-

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

- The Explorers

- Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

- Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Economic Activities

- Population

- Daily Life

- Heritage

- Useful links

- Credits

Colonies and Empires

Governance and Sites of Power

In New France, as in Ancien Régime France, the monarch, and not the people, held sovereign power. From Paris and their chateaux in the countryside, the kings of France and their entourage, depending on the circumstances, took a more or less keen interest in the colonies. In the beginning, they simply delegated administration to trading companies. However, during the last third of the 17th century, the crown took over the administration of the colony, instituting tighter control and stability.

From then on, the various colonies came under the authority of the Minister of the Navy and his clerks at Versailles. On the other side of the Atlantic, at Québec, the governor and the intendant shared the tasks of senior administration. The Superior Council, together with minor civil servants, and in the rural parishes, militia officers, took part in the administration of Canada. With the founding of Louisiana and Île Royale, more new governments were established which would require the creation of parallel structures.

The following text from Marie-Ève Ouellet presents a portrait of the colonial administration, describing its structure and the way it worked. It demonstrates how systems of governance evolved over time and, depending on the region, how the territory of New France proved to be a land of experimentation for the crown. It also shows how the absolute nature of royal power was mitigated in practice.

Introduction (show)

As it colonized New France, France transplanted its form of government: absolute monarchy. The king was the source of all justice and exercised supreme power by divine right. Like France, New France was an old order society that had an elitist, hierarchical vision of itself. Since the king was the source of all power, relationships of subordination created a stream of loyalties that bound the monarch to the humblest of his subjects. This power was not unlimited, however, for it was tempered by the inability of the monarchy to impose its law on a remote, immense territory like New France. Although it adapted to the colonial context, the administration of New France was modeled on that of the provinces of France. This power structure should not be confused with the seigneurial system, which was a mode of granting and distributing land, rather than a political system. While land ownership and the seigneur’s privileges created a relationship in which the seigneur dominated his tenants, the title of seigneur did not entail any particular political power.

The reign of the monopoly companies (show)

In the early 17th century, the king did not yet directly govern his colonies. Instead, they were administered by companies that secured a trade monopoly over a given territory in exchange for an annual royalty and an obligation to establish a settlement. The idea was not specific to New France. It drew on practices in use in other European countries, notably Holland. Following the successive failures of many private companies in French North America, Cardinal Richelieu, principal minister of King Louis XIII, founded the Compagnie des Cent-Associés in 1627. The new company acquired seigneurial rights over New France, perceived at the time as an immense territory extending from Newfoundland to the Great Lakes and from Florida to the North Pole. In exchange for the fur trade monopoly, among other things, the Company committed to establishing 4 000 Catholic settlers in the colony within 15 years and to converting the aboriginal peoples to Catholicism. In 1627, the population of Canada (i.e. the St. Lawrence Valley) scarcely numbered one hundred inhabitants. Beginning in the era of the Cent-Associés, the king would appoint a governor to represent him in New France, just as he did in the provinces of the home country. The task of the early governors was to maintain order and to protect the settlers and the territory. They possessed extensive powers to do so. As the highest civil and military authority, the governor acted as legislator, judge and administrator and he could enact ordinances and try offenders. As military commander, he was tasked with defending the colony and maintaining diplomatic relations with the First Nations. Lastly, he was responsible for the management of the territory and granting seigneuries. Sole master of the country, the governor relied on a rudimentary administration comprising a few civil servants. During the regime of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, the governors had the difficult task of reconciling the interests of the company with those of the king. The fur trade was so unprofitable it could barely meet the needs of the colony. The situation was complicated during the 1650s by the destruction of Huronia, which dismantled the French trading network and caused fur supplies to dwindle. Frequent wars generated insecurity and political instability. Between 1636, the year of the arrival of the first governor, Charles Jacques Huault de Montmagny, and 1663, five governors held office, and the most influential settlers of the colony defied the Compagnie des Cent-Associés. For the king, it became obvious that the colony needed a higher authority to balance the divergent interests of merchants, colonizers and missionaries.

A royal colony (show)

The year 1663 was a pivotal year in the history of governance in New France. The young king Louis XIV demanded that the Compagnie des Cent-Associés relinquish its position because it had proven unable to administer the colony and had not honoured its obligation to colonize the settlement. As Louis XIV declared, using the royal “we” and in the convoluted administrative language of the time: “We hereby order, will, and may be pleased that all rights related to property, justice and seigneurial tenure, to the appointment of governor and lieutenant generals in the said countries and towns, even to appoint officers who shall render sovereign, become and hereafter remain a responsibility of our Crown.” (Actes du pouvoir souverain, 1663, cited by Jacques Mathieu, La Nouvelle France. Les Français en Amérique du Nord xviie-xviiie siècles, p. 103 [translation]).

In taking this action, Louis XIV repatriated the colony to the Domaine du roi (or King’s Domain) and made himself personally responsible for its administration. Until the end of the French Regime, there would be other trading companies in New France, but they would no longer be obligated to see to its settlement or to the remuneration of governors and administrators, as had been the case under the Cent-Associés. Following Louis XIV’s royal takeover of New France, institutions were established there that would ensure that the monarchy could exercise as direct a control as possible over these new lands.

Absolutist centralization (show)

The reforms instituted in New France starting in 1663 occurred in the context of centralization that characterized the absolute monarchy of Louis XIV. During his childhood, the latter was marked bythe events of the civil war known as La Fronde (1648-1652), when the old noble families and the parliament of Paris rose up against the crown. Acceding to the throne in 1661, Louis XIV went to great lengths to strip the old nobility of its political powers. He gradually weakened provincial institutions, including the parlements which acted as regional regulatory bodies and courts of appeal throughout France, to the benefit of a centralized administration comprised of civil servants who would execute his orders and who were only accountable to him.

The Intendant

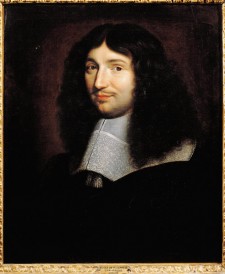

One of the major changes was the importance acquired by the secretaries of State, whose functions were clarified under Louis XIV. In the absence of prime ministers, they administered the kingdom and made most of the decisions, on their own or in agreement with the king. New France was placed under the jurisdiction of the Ministère de la Marine or Ministry of the Navy, which centralized the administration of all the colonies. The centralization of decision-making at Versailles was matched by the centralization of the provincial administration through the appointment of intendants. Until the mid-17th century, the king’s representatives in the provinces of France were officers of finance, officers of the law, soldiers or commissioners sent on temporary missions. Over the following decades, the king established the permanent position of intendant in each of the provinces, and fill it with men tasked with transmitting and applying the king’s orders and reporting back. The intendants thus played an intermediary role between central power and the local level.Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683), controller general of finance and secretary of state

Under the reign of Louis XIV, six influential persons are assisting the king in the administration of the kingdom: the Chancellor, the controller general of finance and secretary of state for foreign affairs, war, home of the King (head of the court and of Paris) and Navy. The controller general function is a key position, similar to that of the interior ministry, since it is responsible for finances and the appointment of intendants of the provinces. The position was created in 1665 for Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who combined this function with the Department of the Navy, where he was not only responsible for the colonies, but also for all the internal and external trade. The power of this character close to the king and his interest in colonial affairs explain the significant efforts made by the monarchy during the 3rd third of the 17th century to reform the administration, stimulate the economy and send immigrants to New France.

The same model was applied in New France starting in 1663 with the appointment of the first intendant: Louis Robert de Fortel. He never did journey to the colony, however, so the history of Canadian intendancy really began with Jean Talon, who landed at Québec in 1665. A former intendant of the French province of Hainaut, Talon was given the title of “Intendant of Justice, Police and Finances of Canada, Acadia and Newfoundland”. His responsibilities were as numerous as they were varied. In the field of justice, he was the “eye and hand of the king,” the king having delegated to him the power of rendering justice in the monarch’s name. He presided over the Sovereign Council, the court of last instance which will be discussed below, issued decrees called ordonnances (ordinances) and oversaw the application of laws. The intendant was also responsible for police, a term whose meaning differs from our contemporary definition and instead refers to general administration. The work of the intendant in this field included sanitation, health, public security, roadways and fire prevention. In addition, the intendant had vast financial responsibilities. He managed the budget, controlled spending (including military spending) and fixed currency rates and the price of commodities (wheat, meat). He was responsible for supplying the king’s stores, where a variety of merchandise was stocked, including tools, arms, munitions and construction materials. In more general terms, the intendant supervised the colony’s socio-economic development and took measures to promote settlement and the growth of agriculture, commerce, fisheries and industry. The intendant’s task thus encompassed all aspects of administration, which in fact made him the person most conversant with the colony’s internal affairs. As with the governor, however, the considerable extent of the intendant’s powers did not make him all-powerful. The intendant was subject to the directives issued by the king and his ministers, and he had to secure their approval for anything that diverged from day-to-day administration. If difficulties arose, he could be dismissed at the king’s pleasure.

The Sovereign Council

The year 1663 also marked the founding of the Sovereign Council of New France, a court of appeal for civil and criminal matters.It was granted extensive legislative and judicial powers. It regulated all general and municipal police affairs, including the maintenance of order, public security, supply and services for towns, as well as control over spending. Over time, the number of councillors varied, but never exceeded twelve persons, including the governor, the intendant and the bishop. The Sovereign Council sat at Québec, but during the 18th century, similar councils would be established in Louisiana and Île Royale.

The operations of the Sovereign Council of New France were similar to those of provincial parliaments France. In contrast to the English parliament, whose role was political, the French parliament of the Ancien Régime played an essentially judicial role. Above all, it was a court of appeal. In principle, parliaments did not participate in legislative power but, in practice, they intervened through the right to register ordinances. What did registration entail? It was an act that rendered a decision and its application official. To have the force of law in France, an ordinance had to be published at a sitting of parliament and transcribed in specific registers. The councillors of parliament then validated the legality and fairness of the ordinance and if they had any remonstrances to formulate, they could address them to the king. Similarly, in New France, the registration of ordinances and the king’s decrees by the Council gave them the force of law. Because the colony was remote, the Sovereign Council of New France had up to one year to exercise its right of remonstrance with regard to royal decisions. Yet this power proved short-lived because as early as 1673, a royal declaration withdrew the right of remonstrance from French parliaments. The Sovereign Council of New France thus lost its power to scrutinize legislation and was reduced to registering and applying it. The king’s intent to weaken the power of the colonial Council was confirmed in 1702 when it was renamed “superior,” instead of “sovereign,” as was the case for the parliaments of France. The Superior Council also lost its prerogatives with respect to the registration of ordinances, and was henceforth required to receive the governor and the intendant’s approval before registering them. In the 18thcentury, the Superior Council became nothing more than a court of appeal for civil and criminal matters. Confined to the role of carrying out the decisions of the governor and the intendant, it lost its influence over colonial policy. The position of councillor on the Council nevertheless continued to carry a measure of prestige. It was accordingly coveted by members of the colonial society’s elite, for whom being in the service of the king offered a way of gaining renown.

The Governor

The creation of the Sovereign Council and the position of intendant in New France in the 1660s considerably reduced the responsibilities of the governor general, who had formerly held all legislative, judicial and military powers. After 1663, responsibility for the military remained the main prerogative of the governor. As a military commander-in-chief, the governor general had direct, supreme command of the regular troops and the militia in the colony. Certain governors personally led campaigns against the Iroquois in the 17th century. Diplomacy with Native peoples, as well as exploration, were also within the purview of the governor. Although the governor may appear to to have held fewer responsibilities than the intendant, his role as the king’s personal representative nevertheless placed him at the pinnacle of the colony’s hierarchy. A prominent figure, the governor held the rank of lieutenant general in the royal armies and enjoyed the ceremonial privileges of a French field marshal. He occupied a place of honour during Mass at the cathedral, had a private company of guards, and always travelled with an entourage of officers and footmen to the sound of drums. In the colony, his word was law.Relationship between the governor and the intendant (show)

We have seen that the Sovereign Council was gradually dispossessed of its political functions. In New France, it was the governor and the intendant who governed, which inspired historians to speak of a two-headed government. Indeed, the relationship between the two leaders was at the heart of colonial political life. The governor was the king’s personal representative in the colony, whereas the intendant carried out the king’s policies and ensured the laws were applied. With the exception of the last, Pierre François de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal, who was born in Canada, the governors were always French-born men, recruited from the old noblesse d’épée (“nobility of the sword”). Those who were appointed to New France were also career officers who had been in the metropolitan army, the navy or the colonial troops. The intendants of Canada were also all Frenchmen, but of the noblesse de robe (“nobility of the gown”), a more recent aristocracy of legal culture and dedicated to the service of the king. While the position of governor crowned a long military career, that of intendant usually represented a colonial digression that allowed the holder to aspire to promotion in the home country. Some intendants nevertheless held long terms of office, the record belonging to Gilles Hocquart who spent some twenty years in the colony between 1729 and 1748. The differences in rank and function explain the governor’s hierarchical pre-eminence over the intendant. This was particularly visible during processions, which the governor would always lead. Since New France was an old order society, and thus particularly sensitive to hierarchy, the precedence of the governor over the intendant was a source of conflicts that the king sometimes had to mediate.

Conflicts and the obligation to collaborate

Historians have long emphasized the conflicts between the governor and the intendant, obscuring the fact that they usually worked together in performing their duties. The two leaders were required to draft a joint annual report to the king on the state of the colony. They shared many areas of responsibility, including the granting of seigneuries, the regulation of the trade of fur and spirits, and the establishment of commodity prices and seigneurial rights. In emergencies, times of war or famine, the governor and the intendant could not always wait for directives from Versailles before taking action. They had to make shared decisions for the good of the colony. Despite the obligation to collaborate, conflicts arose because of unclear boundaries between their respective responsibilities. The main issue involved the governor’s spending powers and the intendant’s responsibility for monitoring the budget. The governor could, for example, order work on fortifications even if the intendant deemed available funding to be inadequate. Or, since the fur trade in New France was closely tied to diplomacy with Native peoples, the governor sometimes claimed prerogatives in trade that encroached upon those of the intendant. In the late 17th century, at the request of both the governor and the intendant, the Ministry of the Navy issued a new regulation clarifying the respective responsibilities of the two positions. Although this did not protect the colony against personality clashes between the men who occupied them, it at least prevented the types of conflict that had paralyzed colonial political life at certain periods in the 17thcentury.

Clientelism and patronage: two networks of power

The governor and the intendant did much more than merely implement royal policies. Through their knowledge of the local context, they exercised considerable influence on the Minister and inspired—even suggested—a great many of his policies. The situation was similar in the provinces of France. There the king frequently solicited the opinion of the intendant before making a decision on local issues. Since the monarchy granted titles of nobility, seigneuries and most contracts and positions in the army and in the administration, the monarchy’s representatives in the colony—the governor and the intendant—had considerable influence on colonial society. Indeed, in an Ancien Régime society like that of New France, personal success did not merely depend on wealth or education, but also—and above all—on the ability to gain favours from the authorities. The colonial authorities’ opinion about an individual could be a source of privilege or disgrace. Through their power to make recommendations and grant favours, the intendant and the governor could gather a clientele of courtiers in their respective fields of intervention. Thus, the governor general would recommend candidates to the king to fill vacant positions in the army. Such positions were highly coveted because officers appointed to forts and trading posts in the interior of the continent could acquire wealth by trading with Aboriginal peoples. The intendant was not to be outdone, however, and his jurisdiction over colonial finance won him supporters attracted by government contracts.Québec, capital of New France (show)

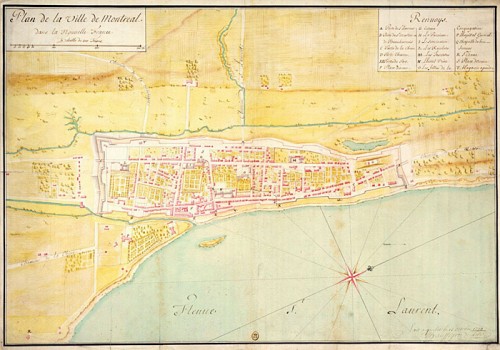

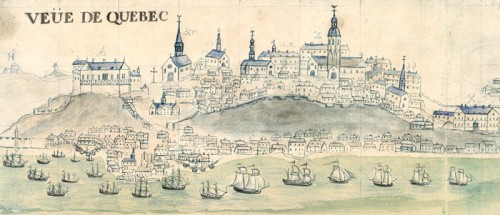

Most administrative and religious institutions were based at Québec, the capital of the colony. It was the seat of the governor general, the intendant, the Sovereign Council as well asthe bishop. It was also the seat of other officeholders, notably the treasurer general, the grand voyer (chief road inspector), the officers of the admiralty and the provost. While Québec was the official political seat of the colony, it was not the sole seat of power. In summer, the governor and the intendant set up offices in Montréal to receive First Nations ambassadors from the interior and to manage affairs concerning trade and commerce. Returning to Québec in the fall, they would draft official correspondence with Versailles in time for the departure of the last ships before winter. The same process occurred in Louisiana during summer, while the town governor left the capital of New Orleans to meet with his Aboriginal allies in Mobile.

The Château Saint-Louis

The official residence of the governor general, political heart of the capital, was known as the Château Saint-Louis. It was kept under constant surveillance by a military guard, a symbol of the governor’s rank and power. It was the centre of the colony’s diplomatic operations, and from there that the governor and his staff conducted a voluminous official correspondence with the court at Versailles. It was at Château Saint-Louis that the seigneurs had to swear fealty and pay homage to the king, before the governor and the intendant, to be allowed to take possession of their seigneurie. The Château was at the centre of the city’s high society and the site of many banquets, receptions and plays held by the governor. The Château’s predecessor was Fort Saint-Louis, built on the heights of Québec in the 1620s under the administration of Samuel de Champlain. A modest wooden compound at first, it was soon replaced by a stone fort to protect the inhabitants from potential attacks on Québec. After the death of Champlain, his successor Huault de Montmagny replaced this fort with a massive stone building that would become the first Château Saint-Louis and house the governors until the arrival of governor Louis de Buade de Frontenac in 1672. The latter expanded and renovated the building, before levelling it and replacing it with an imposing two-storey structure during the 1690s. Construction work on the site continued until 1723, when the west wing was completed. By means of these ongoing and costly additions and renovations, the governors aimed to create a reflection of the splendour and prestige of their position. The political and military functions of Château Saint-Louis survived the Conquest, as British governors used the building as a residence until it was destroyed by fire in 1834.

The Château St. Louis, detail of the View of Quebec and figurative map of swift help sent…to the King’s ship the Elephant, Mahier, 1729

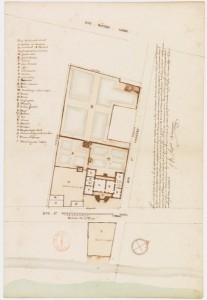

The Intendant’s Palace

It was not until the 1680s that the intendant occupied an official residence. Earlier, the intendants lived in a house located beside the Séminaire de Québec, in the most eastern part of upper town. In 1686, the king acquired intendant Jean Talon’s former brewery, located in the lower town, on the right bank of the Rivière Saint-Charles. The brewery, closed since 1675 and rented by the king to store merchandise, was renovated and expanded to house future intendants and to centralize all the functions of intendancy under the same roof. A room was fitted out to host the sessions of the Sovereign Council, which had formerly met at the Château Saint-Louis in the governor’s antechamber. The building would later house a suite for the intendant, a chapel, a court for the provost, a library, the king’s stores, a prison and a dwelling for the jailer and his family. Fire ravaged the Intendant’s Palace twice, in 1713 and in 1725. But each time, the metropolitan authorities took advantage of the opportunity to construct a building of much grander scale. The Palace of 1726 had the appearance of a veritable château with its two storeys, monumental entrance and vast gardens. Like the governor’s own Château Saint-Louis, the Palace was one of the tools with which the intendant exercised his authority and asserted his prestige, notably during the receptions he hosted for Québec’s high society. Upon the Conquest, the Intendant’s Palace was used to lodge British troops. It was destroyed during the attempted American invasion of 1775.

Ceremonies and power

The architectural splendour of public buildings was intended to reflect the grandeur of the French monarchy. Grandeur was also embodied in the public ceremonies that took place in colonial cities. Processions, in which each member of the elite occupied a place according to his position, enabled the people to observe the importance of the hierarchy. Key events in the life of the monarch, and the ascent of a new one, were occasions for ceremonies of exceptional scope. The arrival of a new governor general at Québec was similarly underscored by an elaborate ceremonial that included speeches, a review of the troops and an official meeting with the representatives of the various groups of society (officers, magistrates, religious orders), all accompanied by gun salvos. In 1730, major celebrations were organized at Québec and at Louisbourg to honour the birth of the son of Louis XV. The festivities were spread over more than a month and comprised many masses, processions, fireworks, illuminations, dinners and balls. Many times over, people sang Te Deum, a hymn of praise to the glory of the monarch. In a New France far from Versailles, these highly dramatized ceremonies provided inhabitants with a concrete demonstration of royal authority.

Jurisdictions and the other colonies (show)

Equipped with a governmental structure similar to those of the French provinces, New France was distinguished by the immensity of the territory to be administered and the patchy presence of institutions throughout. During the 17th century, Canada was divided into three royal jurisdictions: Québec, Trois-Rivières and Montréal. They were administered by the authorities of Québec, as was also the case for Acadia and Plaisance, the French colony in Newfoundland. On the other hand, the French colonies of the Caribbean had governments equipped with an independent administration that was directly answerable to the Secretary of State for the Navy. By the 18th century, New France encompassed three colonies: Canada, Louisiana and, after Acadia’s cession to the English in 1713, Île Royale. Each of these colonies was equipped with a similar administration, including a Superior Council, a governor, an intendant (or ”commissaire ordonnateur” in Louisiana and in Acadia) and various courts and administrative services. In the secondary cities of their jurisdiction (Montréal, for instance), the intendant or the financial commissary could also rely on a network of permanent or casual sub-delegates to act on his behalf, gather information or address various matters.

The three colonies that made up New France further corresponded to five governments: Québec, Trois-Rivières, Montréal, Louisiana and Acadia. As for the Pays d’en haut, which corresponded to the Great Lakes region, projects to make it a separate governmental domain never came to fruition and its occupants remained under the authority of Québec. In this unorganized territory, the colonial strategy consisted of sending representatives of the crown among the First nations. Generally, these representatives were military officers, though missionaries also relayed news from the state and served as its ambassadors. As the French zone of influence expanded from the Great Lakes to Louisiana, the territory was dotted with trading posts serving as centres for French diplomacy and where officers and small garrisons were located, gifts to the allied nations on behalf of the king. Although they administered very different sets of circumstances, the five governments shared virtually the same organization. Each was led by a gouverneur particulier, a “town” or “regional” governor who answered to the governor general at Québec. Town governors, thus, were the commanding officer responsible for each of the fortified and garrisoned cities of New France: Québec, Trois-Rivières, Montréal, Louisbourg and New Orleans. They were responsible for ensuring compliance with the law and for supervising the security of each town, notably by maintaining its fortifications. In terms of provisioning, the task of the town governors was also to ensure that the troops received adequate rations, munitions and tools. They also saw to their lodging, because in the absence of barracks, the soldiers had to be housed amongst the settlers. Each town governor was seconded by a garrison staff consisting of a lieutenant du roi or king’s lieutenant, a town major and a deputy major. The king’s lieutenant assisted the town governor in his functions and replaced him in his absence, while the town major was responsible for discipline among the garrison troops and managing the lodging of the troops. This structure of government was patterned after the model that had been in place for centuries in the French provinces, each of which had a governor general and staff of its own.

The apparent simplicity of these territorial divisions concealed the ambiguity of the relations between Québec and the regional governments. Although in theory Île Royale and Louisiana were the responsibility of the governor and the intendant of Québec, in practice, they usually received orders directly from France. This situation arose because of the challenges posed to communications by distance and long winters that interrupted contact between Québec and the other Atlantic colonies. A letter from Louisiana could take as much as nine months to reach the St. Lawrence Valley. Still, certain regional governors kept up more consistent correspondence with Québec than others, and managed to coordinate their military actions in wartime. It would be an exaggeration to claim that town governments ignored orders from the capital entirely, but it can certainly be said that their relations varied depending on the military context and the attitude of the specific personalities in office.

Forts and fortifications (show)

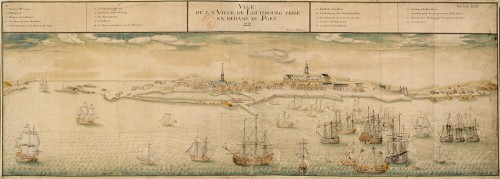

A vast network of defensive works, consisting of backcountry forts, rural redoubts and urban fortifications, supported the exercise of power in New France. This system of defence, which extended over a wide swath of North America, evolved according to the strategic considerations and geopolitical context of the wars that pitted the French against Aboriginal and Anglo-American adversaries. In Québec as in Montréal, for example, the palisades made of wooden stakes erected during the Franco-Iroquois wars of the 17th century were not adequate in the face of an English enemy. They were therefore replaced with masonry enclosures able to resist a siege and support artillery fire. During the Seven Years’ War, other more rudimentary and temporary fortifications were built to protect certain sites. Forts attested to the colony’s changing boundaries and the evolution of its defensive strategy. Fort Chambly, as well as the short-lived Fort Saint-Jean and Sainte-Thérèse, protected the Richelieu valley, considered the main invasion route from the British colonies and the Iroquois territories. Most impressive, perhaps, was the fortress of Louisbourg. Located on Île Royale (now Cape Breton Island) it was at the forefront of France’s efforts to contain the expansion of the British colonies in the 18th century. The fortress sheltered and dominated the town of the same name, the seat of a regional government that had encompassed Île Royale, Île Saint-Jean and other nearby islands. The largest fortress in all of North America, in fact, Louisbourg sheltered a large military base equipped with a permanent garrison. Considered the bulwark of Canada, Louisbourg protected the St. Lawrence estuary to dissuade or resist New England’s attacks, as necessary. Besieged in 1745 then returned to France under treaty, Louisbourg fell into English hands again in 1758, a heavy loss that prefigured the end of New France. It was abandoned at the outcome of the Seven Years’ War.

The government and the people (show)

Compliance with regulations

The king’s “absolute” power was tempered by his duty to ensure the happiness of his subjects. In New France, regulations were aimed at meeting the needs of the settlers and accordingly involved every aspect of life in society. State intervention was particularly visible in the economy. By means of ordinances, the state strove to ensure that all necessary goods and services were available, established currency rates and the price of commodities, and established conditions for practising trades (qualifications, licences, etc.). It also promoted access to land holdings by supervising land development and compliance with the rules of the seigneurial system. Remoteness and slow communications however limited the power of a state which very often did not have the means of suppression required to force settlers to obey the laws. The lack of supervision compelled intendants to frequently repeat their ordinances to ensure compliance. One example has to do with the system of congés, which limited the number of fur trading licences. Despite this system and the very severe penalties imposed on offenders, authorities had great difficulty preventing young people in rural areas from leaving for the forests. In the 18th century, the regulations prohibiting trade with foreigners gave rise to widespread smuggling with New England. Royal power was further weakened because the presence of institutions was not at all consistent from one region to the next. For example, in Acadia, the State machinery was virtually absent. The governor’s authority must have seemed rather remote to the some 1 200 persons scattered along the shoreline in the early 18th century. In this colony, seized from and restored three times to France, the seigneurs held few powers, and the Church, with its network of fledgling parishes, was not able to ensure real supervision.

The Church

The activity of the Catholic Church was inextricable from that of the state because the king’s authority was in theory vested in him by God: to obey the king was to obey God. As in France, the clergy’s responsibility in New France was not limited to spiritual supervision. Through the influence it exercised over behaviour, the Church contributed to the maintenance of order and social cohesion. Myriad instructions issued by bishops and sermons delivered by priests exhorted the peasants to obey the state. In addition to his religious functions, the parish priest played a civil role. He was responsible for keeping the parish registers, which acted as the official records of birth, marriage and death, and would read the royal ordinances at the Sunday Mass before posting them on the church door. Only in the 18th century would the task of reading and displaying ordinances be withdrawn from priests and entrusted to militia captains.

The Militia Captain

In 18th century New France, the captain of the militia was the link between settlers and the authorities. In the 1660s, the limited size of the colony’s military troops forced the authorities to establish a militia. Inspired by France’s coast-guard militia, which defended the coasts from enemy ships, the system obligated all males aged 16 to 60 and able to bear arms to enrol. Organization of the militia covered the entire colony, and each parish usually corresponded to a militia company. Besides the defence of the colony, the militia could be mobilized to pursue criminals and deserters, or to work on roads and fortifications, and to assist in fighting fires in urban centers. Initially, the captain of the militia was a settler appointed by the intendant to take charge of the recruitment and training of militiamen. Over time, though, he acquired a significant role in the administrative operation of the colony. Militia captains were responsible for distributing among the inhabitants the burdencorvéeor statute labour, the billeting of soldiers and the collection of wheat in the event of shortages. Beginning about 1715, militia captains became the principal intermediaries of the state throughout the rural areas. Generally speaking, his fellow citizens held him in esteem. He could generally read and write, and was affluent enough to occupy this unremunerated position. The prestige associated with his duties was his only recompense. He had a reserved pew at church, like the seigneur. He received the host before the other parishioners and was entitled to wear a sword, a privilege usually reserved for nobles. Such marks of social distinction, combined with his roots in the local community, enhanced the authority of the militia officer in a way that enabled him to ensure compliance with regulations and to serve as an intermediary between the government and the people.

The representation of the habitants

New France, like Ancien Régime France itself, was an elitist, unequal society. Those in power were distinguished from the masses by birth, position, wealth and culture. Only the most influential individuals (nobles, seigneurs, major merchants, military officers, magistrates and civil servants) possessed the means to be involved in public affairs. Through the ties of family and clientele that they maintained with the colonial authorities, they could exert a small measure of influence military and commercial policies. Yet regardless of their social origin, the colony’s inhabitants could draw the attention of the authorities to any matter of concern by addressing requests, briefs or petitions directly to the governor and the intendant at Québec. The governor and the intendant would study such claims and formulate an opinion before transmitting it, if they so pleased, to the Secretary of State for the Navy to seek his instructions. The Secretary of State was in no way required to grant the requests submitted to him, although requests from individuals often generated legislation. Within our 21st century system of democratic government, popular representation and legislative power are two concepts that go hand and hand. Such was not the case in New France. Since the right of assembly did not exist under the Ancien Régime, all gatherings had to be authorized in advance by the authorities, who were in no way obligated to rule in favour of such requests. While there would never be any permanent representative institutions in New France, notable men nevertheless had at their disposal, over the decades, a variety of courts before which they expressed their grievances. From 1647 to 1677, the inhabitants of the main towns were represented in turn by procureurs-syndics (trustees), mayors and aldermen. Later, the notables of Québec and Montréal would occasionally meet during administrative assemblies where various issues affecting public welfare would be discussed: the price of bread, weights and measures, etc. Concurrently, the colonial authorities would convene exceptional assemblies to seek the advice of the notables on certain issues. Such consultative mechanisms would disappear in the early 18th century. Until the British Conquest of 1760, merchants periodically initiated assemblies to propose ways of facilitating trade and the movement of goods and people, and to express their broader views on ongoing economic, political and military affairs.

Aldermen and trustees: short-lived municipal officials

Since the Middle Ages, peasant communities throughout France customarily elected representatives to address collective issues and to promote their interests before the authorities. This practice was transplanted across the Atlantic, but its existence in the colonies was short-lived. At the time of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, a number of “procureurs-syndics” (trustees) were elected in Quebec City, Trois-Rivières and Montreal. They were tasked with defending the interests of the residents of each town in the regulation of the fur trade, and to keep them informed of the decisions made by the central authorities at Quebec. More generally, they were expected to monitor the overall operations of the civil administration. The trusteeships were abolished in 1662 and briefly replaced by a mayor and two aldermen the following year, only to be reinstated shortly thereafter by the new Sovereign Council. In 1672, finding this arrangement to be inadequate, Governor Frontenac again endowed Quebec with three aldermen responsible for ensuring the public’s compliance with regulations and for the maintenance of public order. Minister Colbert was displeased by this initiative; however, as he was doing his utmost at this time to reduce the power of municipal authorities across France. The positions of aldermen and trustees alike were thus abolished once and for good in Montreal in 1674, and in Quebec and Trois-Rivières in 1677.

In contrast to the notables of the colony, common folk – the habitants – never possessed a forum where they could freely express their point of view to the authorities. In rural areas, it is nonetheless true, peasants could apply to the intendant for permission to assemble. Under the supervision of the militia captain, they would then discuss matters of general interest, such as the construction of a church or road repairs. The minutes of the assembly were then sent to the intendant or his sub-delegate, who would approve or reject the conclusions. Whether the assemblies were urban or rural, representation was not proportional to the total population of the community. Only a minority succeeded in rising above the masses and had the time and the influence to be active in the public arena.

The absence of representative institutions did not foster collective action. Resistance was mainly expressed in a passive, individual manner. In contrast to the situation in France, riots caused by famine, for instance, seldom occurred in the colony. The rise in the price of basic commodities did provoke reaction among the peasants, but the measures taken by officials to prevent shortages usually made it possible for them to avoid revolts. Elites were even less prone to uprisings, for they were inclined to preserve good relations with the colonial authorities to maintain the favours and recommendations on which their wealth and status depended. Regardless of the reasons for their demands, the colony’s inhabitants continued to be fond of their king and did not question the power of the monarchy, a reflection of a hierarchical view of the social order that was shared by all groups in society at the time.

Further readings (show)

A Bulletin d’histoire politique thematic issue entitled « La gouvernance en Nouvelle-France », vol. 18, no 1 (automne 2009) present several relevant papers:

– Blais, Christian, « La représentation en Nouvelle-France », p. 51-75.

– Chartrand, René, « La gouvernance militaire en Nouvelle-France », p. 125-136.

– Delâge, Denys, « Modèles coloniaux, métaphores familiales et logiques d’empire en Amérique du Nord aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles », p. 103-124.

– Grenier, Benoit, « Pouvoir et contre-pouvoir dans le monde rural laurentien aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles : sonder les limites de l’arbitraire seigneurial », p. 143-163.

– Ouellet, Marie-Eve, « Structures et pratiques dans l’historiographie de l’État en Nouvelle-France », p. 37-49.

Banks, Kenneth J. Chasing Empire across the Sea. Communications and the State in the French Atlantic, 1713-1773. Montréal/Kingston, McGill/Queen’s University Press, 2003. 319 p

Blais, Christian et al. Québec. Quatre siècles d’une capitale. Québec, Publications du Québec, 2008. 692 p.

Coates, Colin M. « La mise en scène du pouvoir : la préséance en Nouvelle-France », Bulletin d’histoire politique, 14, 1 (2005), p. 109-118.

Cloutier, Céline et Paul-Gaston L’Anglais. On a fouillé le passé ! Cinq sites archéologiques de Québec à découvrir. Québec, Ministère de la culture et des communications, 1999. 40 p.

Crowley, Terry. Louisbourg : forteresse et port de l’Atlantique. Ottawa, Société historique du Canada, 1990. Coll. « Brochure historique », no 48.

Havard, Gilles et Cécile Vidal. Histoire de l’Amérique française. Paris, Flammarion, 2008. 863 p.

Mathieu, Jacques. La Nouvelle-France. Les Français en Amérique du Nord XVIe-XVIIIe siècles. Québec, Presses de l’Université Laval, 2001. 271 p.

Richet, Denis. La France moderne : l’esprit des institutions. Paris, Flammarion, 1973. 188 p.

Saint-Hilaire, Marc et al. Les traces de la Nouvelle-France au Québec et en Poitou-Charente. Québec, Presses de l’Université Laval, 2008. 308 p.

Trudel, Marcel. La Nouvelle-France par les textes. Les cadres de vie. Montréal, Hurtubise-HMH, 2003. 432 p.