-

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

- The Explorers

- Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

- Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Economic Activities

- Population

- Daily Life

- Heritage

- Useful links

- Credits

Daily Life

Entertainment

People have always needed distraction and relaxation to get their mind off things for a while. The inhabitants of New France were no exception.

How did the inhabitants of the French colonies in North America spend their free time? That is the subject of this article, which begins with a look at theatrical and musical performances, a form of entertainment that attracted many people, as was the case in France, even though religious authorities were sometimes adamant in their condemnation of it. The first play was staged in Acadia on November 14, 1606. Dance performances, song recitals and concerts, improvised or organized, were equally well received by the people of New France.

Reading was also a favourite pastime among the members of the population who could read and preferred to relax at home. However, since all books were published in France, they were not easy to come by. What characterized literary life in New France and what types of literature were found in the colony’s libraries? A painstaking analysis of estate inventories provides the answer.

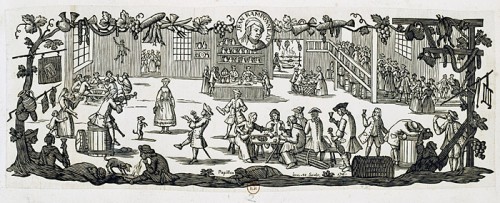

This article also looks at inns and taverns, ideal places to end an evening. Inns and taverns played an important role in social life, just as they do today. These meeting places were easily accessible, and people gathered there to play billiards or skittles, lose their money in games of chance, and even fight.

Performances (show)

Music

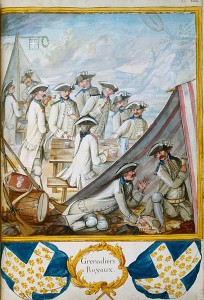

In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century society, there seems to have been a widespread taste for music. The lives of the first colonists were punctuated by the sounds of church bells, drums and military fife music. Music became an integral part of religious practice in the early seventeenth century. Sung masses appeared around 1647, and records show that, about ten years later, Notre-Dame Church had an organist. The Jesuits also taught singing in their schools. In 1666, François du Moussart, a nineteen-year-old drummer from the Carignan Regiment, was hired as a music teacher. The violin music heard at the Ursuline convent delighted Aboriginal women. The many ceremonies organized by the clergy included songs, music and hymns for every station along a procession route. The ceremony that marked the inauguration of the cathedral and bishopric of Québec in 1684 lasted half a day, culminating in a Te Deum accompanied by music, the ringing of the church bells and the sounds of the city’s artillery.

Music was not heard solely in military and religious settings; a selection of estate inventories reveals that about fifty people owned musical instruments. Three-quarters of them were prosperous merchants or individuals involved in commerce in one way or another. Their collections included bombardes and jew’s harps. The jew’s-harp — a small metal instrument that is struck with the fingers close to the lips to produce vibrations — appealed immensely to Aboriginal people. Merchant Raymond Dubosc had close to 600 of them in his inventory in 1697. Some high-ranking officials, military officers and artisans also owned musical instruments. The violin was the most popular instrument, but the notables of Québec, Trois-Rivières and Montréal also possessed guitars, harpsichords, viols, portable organs, flutes, flageolets and bugles. At his residence, the Intendant of Québec, Claude-Thomas Dupuy (1726–1728), could receive his guests with music; he had a twelve-stop cabinet organ, a portable spinet, two English bass viols, and numerous volumes of songs and sheet music.

Singing

Singing played an important role in the lives of Canadian colonists, who often sang at the dinner table. In her letters, Élizabeth Bégon describes lengthy dinners where guests sang so loudly and so well that passers-by stopped to listen. In court archives, one regularly finds reports of colonists or Aboriginal people singing in the streets, often while drunk. The archives also contain reports of soldiers sitting in taverns copying songs into songbooks. Since such information is often drawn from records of trials related to the forgery of orders to pay , the transcription of songs was no doubt a means of covering up illegal acts.

Apart from Menuets chantants and Clef de chansonniers, two volumes listed in some inventories, it is hard to tell what drinking songs or more serious melodies were sung by colonists. In 1707, Montréal butcher Henri Catin was wounded by Captain Guillaume de Lorimier in his son-in-law’s inn because he had awakened the soldier by singing: La Belle passant par dessus le pont le vent leva sa cotte fit voir son talon (As the pretty girl crossed the bridge, the wind lifted her petticoat, revealing her heel). The soldier’s anger was such that only this stanza has survived. In 1747, during a trial for the forgery of orders to pay, a witness who lived on Rue St-Paul, in whose home the two defendants were boarders, testified that he had seen one of them, soldier Guillaume Jacques Wouters, known as Duchateau, writing a song with four couplets. “The first began as follows: Je ne veux plus vivre dans le monde puisqu’en vivant je suis si malheureux [I no longer want to live in the world, so unhappy am I]; the second, as follows: arrêter donc cette estime adorable que mes soupirs vous fléchissent le cœur [stop this adorable esteem, let my sighs win your heart]; the third: mon cher amant ne soit point en colère je t’en prie ne me veux pas de mal [my love, do not be angry, do not wish me harm]; and the fourth: combien de fois ai-je exposé ma vie à la rigueur d’un injuste rival [how many times have I exposed my life to the harshness of an unjust rival]”.

In New France, songs were frequently satirical in nature and could necessitate apologies, or lead to fines and, sometimes, punishment in an iron collar in the public square. In 1709, Lambert Thuret, known as Prévost, a corporal in the d’Esgly Company, and Jean Berger, a painter, were jailed when apothecary Claude Boiteux de Saint-Olive filed a complaint accusing them of assaulting him. While in prison, Berger wrote a song “in the key of A” that ridiculed not only the victim, but also the authorities. According to the song, after he was beaten, Saint-Olive summoned the “gentlemen of the law” and paid them handsomely to punish the offenders:

Il [Saint-Olive] envoya quérir soudain

Messieurs de la justice,

Donnant l’argent à pleine main

Pour qu’on les punisse

The song concludes:

Ceux qui auront plus profité

De ce plaisant affaire,

Messieurs les juges et les greffiers

Les huissiers et notaires,

Ils iront boire chez Lafont

Chacun en se moquant de lui [Saint-Olive].

(The ones who benefited the most from this amusing affair were the judges, clerks, bailiffs and notaries. They’ll go have a drink at Lafont’s, each of them mocking Saint-Olive.)

This satire earned Berger an hour in the iron collar in a public square in Montréal. The signs placed in front and behind him read: Auteur de Chansons (songwriter).

Dance

Dance, like theatre, was a form of entertainment that was always subject to disapproval by the Church. The first references to dance in the colony appear in the context of a wedding, that of a soldier named Montpellier and the daughter of Charles Sevestre. A volume of the Jesuit Relations dating from 1646 mentions “a kind of ballet — that is, five soldiers”. The previous year, two violinists played at a wedding reception at the home of Sieur Couillard. Those violinists most likely accompanied a few dancers, since dancing was quite popular at weddings in France. In 1667, Louis-Théandre Chartier de Lotbinière organized the first ball for Québec’s bourgeoisie, to celebrate his appointment as lieutenant-general of the Provost’s Court. The members of the Confrérie de la Sainte-Famille who attended the ball were expelled from that sisterhood by the bishop, Monseigneur de Laval. His successor, Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier, never missed an opportunity to denounce dances and balls as offences against decency. The few pastoral letters he issued in 1691 forbade these and other forms of entertainment on Sundays and feast days.

Despite the censure of the religious authorities, dancing continued to be enjoyed in New France. Historian Bacqueville de la Potherie, who was in Canada in 1699 and 1700, spoke of Canadian women who were “witty, tactful, had a good singing voice and were much disposed to dancing”. A century later, while visiting Louisiana, West Indian planter Louis-Narcisse Baudry Des Lozières observed that dancing was very popular there as well. According to him, Louisiana was the land where people danced the most.

In France, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the minuet and the contredanse replaced the branles, bourrées and rigadoons of the Middle Ages. New France’s bourgeois society, as well as some members of the military, became familiar with these dances. The arrival of Intendant François Bigot in Canada, in 1748, and his love of festivities, had repercussions on dancing. The preparations for the arrival of the intendant and his entourage in Montreal led Élizabeth Bégon to lament in a letter: “There are not enough teachers for all those who wish to learn to dance.” The demand for dance teachers seems to have been fairly high in Louisiana as well, which explains the deep regret expressed at the loss of a dance teacher named Baby, who was killed by the Choctaws.

The members of the working classes did not all dance the minuet, but they enjoyed kicking up their heels in a contredanse. In 1686, soldiers and inhabitants of La Prairie Saint Lambert got together to eat, drink and dance on the days meat was allowed. The mother of two young people invited to one of the get-togethers reported: “… the inhabitants who ate a bit and drank eau de vie that people had brought for their meat day … after dancing with them …” In an account dating from 1757, when the Seven Years’ War was raging and rationing had begun, Robert Duhaut, the bailiff of the Conseil supérieur de Québec and a resident of Rue Saint-François, declared that: “the woman named Millet entered the home of the one called Vadeboncoeur with two soldiers, which he saw from his door, being the closest neighbour, and he heard a lot of noise coming from the house, and their jumping and dancing made the floor shake …”

Theatre

On November 14, 1606, Samuel de Champlain and Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt returned from an exploration of the coast. They were welcomed in Port-Royal, Acadia, with a performance of Muses de la Nouvelle-France, featuring characters from Greek mythology. Neptune, with long hair and beard, held a trident and was seated in a chariot pulled over the waves by six Tritons. The author of the show, Marc Lescarbot, most likely also composed the music. His work, which combined French verse and the Mi’kmaw language, paid tribute to the colony’s leaders and celebrated the glory of King Henry IV. To the sound of trumpets and cannons, Lescarbot’s aquatic show, staged on barges and canoes in Baie française (the Bay of Fundy), inaugurated theatre in French North America. When the next theatrical performances were presented, New France already had its first governor, Charles Huault de Montmagny. He never missed an opportunity to organize festivities, both to amuse the colonists and captivate Aboriginal people. Indeed, religious ceremonies and processions were often followed by profane festivities. Cannon and musket fire, as well as fireworks, made a strong impression. For New Year’s and other celebrations, the governor, the members of religious orders and most of the country’s inhabitants visited one another, sent each other greetings and exchanged gifts.

In 1640, Montmagny’s secretary, Martial Piraube, staged a play in Québec to mark the birth of the future King Louis XIV. In 1646, the spirit of chivalry was celebrated with a presentation of Le Cid, whose author, Pierre Corneille, had been Montmagny’s schoolmate. Students of the Collège de Québec staged plays by Corneille and Racine, which were performed before the governor. The Jesuits had their works performed by their students. In addition to the Passion play in Latin, they presented dramas in five acts that always had moralistic themes. The Ursulines also staged short moral and religious dramas called pastorals. In those educational settings, theatre was not used to train actors; it was, rather, a memory exercise, and helped students prepare for public speaking and learn how to present themselves in public. It goes without saying that female characters were forbidden in the plays presented in schools for boys.

The tragedies of Racine and Corneille were meant to edify the audience and convey a moral, since the public identified with the heroes. With comedies, it was altogether different. In France, the Jansenists (strict Catholics who favoured rigorous abstinence) wanted to ban comedy, since it stirred the passions, particularly those of the flesh. In the spring of 1693, the arrival in Canada of Jacques-Théodore Cosineau de Mareuil, a discharged naval lieutenant, amateur actor and protégé of Governor Frontenac, led the Church to take a tougher stance with regard to theatre and comedy. After staging Corneille’s Nicomède and Racine’s Mithridate at the Château Saint-Louis, Mareuil wanted to present Tartuffe, by Molière, the most prominent author of comedies in France.

Le scandale du monde est ce qui fait l’offense,

Et ce n’est pas pécher que pécher en silence.

(Tartuffe, act IV, scene v, lines 1505–1506)

(The public scandal is what brings offence, / And secret sinning is not sin at all.)

Was it the meaning of these lines that provoked the ire of New France’s second bishop, Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier, or was it the play itself, which attacked sanctimonious individuals who were too often hypocrites? The bishop of Québec was in fact echoing the repressive attitude of the archbishop of Paris, who, some 30 years earlier, had opposed and condemned the first performances of Tartuffe. Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier issued pastoral letters against comedies, and when he instructed priests to preach against impious speech, he was targeting the freethinking Mareuil, whose remarks were sometimes considered blasphemous. Mareuil protested, and the matter was brought before the Conseil souverain. He was subsequently arrested and sent back to France on the last vessel to leave in 1694. Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier managed to cancel the presentation of Tartuffe by spending about a hundred pistoles, and then he, too, went to France. Upon his return to the colony, he took up the battle against impious entertainment with renewed zeal. In a general pastoral letter dating from 1700, the bishop included a series of activities and places that were off-limits to clerics: shows; balls; assemblies; banquets; fairs; markets; inns, taverns and other places where alcoholic beverages were offered; trials; games of chance, court tennis or boules in public places; and even hunting.

The Church’s continued disapproval of theatre did not lead to the disappearance of the performing arts. The Ursulines got around the restrictions by presenting mythological and bucolic sketches. In 1700, a man named Montmorency, likely a soldier, was paid 20 livres to give a puppet show that was presented from Epiphany to the end of Lent. And in a letter written in 1749, Élizabeth Bégon reveals that comedies were once again being performed.

Reading (show)

Books in New France

There were no printing presses, bookstores or public libraries in New France. Less than half the colony’s population could read and write, a proportion comparable to that found in many regions of France at the time. Yet, books were present in the life of the inhabitants and circulated within the colony. Religious communities and schools used them for cultural and educational purposes, while professionals viewed them as tools or a form of entertainment. A sampling of 2,500 estate inventories dating from 1635 to 1760 gives us a fairly accurate idea of the presence of books in homes. Books are mentioned in about 20% of the inventories, more frequently in those of city dwellers than in those of rural inhabitants. Book owners accounted for 30% of the population of Québec, 15% of that of Montréal and Louisbourg, and 10% of that of Trois-Rivières. Despite the absence of printers and bookstores, close to 450 people owned books, for a total of about 8,000 volumes.

Books were found at all levels of society, but more so among the more educated classes and older people. Prosperous merchants owned a quarter of the libraries inventoried. Books were very important to State officials and members of the clergy, who had the largest libraries. They were less common at the lower end of the social ladder, where they appear to have been relatively rare; 60% of private libraries contained less than 10 books. That was the case in libraries belonging to unskilled workers, such as domestics and most artisans. Only three libraries contained more than 1,000 books.

Book lending contributed to the dissemination of books and reflected the population’s interest in reading. In 1734, the attorney general of Louisbourg, Antoine Sabatier, sent his colleague in Québec, Guillaume Verrier, a copy of Mercure historique. Sabatier noted that the book was worth the trip, and he invited Verrier to lend it to others who, in turn, would tell him which books they would like to receive. Books were not found only in medical circles and among high-ranking officials. According to historians, a priest named Boucher from Saint-Joseph-de-Lévy lent his parishioners books, and archives confirm the role of the Séminaire de Québec in circulating books. There are some amusing facts related to books. In 1732, notary Étienne Dubreuil went to court to reclaim three books, two of them religious, that he had loaned to joiner Jean Valin. Valin refused to return them, claiming that he had not yet finished reading the third book. The literary tastes of carpenter Jacques Ménard, or his wife, Angélique Delisle, are surprising; he read not only the memoirs of Cardinal Richelieu, but also a history of Japan!

The auction of the library of Attorney General Guillaume Verrier in February 1759, the largest in New France, reveals the population’s interest in books. Nine hundred works were sold for a total of about 9,000 livres tournois. While the Marquis de Montcalm purchased only one volume at the auction, a soldier known as Tremble-au-Vent bought six. Even in the midst of the Seven Years’ War, and despite the shortages that had existed in the colony since 1757 and the defeats of the summer of 1758, close to one hundred people invested considerable sums in books. Some titles, especially dictionaries, fetched up to 250 or 300 livres. An officer named Dumas paid 250 livres for Bayle’s eight-volume dictionary. Moréri’s dictionary, in 10 volumes, was estimated at 60 livres, but a surgeon named Arnoux paid 300 livres for it. The person who spent the most at the auction — 800 livres — was a man named Robin. A notary called Panet spent almost as much, 725 livres tournois. Inflation no doubt accounts for the high prices. However, investing in books meant that less money was available for the purchase of other goods, such as food.

Literary Genres

What titles were found in libraries? The Livre d’heures (Book of Hours) is the book most often listed in estate inventories, about a hundred times. It was no doubt popular because some editions were well illustrated, but especially because it presented the rules one had to follow to lead a good Christian life, including daily prayers and meditations in preparation for the sacraments.

Some law books were very popular; L’ordonnance de la Marine de 1681 and Coutume de Paris were the sixth and seventh most often cited titles. In a society where the military played an important role, the virtual absence of military codes is surprising. The governors were perhaps right in saying that Canadian officers knew nothing about basic military discipline. Among the works of historians and geographers, those that dealt with the history of France and North America were the most numerous. Biographies of French politicians and accounts of travels in North America confirm the popularity of French works. Treatises on the continents, both geographical and historical, allowed certain readers to discover the four corners of the globe and provide evidence of an openness to the outside world.

Le parfait négociant, by Jacques Savary, is the work most often mentioned in scientific libraries. The works of Ambroise Paré, the father of French surgery, were found in the collections of a doctor Sarrasin and in those of two surgeons, Roussel and Baudeau. It is surprising to note that in the fortified city of Québec, where housing was a key issue and shipbuilding was important, only six libraries held treatises on architecture, and only three had shipbuilding manuals. About ten inventories also featured musical works.

Literature appears to be the most varied category, with close to 200 authors. Proponents of classical and contemporary literature, poets, social and political critics, letter writers, philosophers and religious writers — all the great names of French literature from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries were found on the shelves of colonial libraries. The presence of primers and dictionaries also attests the interest of the early settlers in self-education and the art of writing. Lastly, the novels and poetry are indicative of the need for distraction.

Chapbooks (cheap, printed pamphlets on a variety of topics) were also found in the colony’s homes. Intended primarily for the working class, they included primers and almanacs. Even their titles have often failed to survive, but those that do indicate topics ranging from education to religion, entertainment, gardening and medicinal preparations.

Among the more formal books, about forty were penned by authors who were anti-establishment to varying degrees. The principal works of the major French Jansenists — Arnauld, Nicole and Pascal — circulated here. Even titles that were placed on the Index of forbidden books by Rome or Paris could be found. Political satire, however, was censured by the State, while certain works of skepticism provoked the wrath of the Church. Fénélon’s Télémaque and Montaigne’s Essais are the best examples of this. A few other books that were not on the Index questioned certain values espoused by France’s religious and political authorities at the time. Two tendencies characterize this nonconformist literature. One is political and social criticism tinged with skepticism or rationalism, found in the works of authors such as Bayle, Desperriers , Erasmus, Gacon, Le Vayer, Vauban and Voltaire. The other is the libertine content and Epicurean philosophy that characterizes the works of Chaulieu, Charron, Gassendi, Patin and Saint-Évremont. Such unorthodox literature appealed mainly to people in positions of power, who were usually quite influential.

Drinking Establishments and Inns (show)

On September 19, 1648, the Communauté des Habitants granted Jacques Boisdon the exclusive right to open a pastry shop and hostelry (inn) in Québec. The history of innkeeping in New France thus begins with Boisdon, who has a colourful surname or nickname (which could be read as “bois donc”, meaning “have a drink”). His establishment, located in the public square near Québec’s church, provided accommodation in exchange for payment, a new idea at the time. In the dictionary Furetière published in 1690, the word hostelry is defined as “a furnished establishment kept by a hosteller that provides lodging and meals to travellers and other paying guests”. The word hosteller is defined as someone “who keeps an establishment with furniture and provisions, an inn or a cabaret that offers accommodation and meals to travellers or people with no fixed address”. A cabaret, according to Furetière, was something like a modern liquor store, and a tavern was a place that offered food and drink to be consumed on the premises. Therefore, inns, cabarets and taverns were all places where people were received, found distraction and could socialize.

Québec, a port city and capital of New France, had many inns. Montréal, a frontier and garrison town, where fur trade voyageurs came and went, and Louisbourg, a fortified town inhabited by fishermen and soldiers, also had many establishments that offered accommodation. The signs on the inns and taverns, like “Ville de la Rochelle” on Jean Maheu’s establishment and “Signe de la Croix” on Laurent Normandin’s, certainly attracted the civilian residents of Québec, but even more so sailors and soldiers. Jean Seigneur’s “Épée Royale” and Germain Maujot’s “Autel de la Marine” played the same role in Louisbourg.

Where were drinking establishments located in Canada?

Archival records show that there were at least 262 owners or managers of inns in Québec between 1648 and 1760. About two-thirds of them owned a tavern before they opened an inn. The city had no shortage of this type of establishment, it seems, since there was one innkeeper or tavern owner for every 100 to 130 inhabitants between 1716 and 1744. Of those establishments, 25 to 34 were permanent, even though the population grew from 2,573 to 5,027 people over the same period. Montréal, Trois-Rivières, Louisbourg and New Orleans also had establishments that offered accommodation. Outside the towns, each village had an inn or a tavern to receive voyageurs who arrived by canoe or habitants who attended mass in the parish. Lachine, the departure point for all voyageurs going to the Pays-d’en-Haut, had two or three such establishments. In addition, all the forts had a canteen where soldiers could buy tobacco and drinks. With the exception of the signs required by law, from the exterior it was not possible to distinguish inns from residences. Most had outbuildings, sheds and gardens. In 1745, Claude Morillonnet, known as Berry, rented innkeeper Louis Leroux a house in the Faubourg Saint-Louis and “a vide bouteille in the garden, with a table and benches, all made of wood”. A vide bouteille was an isolated location, a sheltered area or a small house where people could get together to relax or drink. It may have been one of the first outdoor cafés in the city of Québec!

These meeting places — inns and taverns — were usually an integral part of their owners’ homes. They were not like twentieth-century hotels. Since most of the innkeepers and tavern owners purchased or rented only one house, that is where their commercial activities took place, and they often receiving their clients in the kitchen.

Innkeepers and Tavern Owners

Since the inn was located in the home — the family kitchen being the centre of activity — every member of the family helped out, especially the innkeeper’s wife. Although the husband usually held the licence, the wife was always a precious collaborator and was often the one who managed the business. In Québec and Louisbourg, 10% to 15% of the innkeepers were women. In Montréal, the percentage of female innkeepers was somewhat lower. Several women took over the business when their husbands died, and others ran the business while their husbands worked elsewhere. For many people, the inn provided supplementary income. Unlike work performed outside the home, in a workshop or store, innkeeping appears to have been a real family business.

Judging by the number of professions that Québec’s innkeepers and tavern owners claimed to engage in, there were few professional innkeepers. Almost three-quarters of them practised or had practised another profession. In fact, it does not seem to have been too difficult to learn the trade, since people of various occupations, such as shoemakers, public servants and carpenters, could become innkeepers or tavern owners overnight.

Regulations

The large number of drinking establishments in New France reveals that Canadians were quite partial to drink. The numerous pastoral letters issued by the bishop and extensive preaching by the clergy against the sale of alcohol support this observation.

Between 1663 and 1749, 34 sets of regulations and ordinances were promulgated for the principal centres: Québec, Montréal and Louisbourg. About 15 general regulations dealt specifically with innkeeping, and 14 ordinances were aimed at specific groups, such as soldiers and shipyard workers. The most common regulation dealt with the obligation to obtain written permission to operate a cabaret. Some restrictions were reiterated on numerous occasions: the sale of alcohol after certain hours in the evening and during religious services, and the purchase of provisions in the market as soon as it opened, no doubt to prevent innkeepers from buying all the food before everyone else arrived. An ordinance issued in 1726 by Intendant Dupuy was so strict that the French authorities denounced it a few years later.

Despite the myriad regulations, records show only about thirty violations in the city of Québec, three-quarters of them related to taverns without signs. The other people who violated the regulations had sold alcoholic beverages during religious services, tolerated drunkenness in their establishments and “served wine” outside business hours. Only three liquor licences were revoked. In Montréal, fines were primarily related to the ban on the sale of alcohol (other than beer and cider) to Aboriginal people.

Louisiana authorities also had to deal severely with non-compliance in the innkeeping business. In the 1720s, or thereabouts, the colony’s attorney general, François Fleuriau, inspected the taverns in New Orleans to ensure that they closed during church services on Sundays and feast days. In 1751, in passing the Règlement sur la police des cabarets, des esclaves, des marchés en Louisiane (Regulations concerning the policing of taverns, slaves and markets in Louisiana), Governor Vaudreuil was reacting to the “disorder that [had] increased in the city as a result of the large number of taverns that [had] been established without permission”. From then on, only six tavern owners were allowed to maintain their operations in New Orleans, and they were not allowed to serve soldiers, who had to use the canteens. The regulations state: “Everyone shall drink in the place reserved for them.” The ban on the sale of alcohol to Aboriginal people and slaves was also reiterated.

Court records reveal a long list of problems caused by the presence of numerous inns in the main centres, including swearing and blasphemous remarks heard in the streets, absenteeism in the workplace and delayed work, salaries spent in taverns by husbands or wives, premeditated theft, arguments and fights, a few duels, and even the murder of a tavern owner by a drunken client.

In spite of their reputation as places of debauchery, there is no evidence that taverns were connected with prostitution. Some intoxicated clients did insult female innkeepers by calling them names associated with prostitution, and some well-known women did not hesitate to sell their charms. A woman named Saint-Michel, in Lachine, and one named Lamarque, in Montréal, for example, were both active in the 1680s, but they were exceptions.

What did people eat at the inns?

It is not easy to reproduce the menus of the inns and taverns. It is in fact difficult to get an overview of the meals served at the time, due to a lack of information. Around 1700, innkeeper Charles Trépagny, of Québec, charged 10 sols for breakfast, 1 livre and 10 sols for lunch, and 15 sols for dinner. Lunch was the main meal of the day, but alcoholic beverages were consumed with all three: eau de vie in the morning, and wine at noon and in the evening. The information available on the types of meals served shows that omelettes and eel were favourites. They were no doubt served on meatless days. Innkeepers also prepared stews, chicken, young pigeon, partridge, lamb and veal loin. Innkeeper Nicolas Blain proposed cheeses from Holland and Gruyère on his menu, and a cook named Leclerc made cakes at Laborde’s tavern in the late seventeenth century. Inns also offered snacks, and sold fruit and desserts.

Games of Skill and Chance (show)

Outings in horse-drawn carriages in the summer and in sleighs in the winter, as well as skating and sleigh races on the ice, were outdoor activities that enlivened the lives of most of the inhabitants of New France. Parlour games were also enjoyed by everyone, but balls were reserved for the elite. Some pastimes were more original and unusual, like the “jeu de Bagues” (ring game), played on a fairly imposing structure weighing about two hundred pounds, located in the backyard of one of Louisbourg’s residents. It consisted of a machine that turned on a pivot like a merry-go-round, with seats and wooden horses on which players sat. Each player had a stick and, as the machine went around, they inserted the stick into rings hanging from a pole and removed them. This game of skill was an exception, however; billiards, skittles, cards and dice were much more common in the colony.

Billiards

Billiards was a popular form of entertainment in all towns in New France. For a long time, it was played only by the aristocracy, but the various versions of it — all fairly different from modern billiards — became widespread in France in the eighteenth century. In the colony, billiard tables were found primarily in urban inns and taverns. One of the first establishments to offer billiards to its clients was Abraham Bouat’s inn, which was located on Rue Notre-Dame in Montréal, near the parish church, and was in operation the last 25 years of the seventeenth century. In Québec, at least 12 innkeepers had billiard tables between 1690 and 1760, but only two or three were permanent. Louisbourg and New Orleans also had a few billiard tables.

A description of a billiard set acquired by Pierre Petitot Desmaret for 400 livres in 1743 provides a good idea of what they were like at the time: “a billiard table about 12 feet long and about 6 feet wide with a worn covering and Beaufort canvas under the covering, just like in the sellers’ homes, three pairs of new billiard balls and four old ones, 26 cues with sleeves, eight tips, ten tin hanging lights with holders and two large benches”. Innkeepers who offered billiards must have needed a lot of space to set up the table and accommodate players and spectators. When Jacqueline Deleau, widow of Jean-Pierre Daubigny, rented a house on Rue Saint-Pierre, in Québec’s Lower Town, in 1714, the “Lessor had to raise the partition in the third-floor room to accommodate the said tenant’s billiard table and had to have a suitable window set in the said partition to let in light”.

Billiards was a game for two or four players, and there were often several spectators, who would referee disputed shots, if necessary. The following account by market seller Jean Taché, dating from 1739, provides a good example. He had gone to Pierre Petitot’s “to play a game, as he did every day with his friends” and, after a difficult shot, “the owner of the establishment counted the votes of the gallery, which consisted of twelve to fifteen people”. Even if everyone had access to billiards, the game was not played at every level of society. Thirty-one people, including three women, owed money to an innkeeper named Bachelier for billiard games, and they were all officers, public servants, merchants or professionals.

Skittles

The game of skittles played in New France was different from today’s. The rules are not known, but the number of pins (three to nine) was not the same, and the ball could be rolled, as is done today, or thrown, as in pétanque. It was usually played outdoors. In 1748, Chevalier de La Corne, of Montréal, acquired a skittles set that had belonged to the former governor of Trois-Rivières, Claude-Michel Bégon. It included a ball and eight small wooden skittles.

Skittles was not reserved for the elite; on the contrary, everyone enjoyed it, young and old, domestics and artisans. As early as 1674, Grégoire Simon and Pierre Mathieu played skittles around 5 p.m. on Sundays at Pointe-aux-Trembles, in front of a house occupied by a man named Saint-Ange. However, there were sometimes misunderstandings that led to fights. When that happened, the skittles could be turned into blunt weapons and become dangerous. Trial records show that, in 1688, an habitant hit a soldier over the head with a skittle.

The exact number of skittle sets in the colony is not known, but some inns and taverns offered skittles and boules. Caterer and innkeeper François Marseau, of Québec, an associate of another innkeeper, Daniel Rietmann, owned a skittles set. Tavern owner René Daniau, also of Québec, had a playing surface for boules in his yard, on Rue Saint-Jean. In Louisbourg, merchant Jean Pierre Grégoire also had a skittles set.

Dice and Cards

While all games of chance were banned from time to time in inns and taverns, dice and card games remained very popular under the French regime. In Québec and Montréal, quarrels in the inns and taverns led to numerous trials, and the records mention that clients played games of chance. That was also the case in Louisbourg. Card games were also played in rural areas. A surgeon named Bertier, from Québec, sold two dozen cards for playing piquet to J.-F. Duchesny, who lived in Sainte-Anne, near Batiscan.

According to Antoine de Furetière, a famous lexicographer of the late seventeenth century, many people played piquet in New France. The best-known card game, it was played with 36 cards in the seventeenth century and 32 in the eighteenth. Cheating was common as well. In 1714, Jean-Baptiste Alleou, of Saint-Étienne, and Mr. De Chalus, a company captain, played piquet at the Grand Air Inn. Alleou insisted on ending the game because he had no money left, but, for some reason, he continued to play until four o’clock in the morning. In the end, Chalus claimed to have won a considerable sum, 300 livres, which was roughly the equivalent of an artisan’s annual income. The other card games mentioned in court records include lansquenet, brelan (three of a kind), mouche, trut, romestre (also called romilly) and triomphe (triumph).

The Académie des jeux

Under the Ancien Régime in France, game rules were standardized as books on the subject became available. La Maison académique, recueil général de tous les jeux divertissans pour se réjouyr agréablement dans les bonnes compagnies (La Maison académique, a full collection of games to be enjoyed in good company) was published in 1654. It includes the rules of piquet, trictrac (an old form of backgammon), billiards and oie, and was updated and reprinted several times. The 1718 edition bears the title Académie universelle des jeux and was printed in Paris by Nicolas Le Gras. That edition was reprinted no less than 25 times before 1800. Estate inventories show that at least three copies of the work crossed the Atlantic. One belonged to an attorney general, one to a merchant and the third to an officer.

The rules of piquet, lansquenet, brelan (three of a kind), mouche, trut, romestre (also called romilly) and triomphe (triumph) are available in the electronic editions of the Académie universelle des jeux, found on the following website: http://www.archive.org/stream/acadmieuniverse00unkngoog#page/n5/mode/2up

Contemporary publications offer simplified explanations of different versions of some of these games in modern French.

Dice games were also popular, and players sometimes lost significant sums. In 1677, Charles Catignon, Keeper of the Royal Stores, played dice with the Sieur de Repentigny and lost 756 livres in a single day. Trictrac (an old form of backgammon), with dice, cups, ivory pieces and ebony boards, was also played in New France. Records show that, in May 1726, after eating a game stew, a group of four or five people spent the evening playing “trique” in a Louisbourg establishment belonging to a man called Lahaye. However, that was not common practice; people did not play trictrac, quadrille or chess in inns and taverns. The nine trictrac sets listed in New France inventories all belonged to public administrators, including Governor Philippe de Vaudreuil.

Based on estate inventories, this type of entertainment seems to have been enjoyed only by administrators and professionals. It is interesting to note that quadrille (or jeu de l’hombre), a game with its own set of cards usually played by four people in a quiet setting, appears to have been an old form of bridge. As for chess, inventories show that only three people owned this type of game: Louis de Norey, who was a member of a religious order, Attorney General Guillaume Verrier and fur merchant Noël Noël. Claude Barolet, a Louisbourg merchant, owned a set of dominos.

Conclusion (show)

New France’s inns and taverns, where people were received, found distraction and could enjoy the company of others, were ideal places for socializing. Drawn by signs that usually stood out clearly on the façades of the houses, residents who sought company or refreshment found what they needed there. So did travellers in search of temporary accommodation. Everything was offered: meals, snacks, cider, beer and other alcoholic beverages, and games of skill and chance. Everyone could go there to escape the monotony of daily life.

Often gathered together for work or pleasure, clients met new people, exchanged the latest news, teased each other and sometimes even fought when they had had too much to drink. However, the inhabitants of the colonies did not need to sit at a table in an inn to amuse themselves; they could play games of skill outdoors. Other forms of recreation, such as reading, music and theatre, required a quieter setting where one could concentrate, something rarely found in the inns and taverns.

It was most often out of professional or religious necessity that the inhabitants of the colonies took up pastimes such as reading, music, dance and theatre, while taking into account the restrictions imposed by the Church.

Suggested readings (show)

Bacqueville de la Potherie, Claude-Charles Le Roy, known as. Histoire de l’Amérique septentrionale. Vol. 1. Paris: Brocas, 1753, pp. 278–279.

Briand, Yves. Auberges et cabarets de Montréal (1680-1759): lieux de sociabilité. Master’s thesis, Université Laval, 1999.

Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Biographies published in volumes I to III. Quebec City: Presses de l’Université Laval.

Ferland, Catherine. Bacchus en Canada: boissons, buveurs et ivresses en Nouvelle-France. Quebec City: Septentrion, 2010.

Ferland, Catherine. “Le nectar et l’ambroisie : la consommation des boissons alcooliques chez l’élite de la Nouvelle-France”. Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, vol. 58, no. 4 (spring 2005), pp. 475–505.

Furetière, Antoine de. Le Dictionnaire universel. 3 vols. The Hague, Rotterdam, 1690. Entries for auberge, cabaret, hôtelier, hôtellerie, taverne.

Gallat-Morin, Élisabeth. “La musique dans les rues de la Nouvelle-France”. Les cahiers de la société québécoise de recherche en musique, vol. 5, nos. 1–2, pp. 45–51.

Gallat-Morin, Élisabeth and Jean-Pierre Pinson. La vie musicale en Nouvelle-France. Quebec City: Septentrion, 2003.

Laflamme, Jean. L’Église et le théâtre au Québec. Montreal: Fides, 1979.

Proulx, Gilles. Aubergistes et cabaretiers de Louisbourg. Parks Canada, MRS 136, 1972.

Proulx, Gilles. Les bibliothèques de Louisbourg. Parks Canada, MRS 271, 1974.

Proulx, Gilles. Tribunaux et lois de Louisbourg. Parks Canada, MRS 303, 1975.

Séguin, Robert-Lionel. Les divertissements en Nouvelle-France. Bulletin no. 227. Ottawa: National Museum of Canada, 1968.

Voyer, Simonne. La danse traditionnelle dans l’est du Canada. Quebec City: Presses de l’Université Laval, 1986.

On the Internet

![Jean Berger’s insulting verses | Procès entre Claude de Saint-Olive, apothicaire, plaignant , et Lambert Thuret dit Prévost, caporal de la Compagnie d'Esgly, Jean Berger, peintre, et Latour, soldat de la Compagnie d'Esgly, accusés d'agression [extrait]. (Trial between Claude de Saint Olive and Lambert Thuret, Jean Berger and Latour) June 19, 1709, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, Direction du Centre d'archives de Montréal, Fonds Juridiction royale de Montréal, TL4, S1, D1148 Jean Berger’s insulting verses](https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/files/2011/11/New-France_5_2_1_Jean-Berger’s-insulting-verses_1-219x300.jpg)

![Jean Berger’s insulting verses | Procès entre Claude de Saint-Olive, apothicaire, plaignant , et Lambert Thuret dit Prévost, caporal de la Compagnie d'Esgly, Jean Berger, peintre, et Latour, soldat de la Compagnie d'Esgly, accusés d'agression [extrait]. (Trial between Claude de Saint Olive and Lambert Thuret, Jean Berger and Latour) June 19, 1709, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, Direction du Centre d'archives de Montréal, Fonds Juridiction royale de Montréal, TL4, S1, D1148 Jean Berger’s insulting verses](https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/files/2011/11/New-France_5_2_1_Jean-Berger’s-insulting-verses_2-225x152.jpg)