and neurosis.

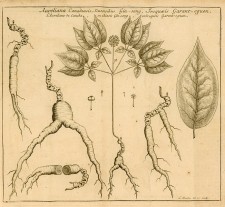

At the time, maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum) was appreciated for its use in treating respiratory problems as well as for its ability to stimulate the appetite and supposedly to temper humours. It was taken as a syrup and progressively replaced its French rival, the Montpellier or black madenhair fern. American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), identified by the Jesuit priest Joseph-François Lafitau, enjoyed a huge popularity. Used locally, ginseng was also cultivated on a wide scale for exportation to China, via La Rochelle, especially between 1747 and 1752.

Although it does not feature in post-mortem inventories, the Canada balsam (in the form of a liquid or gum resin from fir or spruce trees) was also used by the colony’s medical practitioners. Doctor Gaultier outlined a variety of uses in addition to the healing of external wounds: the treatment of kidney diseases in the case of urinary malfunction, and of abscesses of the lungs and bladder ulcers. Canadians took it as a purgative, with olive oil.

Cost of health care

At the “hôtels-Dieu” and in hospitals, the cost of heath care varied according to the patient’s social condition. It was free for the majority of the population, but wealthy people had to pay, at least in part, for the care they received. On average, a blood-letting treatment in the arm cost one livre (as the French currency of the time was called) , while the same treatment in the leg cost two livres. In 1721, most of the medication administered by Major Surgeon Joseph Benoît, a senior army surgeon, cost between one and three livres. The cost of dressing a wound varied from 15 to 20 livres, while keeping vigil at someone’s bedside at night cost six livres.

Debts for medical services, which were usually registered in post-mortem inventories, provide a good estimate of health costs. Surveys from the government of Quebec show amounts running from 1 to 182 livres per individual. As a point of comparison, a tradesman earned 360 to 500 livres per year and a day labourer from 100 to 120 livres.

Royal doctors and army surgeons were paid by the Crown. Royal doctorMichel Sarrazin received 300 livres the year he arrived, 600 livres in 1701, 800 in 1706 and 1,100 in 1718. In order for him to receive these amounts, the colonial authorities had to intervene with the king on his behalf on several occasions. Sarrazin’s successor, Jean-François Gaultier, received 1,200 livres in 1744. Doctors also received supplementary income from their private patients. In 1726, a senior army surgeon Joseph Benoît received about 1,000 livres, to which could be added 300 livres for his role as doctor, another 300 for his acting as surgeon to the “Savages” and 200 livres for his position as surgeon at the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal. In total, Benoît received some 1,800 livres in a single year, an imposing sum at the time. On the other hand, many of his colleagues would have had to scramble hard to earn a living.

Miracles

Praying was a common practice in the colony but it became more intense when one could not afford the required health care, or when a medical intervention was not successful. Devotions of all kinds increased during epidemics. In New France, Sainte-Anne-du-Petit-Cap on the hill at Beaupré was the most popular pilgrimage destination. Many sick and crippled people went there hoping for a cure, or vowed to go as soon as they could afford to.

The first miraculous cures to occur at Sainte-Anne were reported as early as in the 1660s. The case of Jean Salois is well known. On October 23, 1669 Salois was hit with an axe on the knee. In spite of treatments by two surgeons, he remained crippled. On March 1, 1670 he went to the church at Sainte-Anne de Beaupré to reaffirm a vow he had made years before. Seven days later, a miracle happened: Salois walked away without any crutches or walking stick. Many people who had been cured made the pilgrimage to thank Saint Anne.

Conclusion (show)

The state of health in New France was comparable to that in Europe at the same time. As in France, ignorance of basic hygiene greatly increased the risk of infection and contagion. , As in France, the colony was prone to periodical epidemics that increased mortality rates.

However, with the exception of settlers in the unhealthy region at the mouth of the Mississippi River, people in New France enjoyed a better state of health than their counterparts in Europe. The lower population density,, limited contagion, as did the cold, temperate climate. As well, , health institutions were well managed and sufficient in number to respond to the population’s needs, and the nursing staff was dedicated and highly devoted.

Suggested readings (show)

DUFFY, JOHN. “Pharmacy in Franco-Spanish Louisiana,” in American pharmacy in the colonial and revolution periods, symposium in New Orleans in 1976, American Institute of the History of Pharmacy, Madison (Wisconsin), 1977, p.15–24.

HOAD, LINDA M. La chirurgie et les chirurgiens de l’île Royale, Ottawa, Parks Canada, 1979.

LAFORCE, HÉLÈNE. Histoire de la sage-femme dans la région de Québec, Québec, Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture, 1985.

LEBRUN, FRANÇOIS. Se soigner autrefois. Médecins, saints et sorciers aux xviie et xviiie siècles, Paris, Temps actuels, 1983.

LESSARD, RÉNALD. Se soigner au Canada aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, Hull, Musée canadien des civilisations, 1997.

LESSARD, RÉNALD. Pratique et praticiens en contexte colonial: le corps médical canadien aux xviie et xviiie siècles, Québec, Université Laval, doctoral thesis in history, 1994.

ROUSSEAU, FRANÇOIS. La croix et le scalpel. Histoire des Augustines et de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, volume 1: 1639–1892, Québec, Septentrion, 1989.

SALVAGGIO, JOHN E. New Orleans’ Charity Hospital: a story of physicians, politics, and poverty, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

TÉSIO, STÉPHANIE. Histoire de la pharmacie en France et en Nouvelle-France au xviiie siècle, Québec, PUL, 2009.

VALLÉE, ARTHUR. Un biologiste canadien : Michel Sarrazin 1659-1735. Sa vie, ses travaux et son temps, Québec, Proulx, 1927.