-

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

- The Explorers

- Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

- Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Economic Activities

- Population

- Daily Life

- Heritage

- Useful links

- Credits

Daily Life

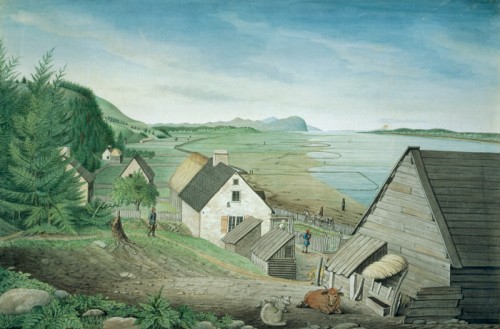

Vernacular Architecture in New France

When settlers arrived in New France, one of their primary concerns was putting a roof over their heads. They had to take the climate, the available materials and their financial resources into account to determine what type of dwelling they would build. Then, depending on the tools they had brought with them, their experience and their ingenuity, they built a home that would provide maximum comfort and security.

In this article, we present the various aspects of domestic dwellings of the New France era. Drawing on archaeological research conducted recently in North America, as well as on archival material, the author describes the types of buildings built in the St. Lawrence Valley, Acadia and Louisiana. Colonial is often the only adjective used to describe the houses in New France, but, in fact, their characteristics varied, depending on the period, the social class and where they were built.

Introduction (show)

The world over, ways of inhabiting a territory depend first and foremost on environmental conditions and the socio-economic status of the occupants. Climate, available materials, the type of soil and many other factors were among the conditions that the colonists of New France had to consider when they built their dwellings, in addition to economic and social issues. These conditions also influenced the form of their settlements. The inhabitants of the St. Lawrence Valley, Acadia and the more remote territories, such as Louisiana and the Illinois country thus tackled their new environment, displaying all their ingenuity in order to survive and attain a certain degree of comfort.

Origins of architectural forms in New France (show)

The first French colonists did not arrive empty-handed in the Americas. They landed on the banks of the St. Lawrence, bringing with them the ancestral traditions that they would strive to pursue, with more or less success, in their new environment. The construction methods they used were subjected to many attempts to adapt them to the North American environment. That is why it is important to go back to the original architectural forms, to gain a better understanding of the scope of their task.

Europe, the cradle of Canadian builders

Although over time, each region developed its own traditions, certain basic architectural forms took shape over the course of the Middle Ages, and in some cases, even earlier. They constituted the beginnings of known forms during the Ancien Régime in France.

The sunken hut appeared in the La Tène period in northern Europe, whereas in Gaul, it only emerged shortly after the Roman conquest. Partly dug into the ground over an area between 5 and 10 square metres, these structures were usually rectangular and of very simple construction: a trench was dug, and at the bottom, on the occupation level, vertical components that formed the framework of the building were inserted in the postholes. There were various construction methods for walls. The advantage of sunken huts was that they could be built quickly and cheaply. This kind of building was suitable for temporary or secondary use, all the more so if the surrounding soil allowed easy, rapid excavation.

The unitary house was the main type of dwelling in the first half of the Middle Ages; even after this period, it continued to be the basis for many regional architectural types. Its ground plan was very simple. In its early form, it had only one room where the fire was sited and which contained everything used for domestic life. Later, a second room would be added, smaller than the first and without a fireplace; it would usually serve as a bedroom or storage space.

The mixed house (or byre house) was less frequent. Out of necessity it sheltered animals and humans under the same roof, each occupying one of the rooms. Like the unitary house, the mixed house underwent an architectural evolution. In its early form, there was no or hardly any partition separating the two sections of the house; at most, at times there would be a drain or a trough. Later, a flimsy partition would be built and would gradually evolve into a sturdier, more durable structure. Finally, the separation was made almost complete with the installation of a ceiling.

Lastly, we should mention the existence of the fortified house, a model resulting from the establishment of large agricultural domains where the production of surplus required larger storage facilities and better organization of space. Because it possessed a quadrangular plan, it was easier to enclose the farm in a compound: a wall often enclosed empty spaces between ancillary buildings. It could also be fortified by a gate or corner towers.

The influence of the natural environment

For the most part, the natural environment determined construction methods, particularly with regard to the choice of materials available in certain regions, such as earth, stone and wood. For example, in places where the soil layer was thick and stones were in scarce supply, people chose earthen construction whereas on sites where the parent rock was shallow, people would use fieldstone they gathered when working in the fields to build the walls of the dwelling. Furthermore, both types of construction, earth and stone, are encountered in a same region, depending on intraregional environmental variations. The same is true for the use of roofing materials, even though thatch continued to be the most popular.

Haute-Normandie, one of the principal historical regions of France from which many colonists originated, is the land par excellence of timber-frame and earthen rough casting construction, both for the hovels on humble farms and manors of tenant farmers. In this region, dwellings did not originally have any upper storeys; the foundations were of stone, the spaces between wall posts were in-filled with wattle and daub, brick or cob, and the hipped gable roof, covered with thatch. The doors and windows were located on the south face of the house, as the northern face was nearly always blind.

In Île-de-France and Orléanais, two other French provinces from which a significant contingent of colonists originated, dwellings were based on the unitary house model, to which people could add more rooms as their needs expanded. This house, with a bread oven beside a gable wall, has an extended, sturdy appearance . It does not have much light: its only openings are one door, one window and an access dormer on the main facade. Limestone continued to be the most often used material for construction in Île-de-France and Orléanais. This was mainly fieldstone removed from the fields or taken from small, nearby quarries, although cut stones were used for the cornerstones of buildings.

However, earth and stone did coexist in many regions, such as Beauce, where a thick layer of limestone prevented stone quarrying. Although stone was present everywhere in Île-de-France, earth walls were found in some areas, where wetlands made the ground unstable. This type of dwelling was thus much more resistant to ground motion and variations in temperature and humidity than its counterpart made of stone. Its gable roof was nearly always of thatch, although half-round tile was used for the same purpose, especially for seigneurial and bourgeois houses. Slate was less widespread.

In Poitou and Charentais, where a significant portion of the colony’s population originated, the construction techniques varied according to the landscape. Thus, a house’s foundations were often reduced to their simplest expression, when they existed. People were content to dig down to the parent rock and, since it was usually close to the surface, the foundations never exceeded one metre. Nevertheless, in marshlands there was no infrastructure, since the nature of the soil prevented excavation. Earth houses were thus built directly on the ground, whereas stone houses were set on a shallow foundation of stones bound with loam mortar.

Stone wall construction techniques varied considerably. Preserved on clearing fields of stone, the stones were arranged to form a batter, or slope, the largest stones being used at the base of the building. In this way, two faces were formed and a fill of pebbles or stones and earth was placed between them. Earth wall construction techniques were just as numerous. These include timber-frame construction, in which the walls were insulated by lime or earth plastering, but other methods were also featured. A light wood frame could be filled, or bricks of dried mud could be formed in wooden moulds, to build the wall. Mixtures of earth would also vary, because both wattle-and-daub and “bouseli” (dung mixed with earth) were used.

Finally, the prevailing situation for roofing was the same as it was in the other regions we have explored to date. The use of vegetation was clearly predominant. Slate was only a recent change, encouraged by the authorities to prevent fire. Tile was also used, including half-round tile in the south of the region.

The influence of the socio-economic environment

An owner’s socio-economic status was demonstrated through myriad construction methods and dwelling types that also varied according to the region and the availability of materials.

One of the first signs of this status lay with the choice of construction material. In places where stone and earth coexisted, the choice would be stone, to amplify the house owner’s status because of its added value. Indeed, cut stone construction required much greater technical and pecuniary resources than erecting an earth building: it required quality materials that were not necessarily available in the immediate region, not to mention the skilled labourers needed to cut the stones and erect the walls.

At the other end of the spectrum, the semi-underground sunken hut, usually designed to be used as an ancillary building on the dwelling site, as a shelter to lodge servants or hired labourers, sometimes slaves, or by the owner who would live there for a certain period of time, was not very costly since it could be built quickly and it was easy to obtain the few materials required locally.

Haute-Normandie was an exception to the rule, because even seigneurial manors were built of earth and timber. The socio-economic status of owners was thus demonstrated through other characteristics, such as the addition of one or two storeys, the plastering of outer walls, the replacement of a thatched roof with a tiled or slate roof or through the choice of floor covering material. It should be emphasized that the characteristics illustrating material affluence also existed in a large portion of Ancien Régime France, except for the multi-storey house, already present in Provence during the Middle Ages among all social classes.

The socio-economic aspect of the architecture was also apparent in the ground plan of farms. For example, the quadrangular plan of a farm attested to the farmer’s affluence, an obvious sign that the establishment was generating a surplus, all the more so if it was enclosed by walls and a gate and corner towers had been added, as in the case of the fortified manor.

Dwelling in the St. Lawrence Valley (show)

The early buildings

The sunken hut, one of the most basic forms of dwelling and the oldest in Europe, was used in New France, as attested to by the remains of a semi-underground dwelling discovered in La Prairie, a small town in Montérégie. These remains included the vestiges of a white pine floor, located at 1.40 metres below the surface of the natural soil, as well as the vestiges of posts planted in the earth, marking the site of two walls, the base of a third one, made of vertical planks and lastly, the traces of an open hearth. Furthermore, the absence of nails suggests that the hut had been covered with thatch. It was built in the soft ground of the primitive village in about 1670 and probably used until the 1680s. The artifacts and the biofacts uncovered during the archaeological dig of this sunken hut leave no doubt as to the fact that domestic activities occurred there, probably until a sturdier house was built for the owners.

This form of dwelling is rare in the St. Lawrence Valley, because the abundance of timber enabled most of the newcomers to use this material to build less rudimentary dwellings. Thus, one of the oldest dwellings of European origin to have been revealed was discovered on the Côte-de-Beaupré, in the Cap-Tourmente National Wildlife Area. It belonged to the Petite-Ferme farming operation, built in 1626 on the orders of Samuel de Champlain and destroyed two years later by the Kirke brothers. The dig revealed a few walls of timber-frame construction whose posts had been embedded in the ground and in-filled with rammed earth, an architectural form closely akin to that of Normandy.

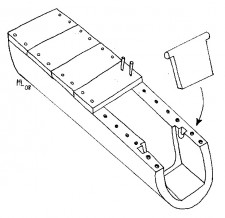

Colombage walls supported on a low wall plate or sill, resting on a stone foundation, were more frequently used during the 17th and 18th centuries. The posts were narrowly spaced (between 15 and 40 cm) and the spaces between them were filled with small stones, called “pierrotage (stone and mortar)”. Nevertheless, colombage walls could sometimes be filled in with brick in regions where brick was available or, with wood, according to the post and sliding piece technique.

Other architectural practices using timber were featured during the French Regime, some losing popularity over time while remaining popular in rural or colonial areas. This was true of the palisade wall construction, called “upright picket construction,” in the St. Lawrence Valley. These walls, made of pickets or posts, were covered with clay or daub to make them impermeable. The tree trunks were usually squared inside the dwelling while the joints between the posts remained apparent outside: the interstices were chinked with clay or mortar. These upright picket buildings were among the most modest dwellings, but the technique was also used for certain ancillary buildings.

A variant of this technique was “post on sill construction”, where the vertical components were supported on a low wall plate, or sill, laid on a stone foundation. Archaeology has revealed a house built in this manner on Île aux Oies around the mid-17th century. With its stone foundations on top of which lay wood fibres and the remains of the base of a corner post, this unitary house, which had been expanded with a gable wall, attests to typical construction methods for modest dwellings, which required only a few specialized resources. In addition to possessing the characteristics of post on sill, the remains showed that the house had been equipped with a clay chimney and that thatch was the basic roofing material.

Lastly, the pièce sur pièce technique, which appeared in the second half of the 17th century, cannot be overlooked. It involved stacking pieces of timber horizontally, without benefit of pickets or colombage to frame them. The term “pièce sur pièce,” as used in the construction markets during the French regime, means that the stacked components were of squared timber, although unsquared timber and logs were also used. The pieces were usually dowelled and the corners showed dovetailed or right angle notching. The joining notched corners rested on a stone or brick foundation.

Stone construction was to be found mainly in urban areas, at least until the second quarter of the 18th century. Given the shortage of stonecutters in the colony, cut stone was seldom used, except for the cornerstones of the main walls. Rough hewn stone (or rubble stone) was used bounded with mortar arranged in two faces. The space left between the two walls (or faces) was filled with the leftover stones that were embedded in the mortar. These urban buildings often had a second storey that was built of colombage, covered with a planked roof.

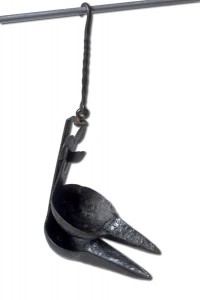

In the early years of the colony, the hearth was the preferred heating system in these houses. Fitted on a gable wall of the dwelling, but sometimes located in the centre, its chimney could be made of clay in the homes of less affluent settlers, but colonists preferred stone chimneys. However the hearth was not the most efficient heating system, because its heat, intense near the flame, quickly subsided as soon as you stepped away from the fire. That is why the stove began to appear in some residences starting in the 17th century, even though it was a luxury. The first stoves were made of brick, covered with a cast-iron plate or sheet iron in the homes of the less affluent. Such rudimentary facilities continued to be found in the small houses of working-class suburbs and neighbourhoods at the dawn of the 19th century, as attested to by the results of archaeological excavations in Québec City, where hollow clay bricks associated with these stoves resurfaced.

Adaptation to the environment

Some construction techniques seem to have been abandoned quickly by residents of the St. Lawrence Valley. For example, colombage and cob fill or colombage and stone fill houses tended to disappear with the approach of the 18th century, as did upright picket, earthfast or on sill, or post and sliding piece dwellings. These techniques were then only used in dwellings for the less affluent or ancillary buildings, while pièce sur pièce became increasingly popular, especially in rural communities. Indeed, because the thickness of the timber served as insulation, pièce sur pièce houses proved much less energy consuming and more comfortable than other forms of construction.

Comfort was enhanced by the growing popularity of heating stoves in thatched cottages, both in towns and rural areas, starting in the 1730s-1740s, after the Forges du Saint-Maurice were built. Indeed, in addition to diffusing the heat stored in the stove’s cast iron, the smoke exhaust pipe spread the heat along its length. However, the hearth, in the kitchen, was not abandoned, as it continued to be used for cooking food.

Country and city

Urban and rural houses evolved very differently during the French regime, for the most part as a result of Intendant Dupuy’s ordinances, of 1721 and especially that of 1727, which aimed to more strictly regulate the construction of houses in towns and the suburbs to reduce the risk of fire.

In rural areas, there were very few mixed houses (or byre houses) that sheltered both humans and animals. Instead, the unitary house predominated, consisting of only one room, sometimes expanded with a second room, an attic and its cellar, a simple hole dug under the floor where perishable foodstuffs were stored, such as lard.

For erecting walls, colombage was relatively popular in the 18th century, but its use declined over the years and was overtaken by pièce sur pièce, a construction technique that was easier for unskilled labourers. Both for colombage and pièce sur pièce, the lower elements of the structure usually rested on a single bed of stone or a relatively crude foundation, whose degree of simplicity did not require the care of a skilled artisan. Archival documents mention the presence of a few “cabanes” (huts) made of upright pickets, but such dwellings were rare. The gable roof was covered with planks, shingles or thatch. Lastly, the house was heated by a hearth whose chimney was usually made of stone, but sometimes of clay in the homes of the poor. In such cases, a mason would sometimes be hired to build the chimney—essential to the dwelling’s safety.

Over time, stone dwellings gained popularity in the countryside, but would never supplant the small frame house, well suited to the climate and much less costly to build.

The case of towns was different, because urban architecture evolved according to parameters defined by the fire hazards. Prior to 1673, the year of the promulgation of a series of regulations aiming to reduce the risk of fire, the number of colombage houses in the towns and in rural areas was about the same. However, between 1660 and 1727, in Québec and in Montréal the respective proportion of stone houses was already 37 percent and 31 percent, although this type of house represented only 6 percent of all rural dwellings. Lastly, between 1727 and 1760, the cities showed a strong increase in stone houses, notably in the walled city that the new construction standards of 1721 and 1727 concerned in particular.

http://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca” width=”225″ height=”300″ class=”size-medium wp-image-3124″ />

http://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca” width=”225″ height=”300″ class=”size-medium wp-image-3124″ />Guillaume-Estèbe House

Although houses constructed of colombage, upright pickets and other techniques using wood were found in urban environments from the beginnings of the colony, stone soon came into use where the ruling classes, the higher clergy and the merchants lived. The observation is not surprising, for the construction of this kind of house was costly: materials, the excavation work for the foundations, the stone cutters, the labourers who made the mortar and many others had to be paid for.

Thus, as a result of the ordinances regulating construction in urban areas, the storey of timber or colombage in the urban house disappeared. A dwelling, that now usually had at least one storey above the ground floor, was now entirely made of stone and was built over a vaulted cellar. It had two gable walls inside in which chimneys and fireplaces were inserted. The gable walls had to be much higher than the roof, thus becoming firebreaks. The gable roof was covered with two thicknesses of planks, as shingles and thatch were now prohibited by regulation. It should be mentioned that the wood structure of the roof had been streamlined to make it easy to demolish in the event of fire.

Another special feature of the urban house was associated with the obligation to build sanitary facilities to enable residents to dispose of their waste elsewhere than in the street. In the dwellings of the affluent, latrines were built in the cellar: a hole was excavated and carefully lined with stone; and in some cases, drainage devices were built. Elsewhere, a ditch was dug, sometimes lined with planks inside a hut in the back yard of the house.

Regional variations

Three urban centres developed on the banks of the St. Lawrence during the French regime. In the cities of Québec, Trois-Rivières and Montréal, having been founded on different dates and being separated from each other by significant distances, the architecture showed some variation, lending each a distinct appearance.

Not surprisingly, the physical environment of these urban areas dictated some of the architectural forms that prevailed there. This is the case for Québec, which, thanks to its quarries located on the periphery* (see the endnote), always had the largest proportion of stone houses throughout the French regime. Because of this nearby resource, it was easier for the residents to comply with the fire-prevention ordinances issued. From a proportion of 55 percent from 1660 to 1727, buildings made of wood declined to 24 percent after this period. A large part of these wood houses had at least one storey above the ground floor, or 40 percent from 1660 to 1727.

The landscape radically changes along the St. Lawrence River to Trois-Rivières, where stone is rare in the immediate environment. Perhaps that accounts for limited impact of the ordinances on architecture in the market town, but the fact remains that most domestic construction was of wood. Whether colombage or pièce sur pièce, these houses only had a ground floor.

More distinctions existed in Montréal, which responded much more slowly to the ordinances. Although stone ultimately displaced wood in the preferences of Montréalers, it did not surpass wood until around 1727, where it was found in 51 percent of buildings. Until then, in Montréal, the houses were mainly of colombage or pièce sur pièce, of which 72 percent only had a ground floor.

Beyond these differences in the choices of construction materials, Québec and Montréal had in common wood as the dominant construction material in the suburbs. In both cases, wood continued to predominate until the end of the French regime, although stone gained in popularity in Québec starting in 1727. Indeed, during this period in Montréal, colombage timber construction reached a proportion of 56 percent, whereas pièce sur pièce construction accounted for 86 per cent.

Social status

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”210″ height=”300″ class=”size-medium wp-image-3330″ />

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”210″ height=”300″ class=”size-medium wp-image-3330″ />Archaeological remains of a poteaux-sur-sole building, Old Mobile (Alabama)

During construction of a dwelling, the choice of construction materials and the ground plan revealed further information about the socio-economic status of the owners. As for the materials, it has been noted that the oldest settlements were mainly constructed of wood, using techniques requiring few expenses. For example, earthfast houses were preferred by colonists in a hurry to settle in anticipation of better times. This was also the case for semi-underground dwellings. As economic conditions improved, the dwelling would be built on a foundation, colombage timber-frame construction gained popularity and brick heating stoves accompanied the hearth. Multi-storey stone houses gradually replaced wood buildings in cities when resources permitted; meanwhile, they gained popularity in the rural areas.

In addition to the choice of construction materials, the plan of the building revealed much about the wealth of its owner and the image he wished to project. Fort Senneville, located on westernmost tip of the island of Montréal, constitutes a very good example of the use of architecture as means of affirming social status. Between 1702 and 1704, Jacques Le Ber de Senneville had a stone fort erected that contained defensive stone walls, bastions, a manor house, appendages, latrines and a water tank. The complex was devoted to the protection of the region’s residents, but according to the historical documentation, it was mainly used as a trading post until 1724. It later housed a grain miller and a farmer and a garrison of militiamen in 1747 and in 1748, and was then used as a general store following a period of abandonment. Finally, Fort Senneville was destroyed by fire during the American invasion of 1776.

Archaeological excavations conducted in 2004 attempted to shed light on the real purpose of the fort, because a simple palisaded building could very well have replaced this relatively large stone building. Furthermore, scarcely any trading materials were uncovered in contexts associated with the trading post era. Lastly, although its architecture argues in favour of the fort’s defensive nature, it is strange to note that its construction took place in 1704, during a period of calm, following the Great Peace of Montréal (1701), and that its site on the west end of the island of Montréal was of secondary strategic military interest. However, its quadrangular plan and its walls enclosing the fort buildings lead us to note that the builders opted for a classical architectural model, highly coveted in metropolitan France. Thus, it appears that the choice of materials and the building plan rather had the purpose of restoring the credibility and prestige of its owner following significant financial difficulties.

These examples show that as the socio-economic status of an owner improved, the use of stone increased and the architecture of a building would be more complex, while wood and the unitary house were abandoned.

*Stone houses not only required stable material such as limestone, sandstone or granite, but the stones had to be bound with mortar. As for quarries, the lowlands of the St. Lawrence contain limestone deposits that the inhabitants of New France soon developed both for the stone and the lime they produced, essential for good mortar. Thus, a variety of quarries were found near cities, along with limestone ovens, beginning in the second half of the 17th century.

Meanwhile, in Acadia (show)

The Belle-Isle marsh in Nova Scotia was home to Acadians who established farming operations there during the second half of the 17th century. Archaeological excavations conducted in the region led to the discovery of many architectural remains associated with the dwellings of the first colonists which have made it possible to better understand the design of rural dwellings found there during that era.

The analysis of the data collected in the field made it possible to draw up a relatively accurate sketch of the typical dwellings of Belle-Isle marsh. Thus, the first Acadians built small rectangular houses on fieldstone foundations with pièce sur pièce or colombage and cob walls. The sole room was heated by a hearth built against a gable wall and equipped with a clay chimney, and a brick backplate. A daub bread oven, in the shape of a dome was built against the same gable wall, but outside the dwelling. The building was covered with a thatch gable roof.

Inside the house there was a shallow cellar, about 0.60 metre deep, that sometimes occupied half the surface area of the dwelling. It was dug under the floor, which was sometimes built over a sole-piece of tree trunks. The surface of the walls was covered with stucco.

… in Louisiana (show)

The houses of Fort Toulouse, in Alabama, an early archaeological example

The chosen archaeological example illustrates the evolution of domestic architecture in this area of New France that would be strongly akin to the construction techniques used by the first Acadians to arrive in Louisiana following the Deportation.

From 1717 to 1763, Fort Toulouse played a role in maintaining the French presence and the expansion of Louisiana in the southeastern United States. The geographical situation of the fort, at the head of the Alabama River, proved highly strategic, from the point of view of both the expansion of French influence inland and that of trade, in particular, the fur trade. Despite these advantages, the remoteness of Fort Toulouse and the difficult life that the troops experienced there caused dissension among them, which took the form of desertions and mutinies. By way of a solution, the colonial leaders encouraged the establishment of a settlement of civilians outside the walls of the fort. The families formed by soldiers marrying French women settled there, thereby establishing the Alabama Post.

Excavations carried out on the site of the Alabama Post uncovered vestiges of dwellings dating from the occupation of these French families. Although farming has altered the architectural remains associated with occupation during the French regime, the evidence gathered sketches a profile of the architecture of the dwellings, associated with the early settlements in the St. Lawrence Valley, before they had adapted to the harsh Canadian climate. Indeed, the vestiges show a house perhaps consisting of a single room at the outset and to which a second room may have been added at one end. The walls were built using the earthfast technique where the interstices were filled with cob. However, the dig did not reveal evidence of the heating system or the roof composition.

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”129″ height=”200″ class=”size-thumbnail wp-image-3329″ />

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”129″ height=”200″ class=”size-thumbnail wp-image-3329″ />Archaeological remains of an early 17th century soldiers quarters built using the pieux-en-terre technique, Old Mobile (Alabama)

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”150″ height=”98″ class=”size-thumbnail wp-image-3333″ />

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”150″ height=”98″ class=”size-thumbnail wp-image-3333″ />Aerial view of the trenches in which stood a pieux-en-terre structure in Old Mobile (1702-1711), Alabama.

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”150″ height=”99″ class=”size-thumbnail wp-image-3338″ />

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”150″ height=”99″ class=”size-thumbnail wp-image-3338″ />Excavations of the construction trenches of a small square poteaux-sur-sole building at Port Dauphin (1702-1725), Alabama.

Other archaeological digs conducted in Mobile, Alabama have revealed numerous vestiges of dwellings dating from the early 18th century. Two construction techniques were identified: earthfast and post on sill. The first is associated with small one-room houses that served as a camp for Mobile garrison troops, while the second included dwellings with several rooms, probably occupied by the civil population.

The Creole house and the arrival of Acadians in Louisiana

Upon arriving in Louisiana, the Acadians entered into contact with the existing Creole culture of the French already living there, partly influenced by metropolitan French culture and that of the West Indies. The Acadians adapted this culture, retaining certain elements that met their needs.

Adaptation occurred through the gradual transformation of buildings constructed by the Acadians of Louisiana. The first dwellings the Acadians built were constructed using the earthfast technique, in which walls were surmounted by a gable roof covered with palmetto thatch. However, posts were soon replaced by cypress planks, still driven into the ground and arranged as a palisade, while bark was the roofing material.

Around the end of the 18th century, “Cajun” domestic architecture took on itsdefinitive form through its borrowings from Creole technique and their adaptation to age-old traditions. The wall posts were set on a heavy sill supported above the wet ground by cypress pillars, which would later be replaced by brick pillars. The spaces between the posts were in-filled with rough casting made of daub, the front and rear windows were carefully aligned to improve ventilation. The porch, or veranda, extended along the facade of the house.

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”202″ height=”300″ class=”size-medium wp-image-3337″ />

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”202″ height=”300″ class=”size-medium wp-image-3337″ />Exterior bousillage of the LaPointe-Krebs House in Pascagoula, Mississippi

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”203″ height=”300″ class=”size-medium wp-image-3336″ />

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/” width=”203″ height=”300″ class=”size-medium wp-image-3336″ />Detail of the LaPointe-Kreb House bousillage in Pascagoula, Mississippi

The interior of the house could sometimes contain two rooms, but most often only one, and the gable roof made it possible to build an attic. The source of fire, for cooking or for heat, was always the hearth and the chimney, made of clay. This material would later be replaced by brick, as would the pillars, after the house had been insulated from the ground. Lastly, the dwelling would have a gable roof, a typically French feature that attested to the rejection of the “hipped roof,” typical of Creole architecture. However, French roofing would undergo a slight transformation when it was extended over the veranda of the façade to provide precious shade.

… and in lllinois country (show)

Having arrived in the course of the 18th century, the colonists of Canadian origin were able to adjust certain architectural conditions that were more suitable to the relatively mild climate of the greater Mississippi region than to the more difficult environment of the banks of the St. Lawrence. Furthermore, the Louisianais who settled in the Illinois country most likely brought their store of knowledge that also influenced the architectural landscape.

The earthfast technique was used in early construction, but humidity and risk of flooding soon required builders to review their techniques to make them more sustainable. People then opted for post on sill, insulated from the ground by a stone foundation. The space between the posts was filled with small rubble (stones) embedded in mortar or mud (colombage and stone), or a mix of clay and organic materials (colombage and cob).

Like the Acadian house of Louisiana, the dwelling in the Illinois country had verandas that wrapped around two or four sides of the building. The porch was protected from the sun by adding an extension to the French style gable roof or the truncated hipped roof that was supported by posts embedded in front of the veranda. This architectural element likely indicates Creole influence. The roof was usually covered with cedar shingles.

![French house in Illinois Country, detail from the Ohio River map [Carte générale du cours de la rivière de l'Ohio…], ca. 1796, Victor Collot | Cartes et plans, GE A 664, Bibliothèque nationale de France French house in Illinois Country, detail from the Ohio River map [Carte générale du cours de la rivière de l'Ohio…], ca. 1796, Victor Collot](https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/files/2012/04/New-France_5_5_French-house-in-Illinois-Country-500x394.jpg)

French house in Illinois Country, detail from the Ohio River map [Carte générale du cours de la rivière de l'Ohio…], ca. 1796, Victor Collot

Although at the outset, it likely only had one room, like most of the early dwellings built by the colonists, the Illinois house evolved so as to have a few partitions on the ground floor, while preserving an attic that could be inhabited. Thus, a typical house was only a storey and a half, including the attic. The inhabited areas were heated by a stone hearth that was not always used for cooking, because many examples of colonial houses in Illinois country had an outdoor kitchen.

Conclusion (show)

The study of architecture in New France reveals that adaptation to a new physical and human environment required more than just a few years and that a period of transition was necessary to achieve an ideal way of living. The gradual abandonment of certain construction techniques in the St. Lawrence Valley and their improvement in milder climates, as in the Illinois country and in Louisiana, shows, however, that the inhabitants of New France demonstrated ingenuity in making these new lands more welcoming.

Suggested readings (show)

AUDET, Bernard, 1990 Avoir feu et lieu dans l’île d’Orléans au xviie siècle. Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, coll. “Ethnologie de l’Amérique française”, 1990. 271 p.

BOITHIAS, Jean-Louis and Corinne MONDIN, 1979 La maison rurale en Normandie. 1. La Haute-Normandie. Contribution à un inventaire régional. Nonette, éditions CRÉER, “Les Cahiers de construction traditionnelle,” 90 p.

CHAPELOT, Jean and Robert FOSSIER, 1985 The Village and House in the Middle Ages. Translated by Henry Cleere. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press,.

CÔTÉ, Hélène, 2008 “L’architecture vernaculaire dans l’aménagement du territoire en Nouvelle-France: médium de communication ou adaptation au milieu?” in Christian Roy and Hélène CÔTÉ (Eds.) Rêves d’Amériques: Regard sur l’archéologie de la Nouvelle-France. Québec: Association des archéologues du Québec, coll. “Hors série,” (pp. 141-168.

2005 Archéologie de la Nouvelle-Ferme et la construction identitaire des Canadiens de la vallée du Saint-Laurent. Québec: Association des archéologues du Québec, coll. “Mémoires de recherche,” 2, 198 p.

2003 Paléohistoire, Moyen-Âge et modernité. Résultats de l’intervention archéologique de 2001 sur les sites BiFi-23 et BiFi-12 à La Prairie. Québec: Célat, Université Laval, 115 p.

DE BILLY-CHRISTIAN, Francine and Henri RAULIN, 1986 L’architecture rurale française. Corpus des genres, des types et des variantes. Île-de-France et Orléanais. Paris: Berger-Levrault, 269 p.

DECHÊNE, Louise, 1988 Habitants et marchands de Montréal au xviie siècle. Montréal: Les Éditions du Boréal, 532 p.

GAUTHIER-LAROUCHE, Georges, 1974 Évolution de la maison traditionnelle dans la région de Québec. Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, coll. “Les archives de folklore,” 15, 315 p.

GUIMONT, Jacques, 1996 La Petite-Ferme du cap Tourmente. De la ferme de Champlain aux grandes volées d’oies. Sillery: Septentrion, 230 p.

GUMS, Bonnie L., 2002 “Earthfast (Pieux en Terre) Structures at Old Mobile,” in Gregory WASELKOV (ed.) French Colonial Archaeology at Old Mobile: Selected Studies. Historical Archaeology, volume 36, no 1, pp. 13-25.

JEAN, Suzanne, 1981 L’architecture rurale française. Corpus des genres, des types et des variantes. Poitou, pays charentais. Paris: Berger-Levrault, 297 p.

LAVOIE, Marc, 2008 “Un nouveau regard sur le monde acadien avant la Déportation. Archéologie au marais de Belle-Isle, Nouvelle-Écosse,” in Christian Roy and Hélène CÔTÉ (eds.) Rêves d’Amériques: Regard sur l’archéologie de la Nouvelle-France. Québec: Association des archéologues du Québec, coll. “Hors Série,” 2, Québec, pp. 70-95.

LÉONIDOF, Georges-Pierre, 1987a “Les maisons, 1660-1800,” in Louise DECHÊNE (ed.) Atlas historique du Canada. Vol. I: Des origines à 1800. Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, pl. 55.

1987b “La maison de bois,” in Louise DECHÊNE (ed.) Atlas historique du Canada. Vol. I: Des origines à 1800. Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, pl. 56.

LÉONIDOFF, Georges-Pierre, Micheline HUARD and Robert CÔTÉ, 1996 La construction à Place-Royale sous le Régime français. Québec: Les Publications du Québec, coll. “Patrimoines,” dossier no 98, 477 p.

MARTIN, Paul-Louis, 1999 À la façon du temps présent. Trois siècles d’architecture populaire au Québec. Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, coll. “Géographie historique,” 378 p.

MOUSSETTE, Marcel, 2009 Prendre la mesure des ombres. Archéologie du Rocher de la Chapelle. Québec: Les Éditions GID, 315 p.

1983 Le chauffage domestique au Canada, des origines à l’industrialisation. Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, coll. “Ethnologie de l’Amérique française,” 316 p.

ROYER, Martin, 2007 “Le fort Senneville, un poste de traite (?),” Québec: Association des archéologues du Québec, Archéologiques, 20, pp. 16-27.

SHELDON Jr, Craig T., Ned J. JENKINS and Gregory A. WASELKOV, 2008 “French Habitations at the Alabama Post, ca 1720-1763,” in Christian Roy and Hélène CÔTÉ (eds.) Rêves d’Amériques: Regard sur l’archéologie de la Nouvelle-France. Québec: Association des archéologues du Québec, coll. “Hors série,” 2, (pp. 112-126.

WASELKOV, Gregory A., 1991 Archaeology at the French Colonial Site of Old Mobile (Phase 1: 1989-1991). Mobile: University of South Alabama, Anthropological, 1, 212 p.

Web Links (show)

Center for Archaeological Studies – University of South Alabama

http://www.southalabama.edu/archaeology/center.html

Center for French Colonial Studies

http://depts.noctrl.edu/cfcs/

Colombages verronais (in French only)

http://www.vernon-visite.org/maisons/fr/hourdis.htm

De pierre, de bois, de brique. Histoire de la maison au Québec (in French only)

http://www.maisonlamontagne.com/accueil.asp

Elizabeth M. Scott, Excavations and Research at Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, and related French Colonial Sites

http://lilt.ilstu.edu/emscot2/relatedsites.html

Fort Toulouse & Fort Jackson Living History Groups

http://www.fttoulousejackson.org/FrenchHabitations.htm

The Canadian Encyclopedia – Architectural History: The French Colonial Régime

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/articles/architectural-history-the-french-colonial-regime

Louis Bolduc House, Missouri

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Bolduc_House

Ste. Genevieve, Missouri

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ste._Genevieve,_Missouri