-

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

- The Explorers

- Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

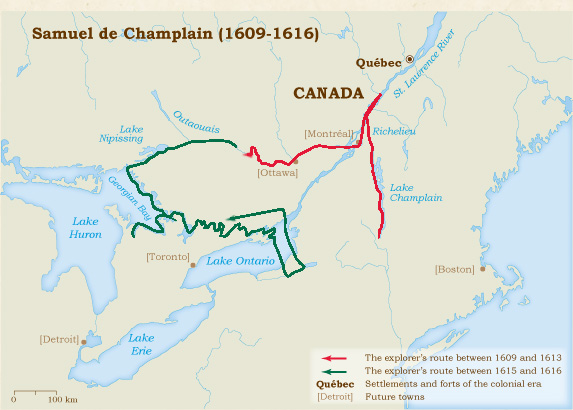

- Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

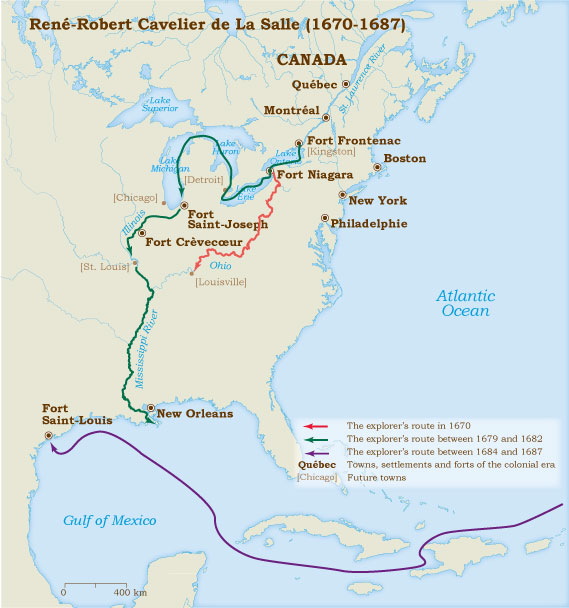

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

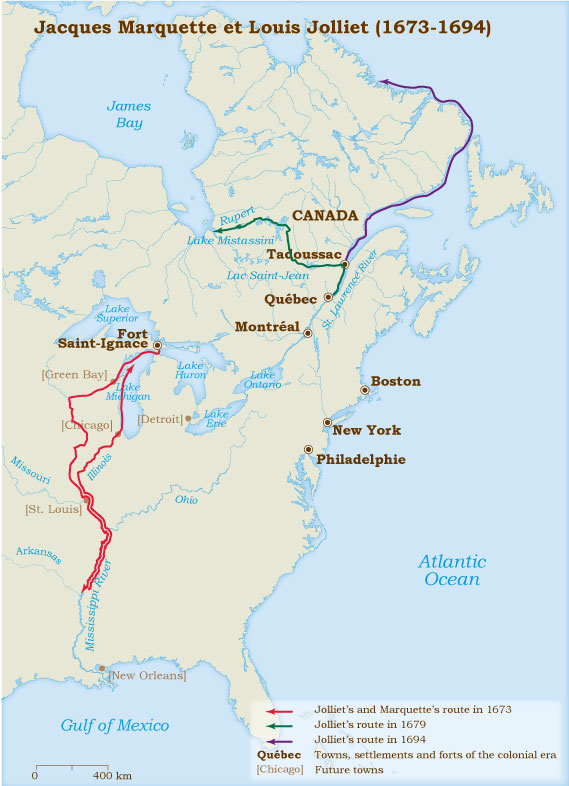

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

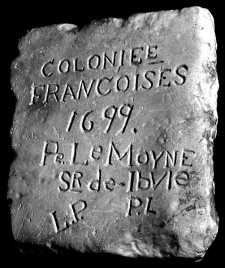

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

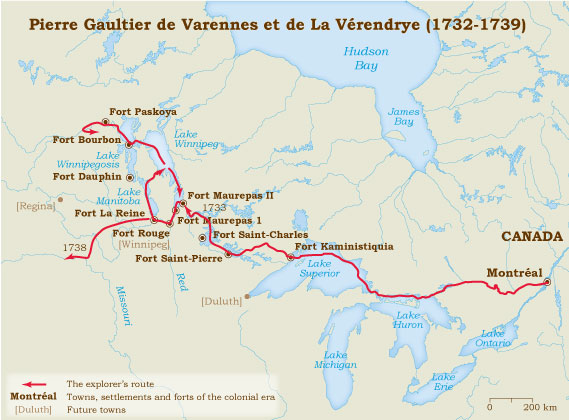

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Economic Activities

- Population

- Daily Life

- Heritage

- Useful links

- Credits

Colonies and Empires

French Colonial Expansion and Franco-Amerindian Alliances

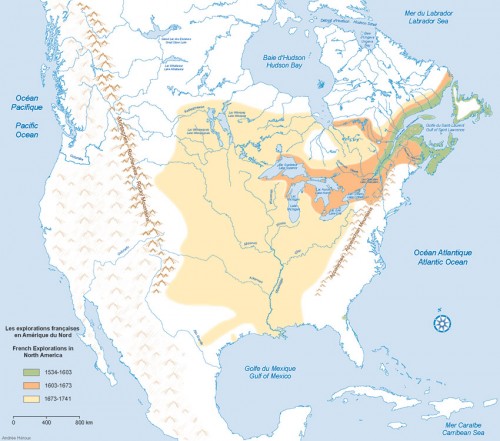

Over the course of the 240 years that separated Giovanni da Verrazano’s voyage of exploration in 1524 and the dismantling of New France in 1763, the French left their mark on the North American territory in a variety of ways. Through their manner of clearing and dividing the land, establishing villages and cities, building a network of roads and trails, and developing the territory with varied types of construction, they transformed and adapted environments according to their needs.

Setting out from a few small colonized areas mainly found along the St. Lawrence River in the 17th century, the French journeyed through a large part of North America. On the eve of the British conquest, New France extended from Hudson Bay in the north to the mouth of the Mississippi in the south, and from Acadia in the east to the foothills of the Rockies in the west.

Pushing ever further west and south to find a constant supply of fur, the French deployed a whole network of alliances with the most influential Aboriginal tribes, economic and military alliances that enabled them not only to contain the English on the Atlantic seaboard for over 150 years, but also to ensure the survival of an under-populated New France whose borders would have been difficult to defend otherwise.

Introduction (show)

After the Spanish discovery of America in 1492, the other major European powers did not want to be outdone. In June 1497, theexplorer John Cabot, sailing for the English crown, reached Newfoundland, while the following year, Joao Fernandes explored the north-east of the continent for Portugal. In the early 16th century, Breton and Norman fishermen came seeking cod on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, but it was not until 1523 that the first French expedition took place. By order of François I, Giovanni da Verrazano of Florence left Dieppe to discover a new route to China. The following year, aboard the Dauphine, he surveyed the coasts of North America, sailed along the shores of the Carolinas and Virginia, then made his way up toward Cape Breton Island.

Ten years later, François I called on the mariner of Saint-Malo, Jacques Cartier, and commissioned him to go beyond the “new lands.” On his first voyage in 1534, Cartier got as far as the Gulf of St. Lawrence and made contact with the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, who spoke of a “kingdom of the Saguenay” with fabulous riches. On his second expedition the following year, he made his way up the river as far as Hochelaga, an Aboriginal village erected on the site of the future city of Montréal.

On his return to France, Cartier persuaded François I of the benefits the Crown could hope to derive from colonizing this territory, which was called “New France.” In 1541, Cartier seconded Jean-François de La Roque de Roberval, commissioned to found a colony on the north shore of the St. Lawrence, to continue seeking a passage to Asia and to bring back precious metals. Cartier left Saint-Malo in 1541, but Roberval, who was unable to raise all of the required funds, set sail only the following spring. Having sustained a number of human losses and faced with the threat of conflict with the Iroquoians of Stadacona (Québec), Cartier and his crew abandoned Cap-Rouge in the spring of 1542. At In Newfoundland, they met Roberval who ordered them to return with him to Cap-Rouge; they refused and then fled during the night. Roberval nevertheless continued his journey to Cap-Rouge, which he had to abandon in the spring of 1543 because of worsening conflicts with the Iroquoians.

The civil war between Catholics and Protestants in France curtailed overseas ambitions. After the failure of the Huguenots in Brazil in 1555, and the establishment of the French settlement at Fort Caroline in 1564–1565, it was not until the early 17th century that the French royal court decided to send ships to the North American continent again. The signing of the Edict of Nantes in April 1598, which ended the wars of religion, allowed King Henri IV to turn his attention once again to America. Pierre Du Gua de Monts, who secured a trade monopoly in 1603 and in 1609, launched several expeditions to Canada. In 1603, François Gravé Du Pont led a trade campaign and travelled as far as Hochelaga (now Montréal), following the same route as Cartier. The following year, Du Gua de Monts led an expedition and explored the coasts of Acadia and New England to find a suitable site for establishing a colony. After a failed attempt at settlement on Île Sainte-Croix, the entire crew moved to Port-Royal, which would also be abandoned in 1607.

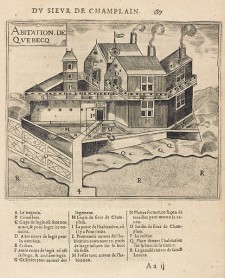

Samuel de Champlain, a captain of the royal navy who took part in the first voyages to the Americas as a navigator, explorer and cartographer, left again for the New World in April 1608. Appointed to serve as the lieutenant of Du Gua de Monts, he sailed up the St. Lawrence in the company of François Gravé Du Pont and his crew, and built an “abitation” on the rocky plateau that overlooked the river. Following the teachings of his mentor Gravé Du Pont, Champlain called it Québec, which in the Montagnais language means “the place where the river narrows.” The capital of New France was born.

The Exploration of the Continent (show)

As soon as the city of Québec was founded, Champlain set out to discover the interior of the continent. In 1609, he explored Iroquois country and went as far as the lake that he named after himself. Four years later, he began exploring the “Pays d’en haut,” or the upper country, which refers to the Great Lakes region. In the course of his various voyages, he made his way up the Ottawa River in 1613 and reached Lake Huron, which he would later call the “freshwater sea.” After Champlain, many other explorers led more or less official expeditions. Thus, around 1621–1623, Étienne Brûlé reached Lake Superior while looking for copper mines. In 1626, a Recollet missionary, Father Joseph de la Roche Daillon, journeyed among the Neutral tribe, which lived near the shores of Lake Erie.

The Search for a Passage to the “Western sea”

Until the end of the 18th century, one of France’s objectives was to reach the Pacific Ocean, also called the “Western sea” and the “sea of China.” The French wanted access to the riches of the Orient without having to sail around Cape Horn. As early as 1524, Verrazano was commissioned by François I to discover the passage to the Orient. Cartier and Champlain had also thought they had discovered this passage on exploring the St. Lawrence. Beginning in the 1630s, the principal agents of discovery and exploration of the continent were Jesuit missionaries, who also hoped to evangelize the Aboriginal peoples. In 1634, Father Jean Nicollet travelled as far as Lake Michigan and reached the Baie des Puants (today Green Bay in Wisconsin). After exploring the surrounding region, he stopped seeking a passage to the “Western sea” and returned to Québec. In July 1647, Father Jean de Quen made his way up the Saguenay as far as Lac Saint-Jean and, in 1661, Fathers Claude Dablon and Gabriel Druillettes took the same route with Montagnais guides and explored the region, also hoping to find the much sought-after passage. After travelling through Iroquois country, to try to establish a mission, the Jesuits concentrated on the Great Lakes region. With a view to founding a mission there, Father Claude Allouez explored the shores of Lake Superior from Sault-Sainte-Marie to Lake Nipigon between 1665 and 1667. Two years later, he made his way to the Baie des Puants (the bay of stinking waters) and explored the area as far as the Fox River.

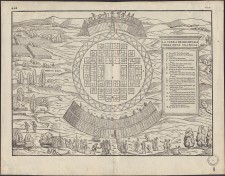

Map of the New Discoveries North of the South Sea from Eastern Siberia and the Kamtchatka and West of the New France

At the same time, in the 1660s, a vast westward movement of people set out from Montréal. The scattering of the Hurons, allies and intermediaries of the French, pushed merchants from this city to venture out and secure supplies of furs from the Aboriginal peoples of the Great Lakes region, now the area that had the most abundant fur-bearing animal resources. Many “coureurs de bois” set out en route to the “Pays d’en haut” and established trading posts there.

The colonial authorities also decided to support new exploratory voyages in the interior of the continent, despite the misgivings of Louis XIV and Jean-Baptiste Colbert, councillor of state and intendant of finances and the navy. In 1665, the Intendant of Canada, Jean Talon, received instructions to organize expeditions that once again aimed to discover a navigable route to the “Western sea.” In 1670, he sent Simon-François Daumont de Saint-Lusson to explore the Lake Superior area. On June 14, 1671, he was in Sault-Sainte-Marie. In front of an assembly of fourteen Amerindian nations, he officially took possession of the area “of the said place […] and also lakes Huron and Superior, […] and all the other contiguous and adjacent countries, rivers, lakes and streams, here, both discovered and yet to be discovered, which are bordered on one side by the Northern and Western seas, and on the other, by the Southern sea….”

In 1672, Talon put a merchant of Québec, Louis Jolliet, in charge of surveying the “great river” that Aboriginal peoples “call the Michissipi believed to flow into the sea of California.” In December, Jolliet reached the mission of Saint-Ignace, located on the north shore of the Strait of Michilimackinac. He was greeted there by Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit with whom he continued his voyage. Together, the two men reached Wisconsin and then discovered the Mississippi, which they called the “Colbert River.” By canoe, they went as far as the river’s confluence with the Arkansas River where they realized that the river flowed to the south. They concluded that it probably flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, and not the sea of China, as they had hoped. They then backtracked and returned to the Saint-Ignace mission.

Louisiana

In 1673, a native of Rouen sponsored by Governor Frontenac, René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle, built Fort Frontenac on the eastern end of Lake Ontario. This post would serve as a point of departure for several expeditions aiming to explore the shores of the Mississippi.

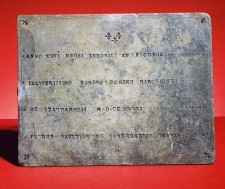

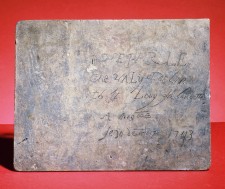

After several fruitless attempts, Cavelier de La Salle reached the river’s delta in 1682. On April 9, he had a cross erected and a column adorned with the arms of France, and he took solemn possession of the country he named Louisiana in honour of Louis XIV. On returning to France, Cavelier de La Salle was given a new commission to find the mouth of the Mississippi by sea. He ran aground on the coast of the current State of Texas, where he was murdered by one of his companions in 1687.

“I have taken and do now take possession […] of this country of Louisiana, the seas, harbours, ports, bays, adjacent straits; and all the nations, people, provinces, cities, towns, villages, mines, minerals, […], fisheries, streams and rivers comprised in the extent of Louisiana, […] and this with the consent of the […] Motantees, Illinois, Mesigameas (Metchigamias), Akansas, Natches, and Koroas, which are the most considerable nations dwelling therein, with whom also we have made alliance.”

Archives nationales de Paris, Colonies, C13C 3, f.° 28v. Jacques Métairie, April 9,1682, “Procès-Verbal de la prise de possession de Louisiane.” (Memoir of taking possession of the country of Louisiana)

During the decade of the 1690s, France became aware of the importance of Cavelier de La Salle’s discovery. They realized that the British – with whom they were in virtually permanent conflict – could endanger the Canadian colony by attacking through the Mississippi. Louisiana then appeared to be a zone that could serve as a barrier against English territorial and commercial expansion. In February 1699, an expedition led by the Canadian Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville (1661–1706) reached a place that was given the name Biloxi, referring to the First Nation who lived nearby (today, in Mississippi). The French then launched many explorations with a variety of objectives: to establish alliances with the Aboriginal nations to ensure the security of the emerging colony; to seek natural resources; and to conduct trade relations with the Spanish colonies of New Mexico. The search for a passage to the “Western Sea” continued to be a goal.

In 1700, Pierre Le Sueur left Biloxi with a dozen men and made his way up the Mississippi as far as the Saint-Pierre River. In 1714, Louis Juchereau de Saint-Denis followed the Red River as far as Natchitoches country where he founded a post. He continued on, crossing Texas, until he reached San Juan Bautista (today, Piedras Negras, Mexico). However, this route was not much used, despite the desire of Louisiana authorities to establish trade relations with the Spanish of New Spain. Five years later, Jean-Baptiste Bénard de La Harpe reached the Arkansas River, and in 1723–1724, Étienne Veniard de Bourgmont explored the Missouri and surveyed the mouth of the Platte River. In 1739, two Canadian traders and brothers, Pierre-Antoine and Paul Mallet, set out from Fort de Chartres, located in Illinois country, and travelled as far as Santa Fe via the Great Plains.

Finally, a family of explorers, the La Vérendrye family, continued to look for the Western sea. In 1728, Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye was appointed commander of Fort Kaministiquia, at the head of Lake Superior, established in 1717 by Zacharie Robutel de La Noue.

From 1731, the fort was used as a rear base for exploring the region around lakes Winnipeg and Manitoba as well as the upper Missouri. La Vérendrye’s sons, Louis-Joseph and François, would push exploration as far as Big Horn, today in the State of Wyoming.

On the Importance of Discovering a Passage to the Western sea:

“If the Western sea is discovered, France and the Colony could derive great benefits in trade, because Lake Superior flows into Lake Huron, which flows into Lake Erie, which in turn flows into Lake Ontario, whose waters form the St. Lawrence River; in each of these lakes, which are navigable, we could have barques to transport merchandise that from the Western sea to Lake Superior could be transported in canoes, since the rivers are very navigable.

The navigation would be brief, compared with European vessels and subject to far fewer risks and costs, which would provide such great benefit over the trade of that country that no European nation could compete with us.”

Decreed by the Council of the Marine, February 3, 1717.

–L.A. de Bourbon, Maréchal d’Estrées (cited in Pierre Margry, Découvertes et établissements des Français dans l’ouest et dans le sud de l’Amérique septentrionale, 1614–1754, Paris: Maisonneuve, 1879–1888, vol. 6, pp. 501–503).

Colonization (show)

The same model of colonization applied to Canada and Louisiana. After having financed the first expeditions, France neglected the newly discovered territories and abandoned them to individuals or private companies before renewing its interest, either willingly or because it was compelled to do so. There were two reasons for the lack of interest. First, hopes of quick riches, as the Spanish had enjoyed in South America, were soon dashed. No gold mines were discovered in Canada or in Louisiana. Second, France feared the depopulation of its kingdom and thereby the weakening of its power in Europe. In 1666, Colbert expressed this fear to Intendant Talon: “It would not be prudent to depopulate his Kingdom as he would have to do to populate Canada.” Thus few colonists were sent to settle in the new territories.

Monarchical power was satisfied with encouraging trade companies that tried their luck overseas. This was the case in Canada, where colonization began in the early 17th century through the fish and fur trade. New France’s trading company, the Company of One Hundred Associates, founded in 1627 and managed by noblemen and entrepreneurs, was granted a monopoly to exploit and administer the colony. It was under its control that colonization actually got underway, particularly in three centres, Québec, Trois-Rivières and Montréal, founded respectively in 1608, 1634 and 1642.

It was not until Colbert took power that the French Royal Court at Versailles decided to get more involved in the development of Canada. In 1663, an institutional regime was established that made Canada a French province like the others, but that depended on the Secretary of State for the Navy and the Colonies, Jean-Baptiste Colbert. This was the era of the colony’s most significant growth. From 1663 to 1673, nearly 800 young women—“les Filles du Roi” (the King’s daughters)—were sent to the colony to marry the many available bachelors. In 1665, the Secretary of State for the Navy sent the Carignan-Salières regiment to pacify the Iroquois nations. Among the thousand soldiers deployed there, over four hundred decided to become inhabitants following the signing of the peace in 1667.

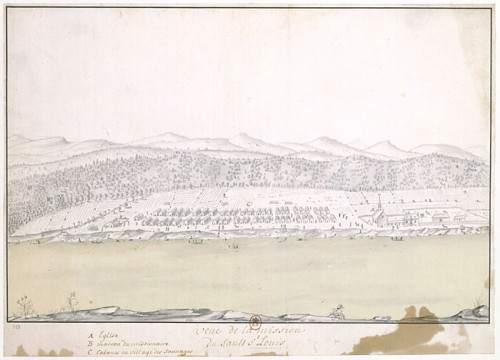

Having long been neglected because of the War of the Spanish succession (1701–1713), Louisiana was ceded in 1712 to a company managed by a wealthy merchant named Antoine Crozat. In 1717, it was returned to the Company of the Indies, founded by the Scottish banker, John Law. The banker succeeded in sending over 5,000 people to the colony but his company sustained a spectacular bankruptcy in 1720. The French Crown was forced to liquidate the debts, restructure the company and then retake the entire colony in 1731, following the massacre of colonists at the Natchez post. The new arrivals in Louisiana settled in Mobile, founded in 1701 by Le Moyne d’Iberville, then in New Orleans, established in 1718 by his brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville.

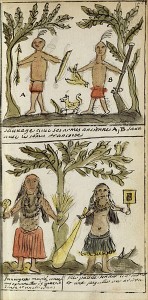

The Missions

In 1615, three Recollet priests, Fathers Denis Jamet, Jean Dolbeau and Joseph Le Caron, arrived in New France. Dolbeau was ordered to convert the Montagnais of the lower St. Lawrence while Le Caron was sent to Huronia, a territory located in what is now southwestern Ontario. He stayed there for one winter and then returned to Québec. Experiencing many difficulties, the Recollets would not return among the Hurons until 1623. That year, Fathers Le Caron and Nicolas Viel as well as Brother Gabriel Sagard established a mission in the village of Quienonascaran. The following year, Father Viel found himself alone in converting the Hurons. The Hurons were not, however, so easily convinced. Only a few newborn infants and dying elders were baptized. In 1625 unsatisfactory results led the Recollets to call in the Jesuits, renowned for their evangelizing missions, particularly in Asia.

Shortly after the first Jesuit missionaries—Fathers Énemond Massé, Charles Lalemant and Jean de Brébeuf—arrived, the Jesuits succeeded in supplanting the Recollets. By 1632, they alone were responsible for the pastoral and missionary work of the Roman Catholic Church in Canada. The same year saw the publication of the first volume of their Jesuit Relations, an exchange of letters between the missionaries and their home base in Paris.

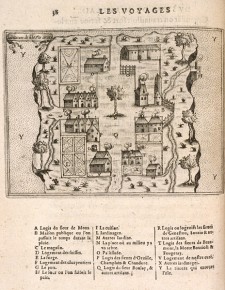

Starting in 1634, they established four missions in the main Huron villages, and five years later, on the Wye River, near Midland Bay, the main mission of Saint-Marie. The mission was surrounded by a palisade that protected the living quarters, a chapel, a hospital, a forge, a mill and a rest area for missionaries returning from Native villages. In 1647, 18 priests assisted by 24 laymen were serving missions in Huron territory. They took their evangelizing work to the neighbouring Petuns, the Neutrals, the Saulteux and the Ottawas. The results were disappointing: only a few hundred men and infants were converted to Christianity. During the conflict between the Hurons and the Iroquois, eight priests were martyred by the Iroquois. This war ended with the scattering of the Hurons in 1649 and the abandonment of the Jesuit missions in this territory.

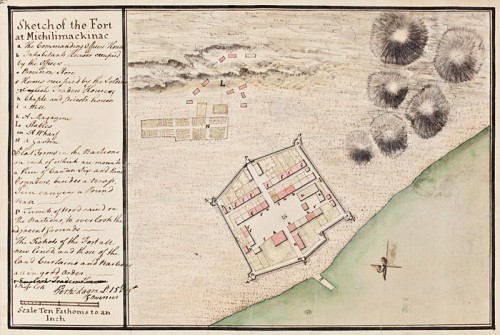

With western expansion, the Jesuits hoped to achieve something by settling in the Great Lakes region. In 1665, Father Claude Allouez reached Chequamegon Bay on the shores of Lake Superior, where he founded La Pointe mission. For 30 years, the Jesuits established new missions, in particular at Baie des Puants, Sault-Sainte-Marie and Kaskaskia. In 1671, Marquette moved the La Pointe mission to Saint-Ignace (or Michilimackinac). It would later be used for all westward missions. According to the baron de Lahontan, “it is like their headquarters in this country, & all the missions spread among the other savage nations depend on this residence.”

The first missions in Louisiana were founded by Fathers François de Montigny and Albert Davion, two priests from the Seminary of Québec who settled among the Yasous and the Natchez. Others were later established among the Arkansas, the Choctaws and the Alibamons, but the Natchez uprising of 1729 led to the destruction of most of them.

The Jesuits had a small House [in Michilimackinac] beside a kind of Church inside a palisade that separated them from the Huron Village. These good Fathers employ their Theology & their patience in vain to convert the unbelieving ignorant. It is true that they often baptize dying infants, & a few old people, who agree to receive Baptism when they are at death’s door.

Lahontan (Louis Armand de Lom D’Arce, baron de), Nouveau voyage de M. le baron de Lahontan dans l’Amérique septentrionale, La Haye, 1703, p. 115.

The Founding of Western Posts

The colonial centres of Québec, Montréal, Mobile and New Orleans served as starting points new exploration. As the explorers penetrated the interior of the continent, they marked out their paths with small forts that served as trading posts or shelters as needed. They could become permanent posts, but many were abandoned as soon as the expedition concluded.

This was also the case for trading posts. Based on the bartering system, the fur trade emerged with the first voyages of the 16th century. French and Native people became accustomed to trading manufactured goods for pelts that were sent to the mother country to supply the hat industry. Fur gradually became the primary resource of New France, despite the efforts of Colbert and Talon to diversify the economy. In the 17th century, Native people were still bringing their furs to the colony’s principal centres,- in particular the great market held at Montréal every year; but merchants were gradually forced to travel further afield to obtain the precious merchandise and ensure it would not be sold to British competitors. As a result, a number of trading posts were built in the Great Lakes region. Some were simply houses built in Native villages, others were used both as a point of sale and a warehouse for trade goods. The stored merchandise was later redistributed to all the smaller posts in the region. Michilimackinac, located at the mouth of Lake Michigan, Fort de Chartres and Niagara are examples.

The French authorities did not take a favourable view of the establishment of new permanent settlements in the Pays d’en haut. The French royal court felt that these posts weakened the growing colony of Canada. Colbert thought it necessary to concentrate the settlements around Québec, Trois-Rivières and Montréal to provide better security, in particular with regard to the Iroquois nations. Yet in the colony, the authorities allowed certain young Canadians to set out for the Great Lakes region to conduct the fur trade. Some were given a permit authorizing them to do so. Most were not, and became known as the “coureurs de bois” (literally, “runners of the woods”). On the routes leading to the Pays d’en haut or on arriving there, they built forts. Thus, Cavelier de La Salle, who dominated trade in the region south of the Great Lakes even as he conducted explorations, established forts in Niagara in 1676, in Saint-Joseph des Illinois in 1679, and on the Illinois and Mississippi rivers in 1680 (Fort Crèvecœur and Fort Prud’homme). Some were later abandoned, others occupied by the soldiers of the Troupes de la Marine, who were responsible both for protecting the interests of the traders and for keeping them under surveillance.

“It would be better to limit ourselves to a territory that the Colony will be in a position to maintain, than to embrace too vast an area a part of which we might one day be forced to abandon with some diminishment of the reputation of his Ma[jes]ty, & and this Crown.”

Letter from Colbert to Talon, Versailles, January 5, 1666.

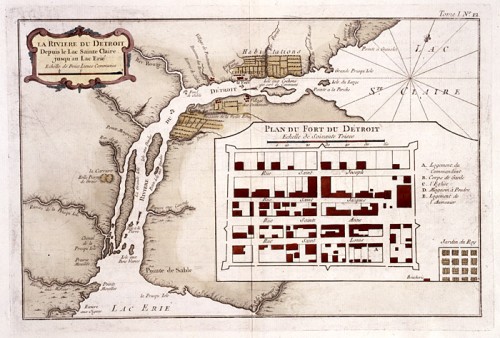

In 1696, a serious economic crisis hit the fur sector. The price of pelts collapsed because of surplus production. The French royal court then decided to close all the western posts. Five years later it reversed its decision, no doubt because of d’Iberville’s colonization attempts and the fact that France had taken possession of Louisiana. The geostrategic importance of the Mississippi Valley led Minister of Marine, Louis Phélypeaux, comte de Pontchartrain to implement a policy that historians called defensive imperialism. It consisted of creating small coloniesat strategic crossing points. The first was Detroit, founded in 1701 by Antoine de Lamothe-Cadillac. He wanted to establish a true “agricultural colony,” attract as many people as possible and acquire wealth as quickly as he could. This was how a chain of forts from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico was gradually established.

In 1709, Fort Saint-Louis was built at Mobile, in Louisiana, at the entry to the Alabama River. Another, fort was built in 1716, among the Natchez, and the following year, Fort Toulouse was constructed at the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers. Fort de Chartres was established in 1720 and Fort Arkansas, the following year. Not all of these forts were the same size. Some were protected by a simple palisade of logs whereas others, were built of stone, and equipped with cannons. Garrisons sometimes consisted of a handful of men, and sometimes one or several companies of soldiers.

Military Colonization

Some forts expanded because of the importance they acquired in the region, others as the result of a colonization policy that aimed to encourage soldiers to remain in the country and take land. This policy had been implemented in the 1660s with the granting of bonuses to the men of the Carignan-Salières regiment who wished to remain in America. At the request of Governor Jacques-René de Brisay, Marquis de Denonville, the policy was resumed in another form in 1686. Every year, two soldiers per company were authorized to leave service on condition that they commit to developing the land granted to them. In the same year, 1686, 20 demobilized soldiers nevertheless became inhabitants at Montréal. In 1701, Lamothe-Cadillac wished to populate “his” colony of Detroit in the same way. Eight years later, the post had 174 inhabitants.

Throughout the 18th century, various measures encouraged soldiers to settle at the site of their garrison. In the Pays d’en haut, where the garrison soldiers at a post were usually replaced every three years, soldiers were allowed to remain longer to become accustomed to the location. In 1717, the French royal court asked the Governor of Louisiana, Le Moyne de Bienville, to recommend “to the officers to ensure that the soldiers work (…) at making gardens for each of their barrack-rooms and even allow soldiers who are hard-working to start building small living quarters on their own.” It was hoped that in this way, soldiers would be encouraged to stay on permanently in the colony. In addition, these future colonists would be entitled to a settlement bonus that included supplies, clothing and full pay for three years. In September 1734, an edict established the conditions for soldiers to obtain leave: except for those settling in Louisiana to farm, soldiers were required to practise a useful trade, as masons, carpenters, cabinetmakers, barrelmakers, roofers, toolmakers, locksmiths or gunsmiths. Later, soldiers were also encouraged to marry so that they would be less tempted to become coureurs de bois. In 1750, these measures were supplemented with the shipment of additional troops to replace departing soldier-colonists.

According to the U.S. historian Carl Brasseaux, 1,500 soldiers settled in Louisiana after leaving service between 1731 and 1762. In Canadian historian Allan Greer’s view, the soldiers were the largest source of colonists in Canada. In fact, military colonization allowed 30 soldiers per year to settle in this colony from 1713 to 1756, or 1,300 over 43 years. Some posts in the interior of the continent expanded because of this influx of colonists. This was true in particular of Detroit and the Illinois region, which was attached to Louisiana starting in 1718. Many soldiers acquired plots of land near Fort de Chartres on leaving service. Some cultivated the land or raised livestock whereas others took up the fur trade. However, most opted for the colonial centres of Montréal, Québec and New Orleans. As a result, the forts remained primarily warehouses and trading posts and only seldom became permanent settlements. That is why historians frequently talk about “colonisation sans peuplement,” or “colonization without settlement” in connection with French policy.

Trade in the Colonies

Throughout the entire French regime, the fur trade was the principal driver of the Canadian economy. From 1720 to 1740, 200,000 to 400,000 pelts were exported every year to France from Montréal or Québec. Their value represented nearly 70% of exports. In Louisiana, exports were less significant—about 50,000 pelts, 100,000 during the best years—but the fur trade nevertheless played an important role in the economy of the colony.

Merchant trading with an Indian, detail from frontispiece: A map of the Inhabited Part of Canada…, William Fadden, 1777

The regulation of trade evolved over the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1654, Governor Jean de Lauson established “permits,” which, by 1681 were limited to 25 per year. The system was abolished by the edict of May 21, 1696 and reinstated 20 years later through the declaration of April 28, 1716 to assist noble families in need. Following a suspension from 1723 to 1728, permits were later sold directly to merchants and occasionally to military officers. In fact, fur commerce was in the hands of a few merchants in Montréal. These merchants supplied trade goods to “merchant-outfitters” who organized expeditions to the Pays d’en haut.

In Louisiana, companies held an exclusive monopoly on the fur trade in exchange for an annual royalty to the king. They had to maintain a clerk in every fort who was responsible for merchandise. In 1731, when the Crown reasserted control over the colony, it ordered that trade with the Native communities should be open to everyone. During the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748), the Governor implemented a new policy whereby the commander of each fort had to supervise stocks and oversee the granting of trade permits.

As in the Pays d’en haut, trade was rapidly dominated by a small group of families belonging to the colony’s elite. Officers stationed in forts in the hinterland and the merchants of Montréal and New Orleans formed partnerships, which sometimes coincided with matrimonial alliances.

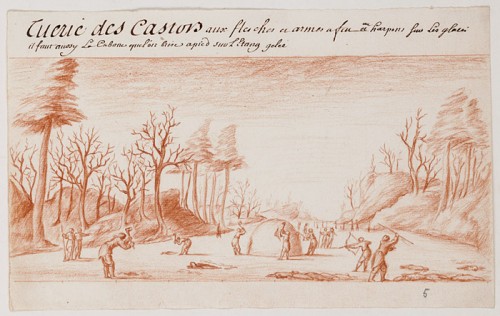

In Canada, the most widely hunted animal was beaver. Traders bought prepared beaver pelts. There were two types of furs: the sun-dried beaver pelt, of little value, and castor gras, a pelt worn by the hunter for two or three years, which gained a sheen from his sweat. Of superior quality, castor gras was the most expensive and the most sought after. The French also bought otter, martin and fox pelts. In Louisiana, local grey beaver was clearly less in demand than the brown beaver of the Pays d’en haut. The French preferred bear, bison and above all, white-tailed deer, the most hunted animal in the Mississippi Valley.

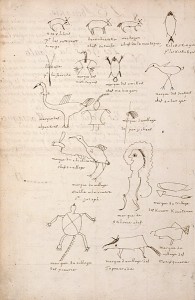

In exchange for furs, Native trappers accepted all kinds of goods, including utilitarian objects (copper or iron cauldrons, knives, axes, pickaxes, thimbles, needles, pins, etc.); arms (guns and gunpowder, musket balls and gunflints); and clothing and personal items (shirts, hats, sheets, blankets, knick-knacks, vermilion, bells, porcelain beads). Guns were particularly valued.

As colonization advanced in Louisiana, indigo and tobacco growing occupied an increasingly important place in the colony’s economy. The French court encouraged these two crops, because it saw a way of saving money on imports to the mother country. Indeed, every year, France spent over six million pounds to buy tobacco from England. As a result, Versailles placed a great deal of hope in Louisiana and its plantations, particularly those of the Natchez whose land was considered most suitable for tobacco growing. Indigo crops, which produced a highly prized blue dye in France, continued to be the most lucrative undertaking.

Franco-Amerindian Alliances (show)

Exploring North America and settling in a few strategic locations would have been impossible without alliances with the Aboriginal nations. In 1603, Champlain was able to sail up the St. Lawrence because Gravé Du Pont, in charge of the expedition, concluded an initial alliance with the Montagnais Chief Anadabijou at Pointe Saint-Mathieu (today, Baie-Sainte-Catherine). From this moment on, the French would make several oral or written commitments to Aboriginal First Nations.

They soon understood that cordial relations would be essential if they wanted to establish permanent settlements in North America. A small population and limited troops compelled them to do so. Such alliances were also fundamental for successfully exploring the continent. Without agreement from a First Nation, an explorer could not travel through their territory nor make further discoveries. Alliances were also required for trade. The alliances that Champlain concluded with the Montagnais, the Algonquins and the Etchemins gave him access to a vast trading network stretching from the St. Lawrence Valley to the Pays d’en haut.

Above all, trade depended on good relations with Aboriginal partners. For Aboriginal people, trade could take place only through alliances. At trade meetings, gifts were discussed, not prices. This was quite different from the situation in Europe, where reciprocity prevailed over a market economy. For Native people, exchanging merchandise had a symbolic value: it represented political reciprocity between independent groups whereas an absence of trade amounted to war.

The Metaphor of the Father

In the Native American tradition, trading goods involves the creation of fictional kinship relationships among participants. For trade to occur, the “Other” – the newcomer or outsider – must join their society. That is why Aboriginal peoples welcomed the Other as a relative. In the first half of the 17th century, the Hurons called the French “brothers,” as the term brother implied a degree of equality between partners. But the defeat of the Huron by the Five Nations Iroquois in 1649 turned the tide. The Governor of Canada became the “father” of the Hurons, who placed themselves (or at least were considered to have placed themselves) under his protection. In the 18th century, “father” was what First Nations called the Governor of Canada and his representatives . The alliance uniting the French and the Aboriginal peoples was symbolized as a large family in which Native people were now the metaphorical children of the French father.

Complicating the situation is the fact that Aboriginal people and the French did not interpret this metaphorical “fatherhood” in the same way. In Native societies, a father had no compelling power and was obliged to be generous to his children, to support them without regard to cost. In the Ancien Régime of France, a father could be an absolute authority figure. Thus it was generally said that the king was the father of the French people.

“The savage does not know what it is to obey: it is more necessary to entreat him than to command him (…). The father does not venture to exercise authority over his son, nor does the chief dare give commands to his soldier; he will entreat him gently, and if anyone is stubborn in regard to the proposed movement, it is necessary to flatter him in order to dissuade him, otherwise, he will go further in his opposition.”

Nicolas Perrot (v.1644–1717), Mémoire sur les mœurs, coustumes et relligion des sauvages de l’Amérique septentrionale, Leipzig and Paris: Franck, Herodd, 1864.

Despite a number of vain attempts on the part of French governors and officers to impose this European concept of fatherhood, the Franco-Amerindian alliance was actually based on the Native understanding of the term. The colonial authorities,, had no compelling powers over their “Aboriginal children” . In order to maintain their alliances, and the status of “father,” the French the responsibility of providing gifts to “their children.” The distribution of gifts was methodically organized. Every year, Native chiefs gathered at Montréal or at Mobile to receive a variety of goods from the governor in person. The distribution of gifts was accompanied by feasts provided by the colonial authorities to renew vows of friendship.

Military Alliances

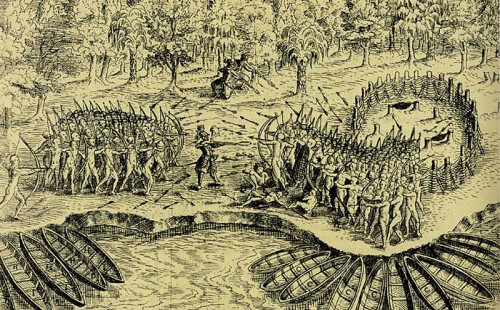

Among Amerindians, a trading alliance inevitably led to a military alliance. As a result, the allied nations demanded as a condition for trade that the French provide them with protection or take part in their wars. This explains the French involvement in the war between the Hurons and the Iroquois in the early 17th century. Champlain was forced to fight alongside the Hurons, the first economic allies of the French, and witnessed their victory at Lake Champlain in 1609. French participation in that battle was the reason for long-standing hostility on the part of the Iroquois.

Alliances among the First Nations were not inviolable, eternal contracts. They had to be endlessly consolidated or renewed, and it was not only trade or French military strength that made them prosper, but myriad diplomatic relations. Diplomacy was based on Native rituals that the French adopted. Thus, during peace negotiations, the first step in the diplomatic process often consisted of an invitation extended by either of the parties. It identified the time and place of the meeting. The first contact between ambassadors and their hosts usually took place on the edge of a forest, near an appropriate Native village. After greeting one another, mourning the dead and exchanging wampum (a pearl or shell necklace) or gifts to express sympathy, the participants would hold the traditional peace pipe ceremony. This ceremony concluded with a great feast where the nations would dance and sing to convey their good intentions toward each other.

In the mid-17th century, following their defeat by the Iroquois and their dispersal throughout the Great Lakes region, the Hurons allied themselves with the “confederation of the three fires,” comprising the Saulteux, the Potatwatomi and the Ottawas. These nations, who lived in the Pays d’en haut, became in turn the allies of the French. Later, several other nations joined the ranks of the allies, in particular, the Illinois, the Miami and the Sioux, although they conceded the main role to the four founding nations of the “confederation.” This Franco-Aboriginal league was united by two main ties, in addition to trade: a common enemy, the Iroquois, and the fear of British expansion. In Louisiana, the ties uniting France with its Native allies were the same as those in the Pays d’en haut, but the common enemy was the Chickasaw. Armed by the British, this people threatened the Choctaw nation who became the main ally of the French.

The Iroquois represented a real threat to Canada. In the 17th century, they were able to gather nearly 3,000 warriors armed by the English, far more men than the colony could muster. In the 1660s, the French government sent the Carignan-Salières regiment for protection. .Two expeditions attacked Iroquois villages in 1665 and 1666 and forced them to make peace the following year, but they attacked New France again in the early 1680s. They wanted to protect their hunting territory from French expansion. The new governor of Canada, Joseph-Antoine le Febvre de La Barre, persuaded the French court to send him a contingent of 500 Troupes de la Marine to invade the Iroquois territories and destroy them once and for all. The 1684 expedition proved a disaster, just like the one led three years later by La Barre’s successor, the Marquis de Denonville, with twice as many soldiers. The situation became more critical because the Iroquois were now threatening the very heart of the colony. In 1689, 1,500 Iroquois warriors succeeded in attacking and destroying the small town of Lachine, located near Montréal. It was then apparent that despite reinforcements, the colony could not survive without the military support of its Aboriginal allies. The Iroquois would continue to be a threat until 1701, with the signing of the Great Peace of Montréal.

In Louisiana, the massacre of colonists at the Natchez post in 1729 set the entire colony ablaze. Several punitive expeditions were led against the Natchez, a great many of whom sought refuge among the Chickasaw, a nation allied with the English. In 1736 and 1740, Governor Bienville set up two expeditions, which also failed. Peace nevertheless returned shortly thereafter, when the Natchez were expelled by the Chickasaw and continued their eastern exodus.

Conclusion (show)

On the eve of the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), Canada and Louisiana formed a “colossus with feet of clay.” A gigantic territory that stretched from the St. Lawrence Valley to the Great Lakes region and the Gulf of Mexico, New France was nevertheless a sparsely settled colony. In fact, in 1750 there were only 55,000 (do we mean European inhabitants??) inhabitants in Canada and not quite 9,000 in Louisiana. The city of Québec was home to only 8,000 people, Montréal to 5,000 and New Orleans to 3,200. Beyond these colonial centres, most of the inhabitants of the “French empire” were Aboriginal allies. Even with their assistance, how could Canadians, so few in number, vanquish the British whose North American colonies contained nearly 1.5 million people?

In 1754, two years after the start of hostilities in Europe, the first signs of tension between French and British colonists emerged in the Ohio region, crisscrossed by traders from Virginia and Pennsylvania. On learning that English soldiers were in the region, the commander of Fort Duquesne, Claude-Pierre Pécaudy de Contrecœur, sent a patrol led by Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville to order young George Washington and his troops to leave the lands claimed by France. The French soldiers were ambushed and Jumonville was killed along with nine of his men.

Thus began a long war during which France won a few victories: Monongahela in 1755, Oswego in 1756 and Carillon in 1758. However, the capitulation of the citadel of Louisbourg, on July 26, 1758, marked the beginning of the end of the French presence in North America. In turn, the forts at Duquesne, Niagara and Frontenac fell into English hands. In September 1759, General James Wolfe seized Québec, and the following year Montréal surrendered. During peace negotiations, Versailles and the royal French government lost interest in its North American colonies. Like Voltaire, the officials of the mother country thought it preferable to preserve French possessions in the Antilles that were much more profitable than Canada and Louisiana, which had drained the royal treasury. Thus, on the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the St. Lawrence valley, the Pays d’en haut and the eastern banks of the Mississippi were ceded to the British whereas the western banks were handed over to the Spanish under the “Pacte de famille”, the family compact concluded by France and Spain in 1761 to ensure the mutual protection of the two kingdoms. This was the end of New France.

Suggested Readings (show)

Balvay, Arnaud. 2006. L’Épée et la Plume. Amérindiens et soldats des troupes de la marine en Louisiane et au Pays d’en Haut. 1683-1763. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval.

Berthiaume, Pierre. 1990. L’Aventure américaine au XVIIIe siècle du voyage à l’écriture. Ottawa: Presses Universitaires d’Ottawa.

Charlevoix, Pierre F.X. 1998. Journal d’un voyage fait par ordre du roi dans l’Amérique septentrionale. Montréal: Presses Universitaires de Montréal (Bibliothèque du Nouveau Monde).

Cook, Peter L. 2001. “Vivre comme frères. Le rôle du registre fraternel dans les premières alliances franco-amérindiennes (vers 1580-1650),” in Recherches Amérindiennes au Québec, vol. XXXI, no. 2, pp. 55–65.

Dechêne, Louise. 1974. Habitants et marchands de Montréal au XVIIe siècle. Paris and Montréal: Plon.

Delâge, Denys. 1989. “L’alliance franco-amérindienne 1660-1701,” in Recherches Amérindiennes au Québec, vol. XIX, no. 1, pp. 3–14.

Desbarats, Catherine. 1995. “The Cost of Early Canada’s Native Alliances: Reality and Scarcity’s Rhetoric,” in William and Mary Quarterly, third series, vol. 52, no. 4 (October 1995), pp. 609–630.

Greer, Allan. 1998. Brève histoire des peuples de la Nouvelle France. Montréal: Boréal.

Havard, Gilles. 2003. Empire et métissages: Indiens et Français dans le Pays d’en haut. 1660-1715. Québec: Septentrion.

Havard, Gilles, and Vidal, Cécile. 2008. Histoire de l’Amérique française. Paris: Flammarion (Champs).

Heinrich, Pierre. 1970. La Louisiana sous la compagnie des Indes (1717-1731). New York: Burt Franklin [1908].

Jaenen, Cornelius J. 1996. “Colonisation compacte et colonisation extensive aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles en Nouvelle-France,” in Alain Saussol and Joseph Zitomersky (eds.). Colonies, Territoires, Sociétés. L’enjeu français). Paris: L’Harmattan, pp.15–22.

Lahontan, Louis Armand de Lom D’Arce, baron de. 1703. Nouveau voyage de M. le baron de Lahontan dans l’Amérique septentrionale. La Haye.

Lamontagne, Roland. 1962. “L’exploration de l’Amérique du Nord à l’époque de Jean Talon,” in Revue d’histoire des sciences et de leurs applications, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 27–30.

Lemaître, Nicole (ed.). 2009. La Mission et le sauvage. Huguenots et catholiques d’une rive atlantique à l’autre. XVIe-XIXe siècle, Paris: CTHS.

Litalien, Raymonde. 1993. Les Explorateurs de l’Amérique du Nord (1492-1795). Sillery: Septentrion.

Margry, Pierre. (ed.). 1879–1888. Découvertes et établissements des Français dans l’ouest et dans le sud de l’Amérique septentrionale, 1614-1754. 6 vol., Paris: Maisonneuve.

Mathieu, Jacques. 1991. La Nouvelle-France. Les Français en Amérique du Nord, XVI-XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Belin Sup.

Nish, Cameron. 1968. Les Bourgeois-gentilshommes de la Nouvelle-France. 1729–1748. Montréal: Fides.

Surrey, N.M. Miller. 2006. The commerce of Louisiana during the French regime, 1699–1763. [1916]. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press.

Villiers du Terrage, Marc de. 1934. Un explorateur de la Louisiane, J.-B. Bénard de La Harpe. 1683-1728. Rennes: Oberthur.

Websites

- Exploration 1497 to 1760:

http://atlas.nrcan.gc.ca/auth/english/maps/historical/exploration/maptopic_view

- La France en Amérique/France in America:

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/intldl/fiahtml/fiahome.html

- Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online:

- Canadiana:

http://www.canadiana.ca/en/home

- New France New Horizons:

http://www.archivescanadafrance.org/english/accueil_en.html

- The Jesuit Relations:

http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/206/301/lac-bac/jesuit_relations-ef/relations-des-jesuites/index-e.html

- La Nouvelle France. Ressources françaises:

http://www.Culture.gouv.fr/Culture/nllefce/fr

- Les cartes de la Nouvelle France:[CP1]

http://rivards.iquebec.com/cartes/cartes_nouvelle_France/cartes_nouvelle_France.htm

- Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America:

http://www.ameriquefrancaise.org/en/

- New France (Canadian Encyclopedia):

http://thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0005701

- Center for Archaeological Studies:

![Map from New Orleans 10 leagues long along the River, with the inhabitant’s landgrant under Mr. Perier |Carte particulière contenant depuis la Nouvelle Orléans 10 lieues de longueur le long du fleuve, avec le terrain des habitans qui fleurissoient sous M. Périer. Anonymous. [ca 1750]. Manuscript map of landgrants established between the bayous and the Fort, whose buildings are detailed Dim. 18.2 cm x 25 cm © Service historique de la défense, archives centrales du département marine à Vincennes, MV SH 71 Recueils R68 numéro 61. www.servicehistorique.sga.defense.gouv.fr Map from New Orleans 10 leagues long along the River, with the inhabitant’s landgrant under Mr. Perier](https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/files/2011/12/New-France_2_4_3_Map-since-the-New-Orleans-10-leagues-long-150x200.jpg)