-

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

- The Explorers

- Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

- Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Economic Activities

- Population

- Daily Life

- Heritage

- Useful links

- Credits

Daily Life

Communications

In this day and age of planes and automobiles, it may be difficult to imagine what travel involved 400 years ago, before the invention of the piston engine or even the steam engine. In New France, the energy of wind and currents, draught animals, or human beings working oars was the only way of providing means of travel for people, goods and information.

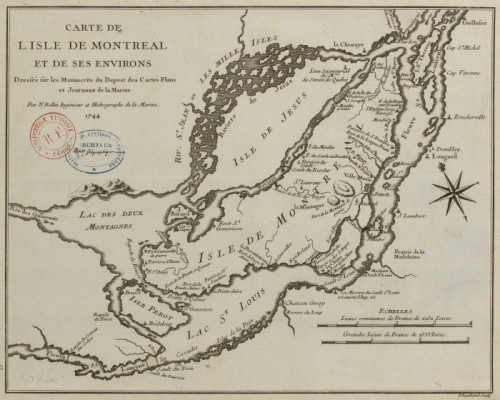

To send a letter from Versailles to Detroit, for example, first it had to be sent by horse or carriage to the ports of La Rochelle or Bordeaux. Then followed the long trans-Atlantic voyage aboard sailing ships. On arriving at Québec, the missive was placed in a smaller craft, or in winter, a sleigh: no rideable road linked the capital with Montréal before the end of the 1730s. Upstream of Montréal, the canoe became the favoured mode of transportation when the river was ice free.

The following article presents means and networks of communication in New France. It reveals the ways in which in royal decrees and the reports of colonial administrators, the correspondence and merchandise of businessmen and personal letters of the colonists were conveyed throughout the Atlantic region and on the continent. In cities or in rural parishes, the more or less ritualized use of bells, drums and proclamations, as well as word of mouth, provided means of circulating information.

Introduction (show)

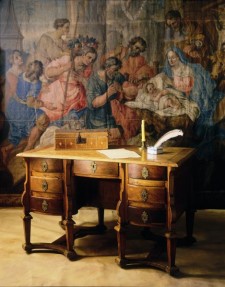

L’art d’écrire, plate II from the Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, 1762-1772, by Diderot et d’Alembert

Communication was central to the making of New France. Like other ancien-régime societies, New France was characterized by a culture with strong written and oral components, a “textual-settler culture” to borrow Friesen’s terminology. The common people lived their daily lives in a culture ostensibly dominated by oral media when, in fact, powerful written elements structured their lives. Books of scripture and catechisms, marriage contracts, seigneurial rent payments, merchant’s registers, ordonnances emanating from a colonial official, or written documents kept in a chest with other valuables, all had a direct bearing upon the lives and livelihood of the population.

That the written and oral worlds worked in tandem in New France is obvious. Our approach is to interpret how these two worlds worked together by examining communication at various scales of social life.

First, New France was a colony tied to the French métropole by a web of transportation and communication networks stretching across the Atlantic and encompassing Europe, Africa and America. Second, New France was a continental reality, competing and interacting with the English colonies that extended from Detroit to New Orleans and outward into the pays d’en haut, around the Great Lakes towards the Prairies and the foothills of the Rockies. And, finally, if the matter is cut down to the bone as in 1759, New France can be examined in a more limited social scale as a region of settlement occupying a single valley, the St. Lawrence, over a distance of a few hundred kilometres.

Communication was not the same in each of these three situations, nor could it be. Distinctive means, methods, and patterns of communication were fashioned to meet the challenge of keeping in touch. Each communication pattern was lodged within a particular scale or geographic setting of social life. My job here is to tease out the pattern and thereby achieve a better understanding of communication in New France in accordance with Lasswell’s now famous line of questioning: Who said what, to whom, through which channel, and with what effect.

Transatlantic Perspective (show)

Viewed from the loftiest of the three scales, postal communication was an interlocking system embracing New France, France, and the world beyond and between. The backbone of the system was ocean navigation, which distributed French power and mail to various points of the globe.

Navigational Infrastructure

During the 1640s and 1650s, there were usually three to four vessels putting in at Québec’s harbour each year. That number increased during the 1680s, but fell at the end of the century. During peacetime from 1713 to 1743, traffic to Québec rose again to up to 10 vessels annually; the rise is pronounced during the two succeeding periods to an average of 18 vessels in the late 1740s and 25 per year the following decade.

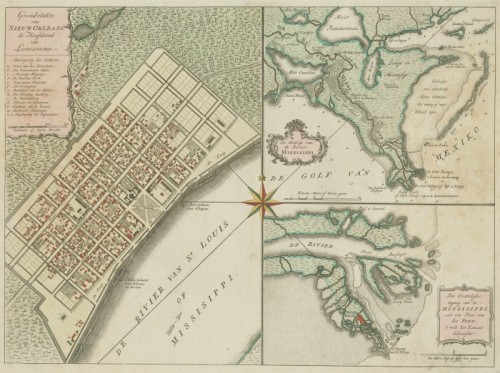

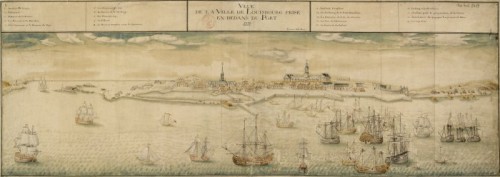

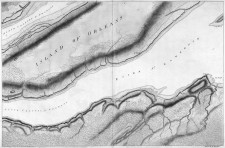

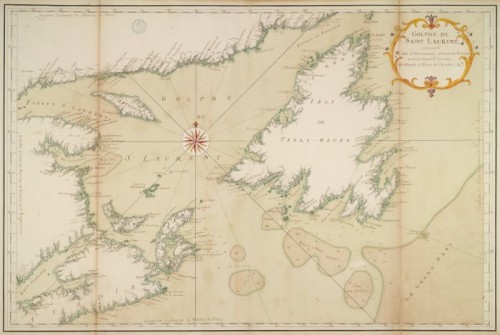

Established after the abandonment of Placentia in Newfoundland, yet strategically perched near the entrance of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Louisbourg was integral to the rise of shipping in the French Atlantic. Far busier than Québec, Louisbourg was visited by 130 to 150 ships per year during the 1730s. By contrast, there was less navigation and hence cargo going in and out of New Orleans, the capital of Louisiana. Ships could sail fully laden up the Mississippi, but there was not always something to take back. Of course, the purpose of sailing to and from Louisiana may have had very little to do with the local economy and much more to do with the potential for illicit trade with the neighbouring Spanish colonies.

The growth of French shipping was the result of increased trade in colonial produce from New France (furs, wood, wheat, fish) and from the Antilles, in particular from Saint-Domingue (sugar). The French merchant marine grew apace from 750 vessels in 1688 to 1800 by 1738. France built up its military strength in New France at Louisbourg and Québec, in the Western interior, and, to some extent, in New Orleans, in order to buttress commercial investment. Geopolitics was the second factor of increased transatlantic shipping.

As the early 18th century wore on, there were more French ships putting out to sea. French ships were to be found rounding the Horn toward the Pacific versant of South America. They played a primary role in the slave trade out of Africa. The French pushed around the southern tip of Africa and, via Mozambique, Mauritius and Île de Réunion, into the Indian Ocean. They were anxious to tap into the market for French wine in the British colonies of India. Navigation had the effect of integrating French space on a global scale. To paraphrase I.K. Steele (cited in Banks2002), the ocean waterways served as commercial boulevards rather than castle moats.

Navigation infrastructure was devised and geographic knowledge accumulated from around the world. 18th-century maps of the west coast of France testify to steps taken to service and protect global trade at home. At least five fortified positions defended the channel up the Charente River to the French naval base of Rochefort, which was itself similarly protected. The place names of small communities and agglomerations bear witness to the importance of shipping and trade: Port-des-Barques on the Charente is a small agglomeration. Nearby is Anse de la Corderie, a place presumably associated with rope making. Not far away is Fossé aux Mats, perhaps a place for floating masts. The waters south of the Île d’Aix beyond the estuary of the Charente were a gathering area for naval vessels. The English navy, anxious to strike a blow at French naval power during the Seven Years’ War, conducted a lightning raid here in 1757. Aix was overrun in the space of five hours by a force of 17 ships, 65 transports, and 10 000 men. Evidently, the British had good maps too.

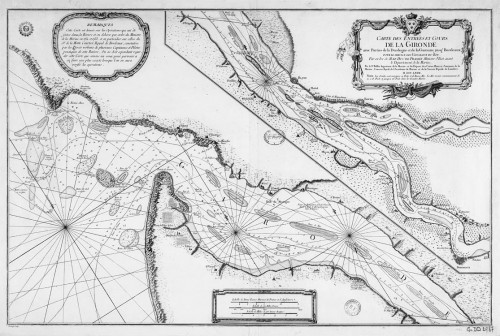

A lighthouse, the Tour de Cordouan, was constructed at the entrance to the Gironde to help guide ships on their way to Bordeaux. Another passe, or channel, lay to the north near the Pointe de Terre Nègre (the name suggests a connection to Africa, if not to African slaves). As ships made their way upriver, navigators had to avoid shallows and islands in the middle of the channel.

Vernet’s painting shows the bustle of loading and unloading activity along the banks of the Garonne River at Bordeaux in 1758. Large buildings flank the harbour area. They date from the early 18th century and demonstrate the degree to which this provincial city and hinterland was becoming rich from commerce, especially from the trade in sugar. The raw sugar was imported from the Antilles, refined in Bordeaux, and shipped out again to various European markets. For every urban trade, there was a rural complement of village craftspeople living off the manufacture and carriage of products and produce to and from Bordeaux. For example, potters in places like Sadirac, less than ten kilometres from the Garonne, made cone moulds used in the sugar refining process.

The Gironde estuary was a busy shipping artery. As many as 60 vessels at a time might seek shelter during inclement weather near l’Île de Blaye. Secured by a citadel, the port of Blaye, opposite the island of the same name, was a strategic position and communication hub. A postal route ran up to Paris via Poitiers from Blaye. Mail was exchanged with Bordeaux by boat along the Garonne-Gironde waterway. Blaye may have been a convenient place to put last-minute letters aboard ocean-going vessels before they put out to sea, a common practice for ships leaving inland French ports. The various waterways supported by a system of post roads helped move letters, dispatches and reports originating in the counting houses of French merchants or in the colonial offices (bureaux des colonies) of the French Minister of Marine toward the Atlantic and New France. The system worked largely outside the purview of the royal postal authority.

Getting Mail across the Ocean

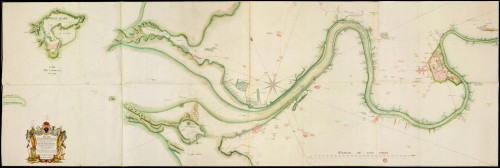

Map of the Gironde Mouth and Course with parts of the Dordogne and the Garonne up to Bordeaux…, 1767, by J.-N. Bellin

There was no formal postal system for maritime mail, but because of the increased flow of mail, there was a need to organize mail handling more efficiently. The merchants of Québec had complained that unscrupulous persons were meeting the boats before everyone else and ferreting through mail that was not theirs. So, in 1732, the Intendant of New France ordered the captains of incoming vessels to wait until they disembarked at Québec before handing over the mail. Across the ocean during the 1740s, the chambers of commerce of the principal ports—La Rochelle and Bordeaux—involved in the Canada trade assigned a specific gathering point for the dispatch and reception of colonial mails.

Gulf of Saint. Lawrence, showing the Island of Newfoundland, Straight of Belle Isle, Ile Royale (Cape Breton Island) and a portion of Acadia

Winter posed a daunting challenge to navigation between Canada and France. For six months of the year, the St. Lawrence River was closed to navigation, owing to ice and snow, which could damage a ship’s rigging and hull. The window for corresponding was short. In the second half of the 17th century, the first ships arrived from France in July or August. The later the arrival, the shorter the correspondence season, and no one wished to write a letter before first taking stock of the contents of letters received from France, although on occasion they might have to. In 1745, during the War of Austrian Succession, the mails for Canada never arrived. Tired of waiting, the colonists took a stab in the dark and dispatched their letters aboard ships destined for France and the Caribbean. The response to the year’s inbound letters would have to wait.

The ships had to depart by late October. Government personnel were given leave to catch up with their correspondence. Merchants barely had time to exchange their incoming merchandise for outgoing commodities. All the while they were busily preparing balance sheets, orders, and business advice. The French commercial correspondent, like today’s blackberry addict, had an insatiable appetite for news. Mail was the only way to learn of the safe arrival of cargo overseas, and it allowed merchants to follow economic trends and arrange to ship one commodity in place of another.

In February 1756, Abraham Gradis, a merchant of Bordeaux sent out two vessels, La Renommée and Le Robuste. They were to travel to Québec in the spring and then sail for Saint-Domingue with a cargo of fish (cod, salmon, eel) and wood planks. Presumably, the cargo was to be exchanged for raw sugar destined for Bordeaux. Within a month Gradis had changed his mind because of a fortuitous royal decision. Now the ships were to take on furs at Québec and then head straight for La Rochelle. Instructions were sent to each of the captains and F. Bigot, Gradis’s partner in Québec, on March 24. The following month Gradis changed his mind again. Now both captains were to travel to Saint-Domingue and thence to France. In the same year, the captain of Le Robuste was instructed to change plans on seven occasions in letters dated April 9, 11, 28, May 1, 13, and 23, and in June. In the last message, the captain was encouraged to exercise his judgement, although parties in Saint-Domingue had been advised to expect the ship from Québec:

Nous vous confirmons ce que nous vous avons ordonné dans les autres lettres de vous charger en morue, feuillard, planches et barriques d’huile de poisson et d’aller à Saint-Domingue, à moins que vous n’ayez trouvé un frêt intéressant en pelleterie et castor pour La Rochelle qui puisse nous rapporter entre 70 et 80,000 livres. Messieurs Batanchon et Marrot au Cap vous donnerons les ordres que nous leur avons envoyé.

Gradis was confident that the captains would obey his instructions and that his letters would get through. He wrote to each of them early in August, having received letters from both of them: on June 20 and 23 in the case of one, and on April 23 and June 16 in the case of the other. He received confirmation that at least one of the ships would sail to Saint-Domingue by mid-September 1756.

Throughout, Gradis was operating under the assumption that there would be a continued flow of ships across the ocean. Alternatively, he could reasonably expect his ships, in crossing paths with others, to exchange news in the Gulf of St. Lawrence or at Louisbourg. He could afford to change his mind several times within one business season and cast his line over a distance of thousands of kilometres. The British navy notwithstanding, Gradis was accustomed to a level of transatlantic service that was efficient and flexible, and he took advantage of every opportunity available to speed letters on their way.

So too did Hachard de Saint-Stanislas, an Ursuline nun who, early in the 18th century, exchanged mail with her father in Rouen from her new home in New Orleans. Hachard tied the expedition of her dispatches to the shipping schedule. Over time, the French learned to steer clear of the late summer hurricanes that routinely pounded the Gulf coast. When a ship pulled into port with a cargo of African slaves, Hachard made sure that her mail was put aboard for the return voyage to France. Her letter of April 24, 1728, was delivered to a vessel whose departure was delayed, so Hachard fetched the letter and transferred it to another ship, penning a post script at the bottom, “et cejourd’hui 8 May 1728 apprenant qu’il y a un prêt à metre à la Voille je l’acheve (la lettre) présentement….” The timely departure of mail was important to this Lousianaise.

Facilitators of Mail

Human initiative and oversight was crucial to transatlantic mail. Networks of informal mail agents emerged in the ports of France and New France. French correspondents trusted their outgoing colonial mail to these agents who were expected to put their letters aboard vessels working the Canada trade. Many agents were directly connected to the shipping business. Indeed, were it not for the merchant marine, there could have been no effective mail delivery across the Atlantic.

The Gradis company in Bordeaux handled the mail for a range of colonial notables, among them the King’s Surgeon, the Governor of New France (Vaudreuil), Montcalm (General of the French armies in North America), the Bishop of Québec, and François Bigot, the Intendant of New France.

Gradis looked after the Intendant’s personal affairs, purchasing property and wine on his behalf, watching over his wayward and indebted brother, and forwarding family mail. The largesse extended to Bigot’s mistress, Mme de Péan. On one occasion, Gradis sent his wife with her to buy clothes for Bigot’s niece. “Madame Péan et Madame Gradis ont fait de grandes libéralités de votre bourse.” Gradis had the full, if long-distance, confidence of Bigot, which was not surprising since they were in business together in the commercial firm known as la Société du Canada. Gradis was indispensable to Bigot for he was on intimate terms with the Duc de Choiseul, the royal official in charge of the colonies.

Having a mail agent on either side of the Atlantic was one means of ensuring that your letters got through. Given the vagaries of marine transport, other steps were taken to minimize the danger of a letter going astray. Correspondents sent multiple copies of the same letter on different ships. They sent mail via routes in which they had confidence. Upon learning that a route was more dangerous, they would simply stop using it. To make it easier for their counterparts in France to discover whether a rupture in the flow of letters had occurred and to minimize the inconvenience, they would summarize the contents of a previous letter. To borrow a term from modern parlance, this was an exercise in risk management. Correspondents had to make do with les moyens du bord, because it was the only way to do business. Delay was taken in stride.

Continental Perspective (show)

The transatlantic postal connection consisted of informal networks operating in tandem with maritime commerce in the face of uncertain climate conditions. The transmission of written information over long distances was the main focus. A brief look at the continental perspective suggests a system made up of interlocking overland and waterway segments. Once the message or the messengers step ashore in the principal French ports of North America, a new set of rules dictated the flow of communication and authority. Some of the routes by which information travelled lay beyond normal channels of communication due to the unofficial nature of the transactions.

The East Door

Louisbourg, a threshold between the Atlantic and the Gulf of St. Lawrence, was an important link in the continental chain of command. It was an emporium of commerce and an outer rampart of defence, and attracted New England traders as well as French ones. The practice of trading outside the French empire caught some unawares. In October 1727, Alexandre Cottrell, Captain of Le Prudent from Saint-Malo, encountered an English ship at Louisbourg. Endowed with a commission de guerre, he captured the vessel. Subsequently, the Governor of Île Royale threw the captain and crew in jail. Cottrell had broken a cardinal, if unwritten, rule of Louisbourg commerce: Business with les anglais was not to be interfered with.

Louisbourg was a vital port of call for the Canadian and Caribbean economies. Ships carried produce from Québec that was marketed through Louisbourg to the rest of the Atlantic world. The distance between Québec and Louisbourg being much shorter than between Québec and Martinique or Bordeaux, Canadian ships could operate up and down the St. Lawrence later or earlier in the year than their French counterparts sailing the St. Lawrence. Larger French ships moved regularly between Québec, Louisbourg, the Antilles, and the coast of France. In 1755, Gradis’s La Renommée travelled from France to Québec, arriving on May 23. It sailed for Louisbourg with a cargo and returned to Québec a second time, whence it was expected to leave for its return voyage before the year was out.

French correspondents could safely assume that mail sent via Louisbourg between late April and September would be sent on to Québec aboard a French or Canadian vessel. A ship leaving the coast of France in spring (April) or late summer (September) would arrive 50 days later in Louisbourg, on June 19 or October 20, respectively. In the former case, this left plenty of time to meet up with vessels about to depart for Québec. Similarly, mail could leave Québec on board a Louisbourg-bound vessel throughout the fall. The Chevalier de Lévis reported that he had just received mail from Louisbourg and would, by return trip of the same vessel, answer his French correspondent. He was determined not to convey too much sensitive information, “comme ma lettre court les hazards de la mer,” but sharing some news was probably better than sharing none.

Overland from Louisbourg to Québec

If mail arrived after the closing of the St. Lawrence, it might travel overland. Bougainville from Québec writes on April 19, 1757: “Ce soir on a eu par la voie de Louisbourg des nouvelles de France en date du 28 8bre [octobre]. Le bâtiment était parti de La Rochelle le 6 9bre [novembre] et arrivé à l’Isle Royale le 30 janvier.” The courier left Louisbourg for Québec on February 3.

The return itinerary was also practised. Québec correspondents would send their letters overland to Louisbourg so they could be put aboard the first ships to leave for France in spring. Writing from Montréal in 1758, Montcalm lamented: “… écrire voilà mon occupation.” The Louisbourg courier was to leave on the morrow.

Authorities in Louisbourg hired Micmacs from Miramichi to carry dispatches up the Saint John River to Québec. The service dates from the turn of the 17th century, when travelling Aboriginals carried dispatches between mainland Acadia (Port Royal, Pentagouet) and Québec. It still existed in June 1749, when provisions were sent to Lake Témiscouata to assist couriers carrying messages between the two colonies. It is likely that many of the messengers were themselves Aboriginals. This is hardly surprising considering that their villages were to be found along the portage route. James Peachey, British engineer with the 60th regiment, came across a village at the junction of the Saint John and Madawaska Rivers in 1784. Although he was not impressed with what he saw—“the Indians have made no improvement here but live entirely on Moose Meat and fish”—it is likely that the village existed during the French régime. These locations on either side of the St. Lawrence and Atlantic divide were known to Aboriginals and Europeans.

While travelling down the Kennebec in 1773, another route to the East coast, Hugh Finlay came across an abandoned Abenaki village (Aransoak) located downstream from a rapid, deserted some two decades earlier. He was guided by a crew of Aboriginals familiar with the route and the Abenaki language. As they knew where they were going, they were superbly qualified to carry Englishmen and messages hither and thither.

The Legs of the News

Aboriginal messengers were often the legs of the news in New France, although Frenchmen, Canadians and Métis (many of whom were voyageurs) moved information as well. News followed the Aboriginals around in the dispatches they delivered and in their observations made en route. Two Québec merchants wrote in January 1746: “… il est arrivé hier des sauvages, venant de l’acadie qui raporte des lettre des Missionaires et un Journal de M. Roma qui est à Isle Saint-Jean.” The “sauvages” brought the news that there was a scarcity of foodstuffs and wood at Louisbourg, then under occupation by British troops. Many were dying, they reported. Hearsay made the long voyage along with the written letters.

On July 31, 1730, news of the birth of an heir to the throne officially reached Québec from France. Unofficially, word arrived via a travelling band of Abenakis just up from New England, in April. As the final showdown with the British loomed, the French continued to use Aboriginal messengers. Their dispatch allowed for the fluid exchange of news between Canada and the Ohio theatre of conflict: In the dead of the winter in 1755, it took 39 days for a courier to travel between Fort Duquesne (Pittsburg) and Montréal. Aboriginals could also be relied upon to intercept enemy communication. Late in August 1759, when Québec was about to fall, the Abenaki captured a small expedition of seven Aboriginals and two British officers and brought them to Québec. Two metal chests containing letters addressed to officers serving in Wolfe’s expedition were intercepted. It is possible that the documents contained little sensitive information, as secret instructions would have been issued verbally to the officers in order to ensure confidentiality.

Illicit Commerce and Communication

Aboriginals were trusted messengers, message interceptors and smugglers. The Mohawks of Kahnawake were active in the contraband trade between Montréal and New York. They served as conduits of merchandise, furs and mail. References to the trade in contraband French furs in exchange for English merchandise occur throughout the late 17th and 18th centuries. By 1709, Governor and Intendant confess their impotence vis-à-vis the illegal trade to the Minister of Marine: “Ce commerce est péjudiciable au Royaume, mais il n’est pas possible de l’empescher par la force, il seroit mesme dengereux de l’entreprendre par le grand interest que nous avons de menager les Sauvages.”

A portion of the active population of Kahnawake lived off this activity by serving as couriers or by outfitting smugglers. Two French smugglers—the Desauniers sisters—operated quite openly out of the Mohawk village. A key factor in the pervasiveness of smuggling was the prevalence of corruption at all levels of the administration, notably in Québec, where Bigot and La Friponne held court.

Within New France, there was a steady market for English manufactured goods. A search of 506 locations in Montréal in 1741 found that 449 (89 per cent) had English goods. Among the culprits were parish churches and convents. The spirit of evasion was widespread. As indicated above, trade with the English was regularly practised in Louisbourg, and smuggling with English and Spanish colonies was a staple of life in New Orleans. Canada was not remarkable in this respect.

There can be no smuggling in the absence of efficient, if subterranean, means of transport and communication. The information system was based on confidentiality, discretion and ease of transport. The canoe, a ubiquitous form of transport, was ideal for use in shallow and swift waters and was easy to portage, and thus was favoured both by smugglers and the authorities who pursued them. The mere ownership of a birchbark canoe was enough to draw the attention of officials, who, in 1723, enacted an ordinance that made registration of these craft mandatory. Efforts to contain smuggling were not successful, and a generation later the trade was still active.

Robert Saunders was a prominent merchant of Albany, New York. A justice in the county court of common pleas, he became town mayor in 1750. Active on the English side of the smuggling racket, he employed five or six Aboriginal couriers, whose job it was to carry the French furs southward and the English merchandise northwards, as well as the related paperwork heading in either direction. Saunders kept a letterbook in which he transcribed copies of his outgoing correspondence. His French partners were sticklers for secrecy, so Saunders addressed them in code using symbols such as a pipe-smoking chicken or Roman numerals, e.g., Monsieur III.

As the following excerpts demonstrate, Saunders was fluent in French, commerce oblige:

“Monsieur. Il y a autour de 10 jours que je vous ay Ecrit et envoyer un Baril de bonne huitres par un sauvage qu’on appelle Marie Magdelaine …” (October 19, 1752)

“Monsieur, Je vous ai Ecrit et Envoye payment pour 50 (livres) de castor par Tiogaira, porteur de ces 50 l(ivres) de castor … je vous envoie Presentement par la porteur de la presente Sauvagesse Marie Magdelaine elle a un impediment à un de ces deux yeux(?) … elle me dit qu’elle vous connaît bien …” (July 5, 1753)

“Monsieur et Amis, J’ay recu le votre en date du 29 juin par la Porteur de la présente Canaguoise avec quatre Paquet (de fourrures) pesant deux cent et dix livres.” (July 24, 1753)

Saunders served as a postal lifeline for his anonymous partners, forwarding news and newspapers from Europe. The underground postal network extended as far as Québec. On May 5, 1753, he told one Montréal merchant: “Je n’ay pas recu de Lettres pour vous de france Encore mais pour un Monsieur a Quebec Jay receu deux que J’Envoye par le porteur.” On October 9, 1754, he dispatched another letter to a Montréal correspondent: “Inclos vous avez une lettre receu sous mon Couvre pour messieurs Delanneur et gautier negotians a quebec que je vous pris de leur en faire tenir.”

One wonders how these secret letters travelled between Québec and Montréal. Perhaps they were carried by a messenger service?

St. Lawrence Valley: An Extended Village (show)

“It could really be called a village,” Pehr Kalm wrote in describing the St. Lawrence Valley in 1749, “beginning at Montreal and ending at Quebec … for the farm houses are never above five arpents and sometimes but three asunder, a few places excepted.”

By definition, a village, even an extended village, is a place where news spreads swiftly. The scale of life is such that whatever happens becomes news that makes the rounds by word of mouth, by letter or both.

Social networks were set in place during the late 17th to early 18th centuries, enabling the circulation of news. It was no accident that developments easing the flow of communication matched the advent of a market in wheat and other grains. The St. Lawrence Valley was coming together as a recognizable, cohesive and integrated geographic unit.

The process took time. In the mid-17th century, correspondents wrote home to far away France. During the following century, home got closer and there was more reason to contact someone living in a town or côte along the St. Lawrence. Systematic settlement made it easier for the Canadians of the St. Lawrence Valley to convey oral messages over an increasingly wider distance.

Consider the situation in the second half of the 17th century when a string of miraculous cures established the reputation of the church of Sainte-Anne-du-Petit-Cap (Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré). Those cured were from the actual parish or places nearby: Chateau Richer in a 1662 case, Québec in 1664, and Saint-Laurent-de-l’Île d’Orléans in 1701. Groups of devoted pilgrims came to Sainte-Anne from next-door Chateau Richer and Sillery (just upstream from Québec) during the 1670s and 1680s. Notables in Québec, less than 30 kilometres away, heard of the miracles occurring in Sainte-Anne. In all of these late 17th-century examples, the news of miracles made the rounds but essentially within a limited geographic extent. As the rest of the St. Lawrence Valley was progressively colonized in the early 18th century, with sons and daughters moving away from the family homestead but never completely out of touch, so was the internal frontier of verbal news expanded. For example, in 1759, it would have been next to impossible for habitants not to have heard about the arrival of the English.

Communication at the regional and local scale was caught up in two types of social activity. First, letters were prepared and exchanged with a view to conveying a message between two parties unable to have a conversation in person. The priority was transmission. Second, communication was a public experience, a ceremony, and an informal exchange between families and neighbours. In this second instance of unwritten communication, the medium helped frame the manner in which the news was conveyed and ultimately the contents of the message. The emphasis is on representation of shared beliefs and the emotional runoff contingent upon person-to-person exchanges.

Transportation and Transmission: Water

In season, the St. Lawrence River was a liquid information highway frequented by dozens of boats and schooners. During the early 19th century, 200 navigators resided in Québec. They were the masters of vessels and boats sailing between Montréal, Trois-Rivières, Québec, and Louisbourg. Along the St. Lawrence, craftsmen specialized in building boats and ships near the royal naval yards in Québec and elsewhere.

In 1705, Guillaume Levitre of Saint-Pierre-l’Île d’Orléans, agreed to build a vessel for Messieurs Martin and Jeanne of Québec. The work was to be done at l’Île Dupas near the mouth of the Richelieu River. As l’Île Dupas was 175 kilometres upstream from Québec, the agreement speaks to the emerging economic web along the St. Lawrence River.

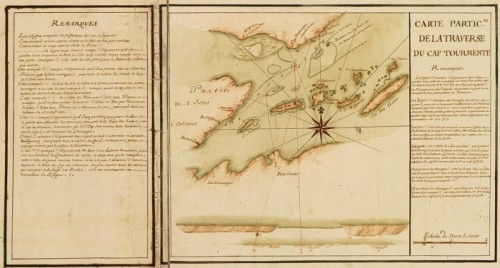

River transport ensured a steady flow of information, but navigators needed to know where they were going. Mapmakers charted the trickier portions of the river downstream from Québec. Bays and inlets were set aside as anchorage havens, among them Cap-aux-Oies, Baie Saint-Paul, La Malbaye, Le Bic. The French favoured the north shore route upstream from l’Île-Verte for it was easier to navigate into the prevailing north-west wind, hence the details in Des Hayes’s map (ca. 1685) regarding this side of the river, for example, the good anchorage space 11 fathoms from the shore at Cap-aux-Oies or the sandy beach at Port-au-Persil where boats could be drawn up. Along the St. Lawrence, Canadians adopted the habit of going out to meet the ships as they passed by to supply or sell refreshments. In exchange for the food and water hoisted up, news from overseas, or upriver Québec, trickled down.

Particular Map of traverse of Cap Tourmente (detail), 1733, by J.-N. Bellin and H. des Herbiers de Lestanduère

In addition to the tall ships, various types of smaller vessels moved people and information. Birchbark canoes and wooden dugouts were almost everywhere. The Crown built flat-bottomed boats and wooden dugouts to ferry troops around. Housed in sheds, these bateaux were valuable assets. A 1717 ordinance called attention to the theft of the King’s boats, which were being dismantled and sold for boards and nails. Royal boats carried messages and people. In 1733, colonial authorities created the position of patron de chaloupe to carry dispatches for the Governor and the Intendant along the St. Lawrence. Kalm, en route to Montréal in the governor’s boat in 1749, mentions the halt at Trois-Rivières, “… where we stayed no longer than was necessary to deliver the letters which we had brought with us from Québec.” He was likely travelling with the patron de chaloupe.

Le chemin de Roy or The King’s Road

During the 1690s, royal messengers began carrying dispatches on land. They may have taken private mail as well. It was customary for persons to give their letters to travellers who willingly carried them as a favour. This custom informed the expectations of letter writers. Father Naud of Kahnawake was upset that his mail from France had not been sent on ahead to the mission when it arrived at Québec, so confident was he that he could subsequently find an occasion to send the reply back for dispatch to France. Some of Naud’s mail could have travelled on land by cart in summer or by sleigh in winter.

Road construction in New France was a local affair. Roads might be built in the direction of the seigneurial mill or the parish church, in order to accommodate short-distance travel needs. The official in charge of road construction in New France (Grand Voyer or Chief Surveyor) found it was not always easy to persuade habitants to fulfill their road building and maintenance obligations. On occasion, the Intendant might pass an ordinance to enforce the plans for a road. An inspection of the l’Île d’Orleans in summer 1731 by Grand Voyer Boisclerc revealed that roads and bridges were in considerable disrepair. In the parish of Sainte-Famille alone, 46 bridges needed fixing while the road in the parish of Saint-Jean had been washed away by high tides. As yet, there was no road around the circumference of the island. This task was accomplished in the course of the next three decades, i.e., by the 1760s. The experience with the reluctant habitants of the l’Île d’Orleans fresh in his mind, Boisclerc undertook the more ambitious if foolhardy project of building a road between Québec and Montréal, an undertaking in which he was ultimately successful.

The chemin du Roy or King’s Highway between Québec and Montréal was completed in 1737. Ditched on both sides and 24 feet (7.3 metres) wide, it allowed for the flow of passengers, post and messengers. For the inhabitants charged with construction and upkeep, the road was a trade-off. On the one hand, it removed chunks of tillable land from farm use. On the other, it linked the rural communities in a single interlocking chain, reinforcing the pattern of the extended village. Although not officially a post road, the chemin du Roy was used to move mail. On Christmas Day, 1748, Élisabeth Bégon gaily wrote from her Montréal residence: “Pour faire quelques compliments du 1e de l’an, on m’a dit qu’il partait un courier ces fêtes.” The courier was likely headed for Québec along the chemin du Roy. Were he to have left the next day, he would have faced a blizzard of blowing snow that reached three to four feet (a metre) in height, “jusqu’au ventre des chevaux.”

Winter did not prevent travel or the exchange of mail along the main road of the St. Lawrence Valley. Governor and Intendant with their respective entourages moved from Québec to Montréal in midwinter. Here they could better administer the fur posts in the upper country and attend to the subjects of the King who lived in the district of Montréal. A description of one trip in 1753 shows that there were established relay stations where teams of fresh horses were kept. Drivers familiar with the best routes, which sometimes lay out across the frozen surface of the St. Lawrence River, were available for hire. Inhabitants of the parishes along the road were instructed to pack down the snow before the cortege came through. Snow packing was possibly one more royal task for inhabitants, as according to the terms of a 1726 ordinance, they were required to mark out winter roads by planting branches in the snow. In the end, making travel easier for the lordships made it easier for them to move around too.

Two things are clear: By the 1750s, intracolonial road travel was a reality, and mail was moving regularly between Québec and Montréal. Correspondents wrote each other on appointed days of the week. (Harrison, 1997: 78) Montcalm explained to his second in command, Lévis, newly arrived in the colony and stationed at Québec, that they could keep in touch by courier extraordinaire or by regular mail: “… il part tous les lundis au soir un courier,” for Montréal. A year later he was disappointed that, for some time, “ il n’est arrivé ni courier de Québec ni lettres.” The Marquis, then in Montréal, had come to rely upon the service.

Montcalm was not the only one depending upon the mails. The circulation of letters tied the elite of the colony together, for, other than in person, there was no better way to conduct business, trade favours or cultivate alliances.

Correspondence allowed families dispersed in space to coordinate their efforts. Cousins, in-laws, and blood relatives might run the partnership’s Québec office or oversee its interest in the Upper Country, informed by a constant stream of written instructions. The mail tied the whole enterprise together like one long ribbon of words. Moreover, business was not the sole object of the exchange. A personal element of equal import could burrow its way into the correspondence. The personal touch was purposeful, in as much as the exchange of favours and courtesies and the arranging of marriages facilitated class solidarity and reproduction.

Talk, Letters, Ceremony

There is no denying the social usefulness of writing. Yet, as a means of communication, it did not function in a vacuum. An outstanding feature of life along the St. Lawrence River was the ubiquity of talk and the customs and pomp and circumstance surrounding it. Voice came truly into its own at this scale of social relationship. Everyone participated. The powerful bourgeois-gentilhommes clustered in one or other of the colony’s towns. No doubt they dined together and talked out the issues of the day (while they played cards) as did their counterparts in tidewater Virginia. The ordinary folk gathered within their rural parish constituency. In town as in country, rumour and ritual were the preeminent media of communication.

“Les bruits qui courent,” were a daily staple of communication in the colonial capital of Québec in times of peace and war. A young woman from l’Île d’Orléans arrived in town in 1696 bearing tidings of an imminent invasion of enemy ships from New England. While the woman went to the Chateau to tell the Governor her story, the boatman who had brought her to town spread the word that the English were coming: “… rapidement toute la ville fut en émoi.” The woman was eventually thrown in jail when the hoax was uncovered—her lover had invented the story—and she was accused of spreading false news in a manner harmful to the interests of the Crown.

Talk could be manipulated like a barbed instrument. Rumour and a solid belief in a conspiracy theory made town dwellers in Québec resentful over the unethical practices of merchants speculating in foodstuffs. Talk was a popular means of injure among the elite. Opposed to the theatre on moral grounds, in 1694, Bishop Saint-Vallier of Québec offered Governor Frontenac 100 pistoles if he agreed not to put on a performance of Molière’s Tartuffe at the Chateau Saint Louis. Frontenac agreed to take the money but then spread gossip about the affair, an initiative that amused the gallery, but undoubtedly undermined the Bishop’s moral authority.

Rumour was rampant in Montréal where, in 1731, a group of citizens testified in court that their neighbour, Mère Guignolet, maintained a house where vice of every description was committed. The Guignolets used foul language: “Crême et baptême, Vous êtes une conquine et une putain.” Evidently the witnesses were not deaf. Like their counterparts in colonial New England they were always eager to eavesdrop; they had good memories, and they repeated to one another, or in court, what they heard.

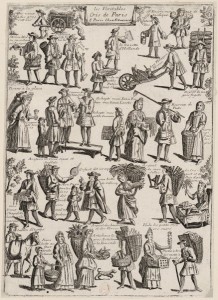

(Figure 22)

Talk spread throughout the colony borne by travelling sailors, voyageurs and Aboriginals hired to carry dispatches. It entered and exited letters. In 1746, in the correspondence of Messieurs Havy & Lefebvre of Québec, a letter tells M. Guy, their Montréal correspondent: “…voilà tou ce que j’ai entendu au Chateau ayant oui lire les lettres et lue.” They report what they have read and heard while visiting the Governor’s palace, and Guy, upon learning the news could repeat it to his entourage and thereby all of Montréal.

In New France, taverns were a favourite forum for popular talk. Games were played, deals were struck, schemes devised. Taverns were a fun place to be, not least because there was so much singing. Melodies sung by choirs of voyageurs travelling the waterways of the Upper Country, chanties sung by sailors out on the ocean, traditional tunes of peasant farmers; all could be taken up with a multitude of variations au cabaret. Small wonder that the drinking establishments of Louisbourg stayed open well after the official closing time. In Martinique, despite the official interdict, the town of Saint-Pierre boasted 200 taverns. The search for conviviality, not just rum, fuelled the demand for these establishments.

Pointed Exchanges

Voice was intrinsic to social life in New France, but it could get its protagonists in trouble. Forty-four per cent of individuals brought before the Royal Courts of Canada were accused of verbal or physical violence. The onset of the former led almost automatically to the latter. Words were used to taunt and sometimes provoke one’s adversaries.

A few popular examples of this: Antoine Dufaut made unflattering remarks to a group of friends and neighbours, who were out bowling near the ramparts of Montréal on a Sunday evening in July 1736. One member of the group took exception to these comments. He began by insulting Dufaut, and eventually a fight broke out. On another occasion in 1733, family and friends gathered outside the Montréal home of Charles Viger, a carpenter. Viger was verbally accosted by the two Brossard brothers, who were upset over something that a member of the Viger party had said. The incident escalated into fisticuffs before the protagonists could be separated.

An extreme example involved a quarrel between two officers over a game of billiards, which came to a dramatic end: “Je m’en foutre de la partie,” said one. “Que dites vous,” exclaimed the other. The climax of the confrontation was a sword fight in which one of the protagonists was stabbed. He eventually died of his wounds.

In this as in all human affairs, one thing leads to another. Yet among the people of New France, gens ordinaires and members of the elite, the deeply ingrained sense of honour was such that people said and did the darndest things.

Swearing and Blasphemy

Since the 19th century, French-Canadians have built up a repertoire of swear words that takes its cue from Catholic liturgy and ceremony. The repertoire of their 18th-century ancestors inhabiting New France was different.

In Louisiana, the judicial archives suggest that such words as foutre, coquin, bougre, and fripon (cheap) were among the favourites. Generally speaking, swearing in New France reflected the value assigned to the sense of honour of men and women. If you wished to insult a man you would call into question his honesty using such terms as fripon, voleur, geux, or cartouche. Women were reviled for their extramarital sexual activity as in putain (whore), and its various synonyms, marcrelle, garce, coureuses de garcons. Although on the surface, putain might seem to be less potent than its Italian equivalent of putanissima, the term could be effectively used in conjunction with others, as in bougre de garce. The wife of an army officer was superlatively reproached in 1728 for being “plus putain qu’une cavale,” a cavale being a mare whose primary purpose was to produce other horses.

The Importance of Showing Off

In the ancien régime, social behaviour was necessarily a theatrical production for it was linked to the pursuit of status practised at all levels of society. In New France, as in early modern Italy, which, according to Peter Burke, is the quintessential example of theatre society, it was imperative for individuals to fare bella figura. No one wished to lose face or sacrifice honour. The same could be said of social groups and classes. An elite group could create a splash with its splendid houses, carriages, and dress. The response of the crowd of ordinary people might come in its mischievous behavior and talk at the tavern, on market days, or at festivals, or even in its choice of a particular manner of dress. In the ongoing game of tit for tat, peasant and noble reached for a variety of symbols with which to communicate their identity, if not their authority.

Power in New France was a staged production. The proclamation of official ordonnances required pomp and ceremony. They were proclaimed and prominently posted in New Orleans, as in Québec, to the accompaniment of drummers and a town crier, with soldiers and officials standing alongside, for effect. In rural communities, ordonnances were read out by the militia captains prior to posting them on the church doors. A balder demonstration of power would see the master of a Louisiana plantation, whip in hand, punishing a slave in full view of his peers.

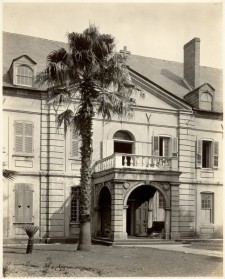

Power was staged, but there was competition among the “haves.” Johnston documented the 1720 royal battle between Governor Saint-Ovide of Louisbourg and Mézy, the commissaire-ordonnateur. Each official proclaimed his ascendancy over the Conseil Supérieur by means of a written public notice posted on the door to the parish church, the usual place for important public notices. Mézy’s notice was torn down within the hour; the Governor was in no mood to negotiate his authority. A similar tug of war pitted the Governor against Intendant Dupuy of New France in 1727. The Intendant, newly arrived from France, threatened to unsettle the Governor’s established way of doing things. The confrontation featured a posting of ordonnances and counter-ordinances emanating from the Governor’s Chateau and from the Intendant’s Palace. Ultimately the Governor was victorious; the King’s dispatches of September 1728 announced Dupuy’s dismissal.

Conflict over issues of rank and status took place out in the open. Bickering over protocol and prestige were bound to attract attention. Along the extended village of the St. Lawrence River, inside and outside city walls, they became the talk of the town.

Parish Constituency

Rank and dignity characterized all levels of society in Canada. They mattered to high-ranking officials, who demanded the right to bring their prie dieu to church, and to lesser officials such as the militia captain, who believed that it was his God-given right to occupy a particular pew in church. As community institutions, parishes in New France had a popular temper. In October 1714, the inhabitants of Côte Saint-Léonard on the island of Montréal balked at the prospect of being detached from the parish of Pointe-aux-Trembles. A man sent to transfer the blessed bread was intercepted. A bailiff sent to enforce order was threatened. The Bishop’s decision conflicted with an entrenched sense of community; the people of Saint-Léonard demonstrated their opposition.

The parish represents a local constituency, at times determined to defend its interests. Issues of status and local tradition play a large role in daily life. Face-to face encounters—verbal adresse and maladresse—count for a good deal at this scale of life. A grudge or a good word can go a long way, as can a raised eyebrow, a flutter of the lashes or a reddened face, all non-verbal gestures exchanged between potential lovers sitting near one another in church.

In contrast to the continental and the transoceanic scales, where the transmission purpose is paramount, communication at this smaller scale is something that is experienced personally or collectively within a primary group. The parish acknowledges its collective personality by attending divine service en bloc. The performance is scripted. One verse follows the next, according to the set ritual and liturgical calendar. The respective places of congregation and priest are fixed in a geography of ceremony: The priest in his robes speaks from up there, while we rise, kneel, sit, and repeat after him, down here. Something extraordinary happens inside the church: An ill or crippled person proclaims that he or she is miraculously cured, a couple decide to wed, à la gaumine, without the consent of their parents and priest. The event is experienced in full view of the assembly. They are the ones who will tell of what they saw that day. They are keepers of local tradition.

Outside the church, after mass, groups of parishioners assemble for a pipe or to socialize. All manner of business is transacted and words exchanged. Rumours are batted about like flies. There is a hesitation to head for home immediately as families and friends enjoy the pleasure of each other’s company. The church door is a natural place for the posting of written notices read out by royal officers or militia captains precisely because it was understood to be a popular place of assembly. Students of the siege and battle of Québec will recollect that it was on the door of the Beaumont Church that General James Wolfe affixed his notice to Canadians on June 30, 1759, enjoining them to maintain a neutral posture or face serious reprisals from the British. Wolfe’s was not a hollow warning!

The custom survived. As of 1825, a committee of the Legislature of Lower Canada argued that a local petition had to be posted on the church door for at least two months before it could be legitimately brought to the House’s attention. Six decades later, it was felt that the best way to reach those with a stake in the islands of Sorel—a law governing the use of the islands was about to be amended—was to put up a written notice on the church doors of the parishes concerned. Altnough lawmakers also proposed to place an ad in a Sorel newspaper, the continued relevance of the church door in 1884 is significant. Perched at the crossroads of communication—oral, ritual, clerical, secular, and royal—the church door would fulfill a key function in news transmission. It serves as a reminder of the complex and multilayered system of communication that moved messages and news back and forth and up and down the social network of the St. Lawrence.

Conclusion (show)

The French empire in North America would have been impossible but for the elaboration of written communication systems. The keeping of colonies required long-distance communication. The ability to correspond depended on the infrastructure of trading ships and corresponding merchants. Merchants and skippers, not the King’s men, were the backbone of news transmission across the Atlantic.

The ships carried news from Versailles and all manner of business paperwork. Religions institutions with branches in New France corresponded with their French head office. Scientists collected specimens, apothecaries swapped recipes. And a village woman from Normandy, barely able to cope with all the family affairs and lonely for her husband, in April 1731, wrote to her man who was working at a fishing station on Scatterie Island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Unbeknownst to her, he had been dead for four months. But she knew she could rely on a transatlantic network to carry her message far away.

In part, the transmission element defined continental communication. But circumstances and factors fashioned distinct purposes and patterns. Communication was the result of a gradual articulation between metropolitan society on the one hand and the créole and Aboriginal spheres on the other. The emerging colonial sphere was to some extent dedicated to the short-circuiting of imperial purpose through smuggling and other para-imperial activities.

The articulation process unfolded over three generations in Louisiana, resulting in a force called rogue colonialism. The initial impulse of settlement was imperial, but the balance of forces gradually shifted toward a colonial or créole centre of gravity. Over time, local officials, planters and merchants act according to their own interests. Messages are exchanged with France, but they also traverse the continent in accordance with or in contradistinction to the imperial connnection.

Outside the core zones of French settlement, Aboriginals were ambassadors of news. They carried dispatches through the Upper Country and eastern borderlands between New France and New England. The “middle ground,” which originally enveloped the Great Lakes and subsequently migrated West, was socially and geographically different from France, but, Havard reminds us, it remained a satellite of the metropole and its rogue colonial polities. The process of métissage or blending of native and European peoples, helped produce a a type of communication network as different from Europe as its counterparts in Africa, India, and South America. The news made it through, but something was modified, although not lost, in translation.

The extended village was the conduit of communication in the St. Lawrence Valley. For the colonials, the extended village—shaped and reshaped by its own vision and elbow grease—was home. Roads and river boats carried travellers and mail as regularly as the tides. Regularity of news conveyance together with the circumstances of propinquity made for a distinct social experience of communication. Oral and written information travelled each day, all year long. Theatrical performance accented the message. Neighbours talked outside the church, over the fence and along the St. Lawrence with the boatmen.

The intensity and multiplicity of communciation flowing through the regional network is striking. Compared to the transatlantic and continental settings, the interpersonal element in communication is more important. The conversation is not primarily about business or the King; it is not about the Aboriginals, nor is it beholden to their ability to bear witness. It is about the construction of a social world steeped in honour and based upon rank, solidarity, clientelism for the elite, the family farm, the society of côte and parish, and the ongoing interaction with other colonial spaces by the ordinary people.

L’art d’écrire, plate III from the Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, 1762-1772, by Diderot et d’Alembert

Communication at this scale is a piece with the ground floor of the socio-economy, as basic to exchange as a market place. (Braudel) It was a social glue of enduring character for, even after defeat in 1759, those remaining behind would carry on with the task of communicating, and making history: “Le gens de mon pays,” the song goes, “ce sont gens de parole.” The parole is a legacy of New France.

Suggested readings (show)

BANKS, Kenneth J., Chasing Empire across the Sea: Communications and the State in the French Atlantic, 1713-1763, Montréal, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002.

BÉGON, Élisabeth. Lettres au cher fils : correspondance d’Élisabeth Bégon avec son gendre (1748-1753). Établissement du texte, notes et avant-propos de Nicole Deschamps. Montréal, Boréal, 1994.

BRIGGS, Asa et Peter BURKE, A Social History of the Media, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2005 (seconde édition).

BROWN, Richard D., Knowledge is Power: The Diffusion of Information in Early America, 1700-1865, New York, Oxford University Press, 1989.

BURKE, Peter. Historical Anthropology of Early Modern Italy: Essays in Perception and Communication. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1987.

CHARTRAND, René. Canadian Military Heritage. Vol. 1, 1000–1754. Montréal, Art Global, 1993.

CHARTRAND, René, Monongahela, 1754-1755: Washington’s Defeat, Braddock’s Disaster, Oxford, Osprey Publishing, 2004.

CONROY, David W. Public Houses: Drink and the Revolution of Authority in Colonial Massachusetts. Chapel Hill (North Carolina), University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

DAWDY, Shannon Lee, Building the Devil’s Empire: French Colonial New Orleans, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2008.

DECHÊNE, Louise, Le partage des subsistances au Canada sous le régime français, Montréal, Boréal, 1994.

DONOVAN, Ken. « After Midnight We Danced until Daylight: Music, Song and Dance in Cape Breton, 1713–1758 », Acadiensis,vol. 32, no 1 (automne 2002), p. 3-28.

FRIESEN, Gerry, Citizens and Nation: An Essay on History, Communication and Canada, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2000, p. 81ff.

GADOURY, Lorraine, La famille dans son intimité : Échanges épistolaires au sein de l’élite canadienne du XVIIIe siècle, Cahiers du Québec, collection Histoire, Montréal, Hurtubise HMH, 1998.

HARRISON, Jane, Until Next Year: Letter-Writing and the Mails in the Canadas, 1640-1830, Gatineau et Waterloo, Musée canadien des civilisations et Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1997.

HAVARD, Gilles, Empire et Métissages : Indiens et Français dans le Pays d’en Haut, 1660-1715, Sillery, Septentrion, 2003.

HUBERT, Olivier, Sur la terre comme au ciel : La gestion des rites par l’église catholique au Québec, fin XVIIe début XIXe siècle, Québec, Presses de l’Université Laval, 2000.

JOHNSTON, A. J. B. The Summer of 1744: A Portrait of Life in 18th-century Louisbourg. Ottawa, Parcs Canada, 1983, réimpression 1991.

JOHNSTON, A. J. B., Control and Order in French Colonial Louisbourg, 1713-1758, East Lansing (Michigan), Michigan State University Press, 2001.

KAMENSKY, Jane. Governing the Tongue: The Politics of Speech in Early New England. New York, Oxford University Press, 1997.

LACHANCE, André. « Une étude de mentalité : les injures verbales au Canada au XVIIIe siècle (1712-1748) », Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, vol. 31, no 2 (septembre 1977), p. 229-238.

MATHIEU, Jacques, Le commerce entre la Nouvelle-France et les Antilles au XVIIIe siècle, Montréal, Fides, 1981.

MIQUELON, Dale, New France, 1701-1744: A Supplement to Europe, Toronto, McClelland and Stewart, 1987.

PODRUCHNY, Carolyn, Making the Voyageur World: Travelers and Traders in the North American Fur Trade,Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

MOOGK, Peter N. La Nouvelle France: The Making of French Canada — A Cultural History. East Lansing (Michigan), Michigan State University Press, 2000.

THOMPSON, E. P. Customs in Conflict: Studies in Traditional Popular Culture. New York, The New Press, 1991.

TRUDEL, Marcel, « Un déménagement annuel de la haute société en plein hiver, de Québec à Montréal » dans Mythes et réalités dans l’Histoire du Québec, tome 5, Cahiers du Québec, collection Histoire, Montréal, Hurtubise HMH, 2010, p. 57-66.

VERGÉ-FRANCESCHI, Michel, Chronique Maritime de la France d’Ancien Régime, collection Chronique Sedes, Paris, Éditions Sedes, 1998.

Original research: Dr. John Willis

Acknowledgment

I wish to thank the following for their research collaboration: Marguerite Sauriol, Jane Harrison, Nicole Castéran, René Chartrand. Lorraine Gadoury, Jean-Pierre Hardy, Christian Pederson, and the late Jean-Pierre Chrestien provided helpful comments on an earlier draft. Merci!