-

- Introduction

- Colonies and Empires

- The Explorers

- Jacques Cartier 1534-1542

- Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

- Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621

- Jean Nicollet 1634

- Jean de Quen 1647

- Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers 1654-1660

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson 1659-1660

- Nicolas Perrot 1665-1689

- René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

- Charles Albanel 1672

- Jacques Marquette 1673

- Louis Jolliet 1673-1694

- Louis Hennepin 1678-1680

- Daniel Greysolon Dulhut 1678-1679

- Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron Lahontan 1684-1689

- Pierre de Troyes 1686

- Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

- Antoine Laumet dit de Lamothe Cadillac 1694-1701

- Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye 1732-1739

- Economic Activities

- Population

- Daily Life

- Heritage

- Useful links

- Credits

Population

Religious Congregations

The missionary adventure in New France was remarkable. The travels, works and martyrdom of the members of religious orders who came to convert the “savages” have long fueled the popular imagination where the history of French North America is concerned. In this article by Claire Gourdeau on the religious congregations and their accomplishments, we discover, or rediscover, the various players in this adventure. The author presents all the congregations that sent missionaries to the colony and explains their reasons for doing so.

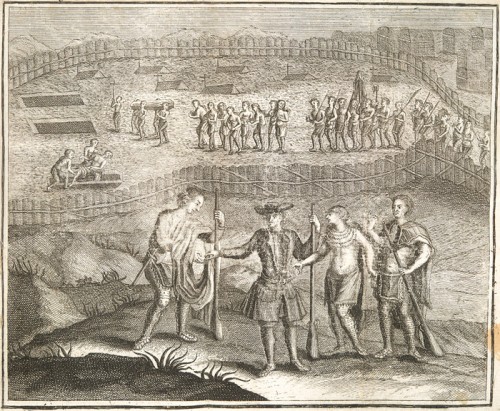

Recollects, Jesuits, Capuchins, Ursulines, Hospitallers — all were motivated by the same faith and aspired to one thing only: to convert Aboriginal people to save their souls. As she traces the history of this missionary work, which began with the arrival of the first Recollects in Quebec City, in 1615, Claire Gourdeau takes us on a journey through the continent and describes the pitfalls the missionaries encountered and the methods they used to reach their goal. The religious communities had meagre means, as they all depended entirely on the generosity of “benefactors” in France.

Despite their efforts, the missionaries never managed to bridge the immense cultural gap that separated them from the Aboriginal peoples. Having achieved only poor results, the religious congregations present in North America’s French colonies ended up devoting themselves to the education and support of the colonies’ populations of European origin.

Fighting the devil (show)

Bringing souls to God, throughout the world

From the 16th to 18th centuries, the French kings who administered the colonies of Canada, Acadia and Louisiana were mainly interested in the profits that this vast region could bring them. A colony was supposed to enrich the homeland with its natural resources. To this end, rulers concentrated on establishing companies to develop trade, troops to defend the territory and settlements to ensure that the colony survived.

However, the powerful Roman Catholic Church reminded the sovereigns that their duty towards God had priority over temporal matters. Nuns and priests from various religious congregations took their courage in hand and boarded the merchant ships to make the perilous voyage to New France, where they hoped to make Catholic converts among the numerous First Nations that had inhabited North America for thousands of years. The missionaries were convinced that they had to convert these poor souls whose ignorance of the “true God” would deny them eternal bliss in the afterlife.

The congregations had considerable experience in such undertakings. In the 16th century, the Counter-Reformation had awakened an impressive missionary zeal in France. In reaction to the wave of Protestantism sweeping across Europe, an unprecedented campaign was embarked upon to convert all the non-Catholics in the world. The first Augustinian, Franciscan, Jesuit and Dominican missionaries travelled throughout Africa, Asia and North America, establishing bishoprics wherever they went: in Haiti, West Indies, in 1513; in Goa, India, in 1534; in Manila, the Philippines, in 1579; and in San Salvador, Congo, in 1597.

New France, a promising territory?

Why were the missionaries so eager to save the souls of the New World’s inhabitants? No doubt because the Aboriginal populations did not know the Europeans’ Christian God and, unless they were baptized, had no chance of heavenly rewards after death. No one wondered whether they had their own beliefs. They had to be converted to Catholicism at all costs and made to abandon their pagan beliefs.Aboriginal peoples performed war dances, beat the drum to bring rain and asked shamans to interpret their dreams. Their belief system was based on animism—that is, they considered that every element of the natural world, whether tree, river, rock or creature, possessed a soul that should be respected. The bones of an animal that had been killed and eaten had to be treated in a certain way—for example, a beaver’s skeletal remains would be returned to the river—for, otherwise, the soul of the animal would tell the souls of its kind to escape the hunters’ arrows and traps, and this would lead to famine . In the summer of 1647, Marie de l’Incarnation wrote as follows on this subject to one of her religious companions in France:

The first Récollet missionaries

In 1615, four Récollets recruited by Samuel de Champlain in Paris landed at Québec. They were Fathers Denis Jamet, Jean Dolbeau, Joseph Le Caron and Pacifique DuPlessis. As soon as they arrived, they set off to establish missions in Huronia, in the Great Lakes region; among the Innu (Montagnais) at Tadoussac, on the North Shore of the St. Lawrence River; and among the Abenakis at Trois-Rivières. They were immediately confronted with the obstacle of language. How could they teach the concepts of God, the mystery of the Holy Trinity, the three theological virtues or the Virgin Birth in languages like Algonquin, Innu, Huron or Mohawk, which they knew nothing of and which were difficult to learn? In 1632, Gabriel Sagard, a learned Récollet father at the Huron mission, wrote:

The “truchements”

To solve their communication problem, the missionaries recruited young men from humble backgrounds in France. Such young men, including Pierre Boucher and Nicolas Marsolet, were poor but adventurous, brave, curious and eager to travel. Above all, they were extremely resourceful and were able to grasp the linguistic patterns of the indigenous languages, making themselves understood through gestures and miming. These interpreters, who were known as “truchements” (or, literally, helpers), were supported financially by the missionaries, who also provided them with an education they could not have obtained otherwise. If they returned alive from their dangerous mission after several years in the service of the missionaries, they might well rise in society. Pierre Boucher, for example, became governor of Trois-Rivières and founded Boucherville, while Nicolas Marsolet was granted a seigneury.

Despite their limited financial means and their small number, the Récollets carried out remarkable evangelization work. In 1618, Father Le Caron wrote the following passage about the education he was offering Aboriginals: “I have shown the alphabet to some of them, who are beginning to read and write quite well. This is how I have been busy, maintaining an open school in our house at Tadoussac.”

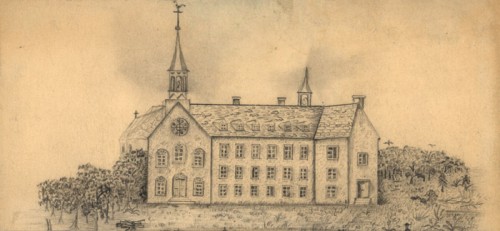

Pacifique DuPlessis had been an apothecary in France before entering the Récollet order. In 1617, he was sent to Trois-Rivères, where he devoted himself to evangelizing Aboriginal communities, educating children and caring for the sick, thus putting his previous training to good use. He is considered to be the first schoolmaster in New France. In 1620, the Récollets built the Notre-Dame-des-Anges convent, their first Canadian convent and seminary, in Québec’s Lower Town, where the Hôpital Général now stands.

In 1623, Father Nicolas Viel travelled to Huronia with other Récollet missionaries to help Father Le Caron with his work. One of these men, Gabriel Sagard, later published Le grand voyage au Pays des Hurons (1632) and Histoire du Canada (1636), in which, without overt prejudice, he described the Hurons’ everyday life, customs and habits, as well as the riches of the places he visited in this land, with its abundance and variety of flora and fauna.

Jesuit reinforcements arrive in 1625

Founded by Ignatius of Loyola, the Company of Jesus, also known as the Order of Jesuits, was a magnet for austere learned men. It rapidly became a powerful force, with its members occupying strategic positions in the royal courts of Catholic Europe. Jesuits were not only the spiritual advisors and confessors of kings and queens, but also their political advisors. They were known as skilful rhetoricians, excellent teachers and seasoned missionaries. Their missionary experience was indeed impressive: they went to India in 1541, Japan in 1549, the Spanish colony of Florida in 1565 and South America before the end of the 16th century.

In 1599, the Order published a pedagogical guide, Ratio Studiorum, that was avant-garde for its time in as much as it recommended that teachers adapt their teaching methods to various clientele, as well as to the demands of time and space in the places to which they were sent . In contrast to mendicant orders like the Récollets, who depended on public charity and pious bequests, the Jesuits could rely on a solid financial base that supported their work. In 1625, they landed in New France to assist the Récollets and soon took a leadership role both in the missions and among the clergy. This situation continued until the arrival of the first bishop in 1659 and even beyond this date.

In 1632, after Québec had been captured by the Kirke brothers and then returned to France, the Jesuits came back to run the Récollet missions at Champlain (Trois-Rivières) for the Abenaki, at Tadoussac for the Algonquins, on Georgian Bay for the Hurons and at Île Royale, in Acadia, for the Mi’kmaq.

The cultural gulf between the Jesuits and the Amerindians

In 1635, the Jesuits opened a small school in Québec for the colonists’ sons, alongside a seminary, which, it was hoped, would lead young Hurons to convert and adopt a more sedentary lifestyle. The results were disappointing—of the first six Huron boarders, two fell ill and died, while another returned home, incapable of adapting to the confinement and overly rigorous discipline imposed by the missionaries. The residential school was maintained, but Aboriginal parents hesitated to entrust their sons with the men who wore “black robes.” The school, which gradually added secondary-level classes based on the traditional French “cours classique,” ultimately served to educate French, Canadian-born youth.

In short, the missionaries found little reward for all their trials, suffering, exhaustion and ceaseless conversion work. The cultural and spiritual values of the two groups collided with one another—the Jesuits stood for the order of social classes, strict control of behaviour and unswerving obedience to the Church and the king of France, while Aboriginal populations favoured individual liberty, the comparative equality of the sexes and governing through consensus. The Jesuits hoped that Native boys who had learned the catechism would preach the gospel when they returned to their people; however, in Aboriginal communities, priority was given to the words of chiefs, shamans and elders of both sexes.

Women to the rescue (show)

The Ursulines and Hospitalières arrive at Québec, 1639

Beginning in 1632, the Jesuits wrote up annual accounts of their missions’ progress. Known as Relations, these accounts were sent to France to be published for propaganda purposes. Their aim was not so much to recruit large numbers of settlers, but rather to attract other missionary congregations. The Jesuits sought the aid of nuns who could take on responsibility for the conversion and education of girls. The Ursuline nuns of Tours and Bordeaux—including Marie de l’Incarnation, most notably—were faithful readers of the Relations. They answered the Jesuits’ call and offered their services. It took three long years of negotiating with the authorities, but the nuns eventually won permission to leave for Canada, a country described by Jacques Cartier as “the land God gave to Cain.”

I knew nothing of Canada, and when I heard this word spoken, I believed that it had simply been invented to frighten children.

—Marie de l’Incarnation, Correspondances, To her son, Québec, October 3, 1645

At first, the Ursulines were lodged in an abandoned fur warehouse on the Québec wharf, loaned to them by merchants in the Compagnie des Cents-Associés (Company of One Hundred Associates). The nuns’ mission thus began in these cramped, unsanitary and poorly heated quarters; they had to wait until 1642 for the construction of their convent in Upper Town to be completed. Their first boarders were Algonquin and Innu girls entrusted to them by the other missionaries; a little later, the nuns took in the daughters of settlers. In the 1650s, they started to admit small groups of Huron girls, as well as a few Iroquois, particularly the daughters of converted chiefs, and these latter pupils were described by the sisters as their “heart’s delights.” French and Aboriginal boarders stayed in the same dormitory, ate in the same refectory and played in the same yard. However, when it came to schooling, the Aboriginal girls were taught in separate classrooms, to make it easier to convert them.

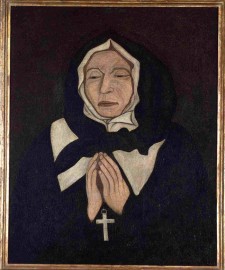

Even though Marie de l’Incarnation showed more understanding of her pupils’ culture than did the Jesuits, she was scarcely more successful. In France, the Jesuits and Ursulines had earned a reputation as outstanding teachers, but in the New World these communities came up against both a linguistic barrier and a completely different view of childhood. In French grade schools and colleges, children were considered to be unfinished adults, imperfect beings who had to be set right, by forcible means if necessary, from early childhood on. In contrast, Aboriginal parents believed that children should be given full freedom, at least until puberty when they were initiated by elders into adult life. Melancholy, sorrow and boredom were considered by the Aboriginals as serious, even mortal diseases. In 1668, after 30 years of experience in the country, Marie de l’Incarnation described the situation in the following words:

Others [Savage girls] are here only as birds of passage and remain with us only until they are sad, a thing the Savage nature cannot suffer; the moment they become sad, their parents take them lest they die.

—Marie de l’Incarnation, Correspondances, To her son, Québec, August 9, 1668

By the beginning of the 18th century, the Ursulines were all “Canadiennes.” The first Canadian-born Mother Superior, Anne Bourdon, was elected in 1700. She surrounded herself with a council composed entirely of nuns born in the country, including her assistant, the novices’ teachers, the classroom teachers, the custodian and the secretary. Around 1725, the role of European nuns had come to an end, and the convent recruited novices among the settlers’ daughters only. These novices were most frequently former boarders who, once they had completed their short course of study, remained at the convent, donning the order’s habit at about the age of 15. Little by little, the congregation abandoned its mission to Aboriginal girls, who were now sent to the Huron village of Lorette, and instead devoted its efforts exclusively to the education of young Canadian girls, enriching the school program with new subjects like history, geography, music and science.

After the British Conquest of 1759, the Jesuits’ college was used as a barracks for British soldiers, and the Sulpicians of Montréal had to seek refuge in France, since the invaders had seized their property, including their colleges. The Ursulines, however, were able to save their institution by displaying tact and flexibility. For example, they added English to the curriculum and accepted the daughters of British officers and newly arrived residents as pupils. The sisters themselves learned English, very much as the first nuns had learned Innu , Algonkin, Huron and Mohawk. Furthermore, an English-speaking sister, Esther Wheelwright, who as a child had been taken captive by the Abenaki, was elected Mother Superior in 1760.

The Ursuline hospital at Trois-Rivières

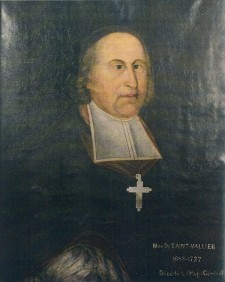

In 1697, Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier, the colony’s second bishop, sent a few Ursuline nuns to Trois-Rivières to establish a convent that would also function as a hospital and a school that took in boarders. The nuns assigned to care for the sick were trained for a few weeks by the Hospitalières at Québec. To direct the institution, the bishop chose Marie Lemaire des Anges, who was already the Superior at Québec. Mother des Anges was loved and respected by the entire Ursuline community, which now numbered some 60 sisters. Unfortunately, the bishop’s choice meant that the colony’s most solidly established educational institution for girls was deprived of its leader.Precarious finances

The king was pleased to have religious congregations go to the colonies, but not at the expense of the state. The motherhouse of each community thus had to rely on its own resources and appeal to the charity of pious laypeople, such as Madame de la Peltrie in the case of the Ursulines; the Duchess d’Aiguillon for the Hospitalières; and Madame de Bullion for the hospital founded by Jeanne Mance in Montréal. Other French benefactors also sent donations. For example, the Ursulines received not only pious bequests but also gifts of textiles, beds, bedding, towels, pharmaceutical products, religious items, preserves, dried fruit and children’s clothes—in short, everything that the missionaries lacked in the new land. In addition, Canadian families often paid their daughters’ boarding school fees with construction material, labour and even tracts of land.

Schooling was free for young Aboriginals. However, their parents considered it a sacrifice to entrust their sons and daughters to strangers whose robes hid everything but their faces and, above all, who had no children of their own to “lend” them in return, in accordance with Amerindian custom.

Despite the charitable donations received by the Canadian missions, the financial situation of the religious congregations remained precarious throughout the French Regime. They were prevented from improving this situation by numerous factors, including the destruction of their buildings by fire, the rigorous climate, poor harvests and unseasonable frosts, the expense of French goods and the high cost of specialized labour for the construction of their colleges and convents. In addition, the state had little concern for the missions, granting the congregations merely 300 to 500 French livres each year. Indeed, according to historian Guy Frégault, the entire annual budget for the colony—between 300,000 and 400,000 livres—represented one fifth of the sums spent on items for the king’s entertainments, including balls, concerts, theatre and comedies, sumptuous banquets and the construction of Versailles. Frégault goes on to say that, in contrast, when the king needed hydrographers, pilots and surveyors to be trained for his own projects, he did not hesitate to finance the founding of Jesuit schools offering courses in mathematics, astronomy, navigation and map making.

An act of humility

Like the Jesuits, who became “pupils of the savages” in order to acquire their languages, the Ursulines also learned to speak these strange, “barbarian” tongues. The king’s orders were that the missionaries should civilize First Nations and have them adopt the ways and language of the French. The congregations were persuaded that this would be easy to accomplish, since Aboriginal people often presented themselves as docile and peaceful . However, Aboriginal parents had no interest in seeing their children become French, and, in any case, the young boarders usually stayed only a few months with the “black robes.” It was thus the teachers who ended up acquiring the languages of their pupils, rather than the other way around.

Jesuits returning from their missions in the hinterlands had some knowledge of Aboriginal languages, either gained through immersion or gleaned from their interpreters, and they taught the nuns what they knew. Sometimes they were aided by schoolgirls, like Marie Amisdoueian, a 17-year-old Algonkin who had learned French with Marie Rollet. This young woman taught her native language to Marie de l’Incarnation, who in turn took it upon herself to train her fellow nuns in this difficult exercise. In 1668, the Ursuline Mother Superior described this effort as follows:

… these barbarous tongues are difficult and, to apply oneself to them, one needs a constant mind. My occupation on winter mornings is to teach them to my young sisters: there are some that have got as far as knowing the rules and being able to analyze the words, provided I translate the Savage for them into French. But to learn a number of words from the dictionary—this is difficult for them, this is thorny.

—Marie de l’Incarnation, Correspondance, To her son, Québec, August 9, 1668

In fact, despite her heavy responsibilities as Mother Superior of the Québec convent, Marie de l’Incarnation had been translating prayers and catechisms into Huron and Algonkin and writing up lexicons and dictionaries since 1660. Sadly, these precious documents have been lost.

Rechristianizing the colonists (show)

Strict control of the population

It was the missionaries’ opinion that the European settlers were too few in number and too scattered over a vast area, far from religious assistance. There was a similar problem in Europe: the convents and grade schools were generally located in towns, while outlying regions received only rare visits from itinerant priests.

The Canadian clergy, which was gradually built up through the efforts of Monseigneur François-Xavier de Montmorency-Laval, the colony’s first vicar apostolic and bishop, wanted to keep an eye on the colonists’ morals and control all aspects of their behaviour. The principal transgressions denounced by Monseigneur de Laval and his successor, Monseigneur Jean-Baptiste de La Croix de Chevrières de Saint-Vallier, were as follows: the selling of alcohol to the Native People by the coureurs de bois, who in so doing committed a sacrilege punishable by excommunication; dances, which represented an opportunity for sin; the lack of modesty showed by women in church; drinking, blaspheming and working on Sundays,by men; and lazy, idle, rude and violent behaviour on the part of children. The clergy forbade drunkenness, profane amusements, games of chance, insubordination and eating meat during Lent. The clergy sought to control the population through various means. They set up pious societies, such as the brotherhoods of Sainte-Famille, Saint-Joseph and Sainte-Anne, to stimulate the Catholic faith among adults. They organized processions, expositions of the Blessed Sacrament and retreats, which complemented the some 150 fast days in the Catholic calendar. For children, the religious communities opened grade schools in towns and in the country. The catechism, exercises in piety and the practice of moral behaviour were considered more important than other subjects, since pupils normally left school after their first communion, at about the age of 11. Boys who showed promise were trained in cabinet-making, farming or artistic crafts, while girls were taught sewing, embroidery and household management.

As the colony gradually developed, other congregations took root in New France. Montréal received the Notre-Dame sisters from France, with Marguerite Bourgeoys at their head, and later saw the founding of the Soeurs Grises (Grey Nuns) led by Marguerite d’Youville. The Sulpicians opened colleges and the Charron brothers, a pious organization dedicated to the care of the sick, the infirm and orphans, ran a charity home that was eventually turned into a hospital with a school for orphans.

The priests of Saint-Sulpice in Montréal

The Sulpicians recruited their members exclusively among the priests at their Saint-Sulpice seminary, in France. In 1657, under the direction of their grand vicar, Abbé Gabriel Thubières de Levy de Queylus, they founded a seminary in Montréal. Acquiring the seigneury of the island of Montréal in 1664, they fulfilled many roles: they were parish priests in the town and its surroundings, Superiors for nuns’ congregations in Montréal, teachers, missionaries and explorers. When the time came for a bishop to be named for the colony, the Sulpician Abbé Queylus was poised to assume this title, while the Jesuits lobbied in support of their candidate, Monseigneur de Laval. This led to major conflict between the two orders.

Abbé Queylus had already assumed the role of grand vicar to the archbishop of Rouen, Monseigneur François de Harlay, and he was certain that the position belonged to him. Since most of the vessels sailing for the colony left from the port of Rouen at the time, the archbishop claimed to have exclusive rights to New France. The Jesuits, however, had been in charge of the Canadian Church since 1632 and had a strong candidate in Monseigneur de Laval, who had studied at the College La Flèche, a Jesuit institution. In the end, the Jesuits won their case and Monseigneur de Laval was appointed to head the Church in Canada.

Monseigneur de Laval and the Canadian Church

In 1661, Louis XIV, who was commencing his personal rule at the age of 23, decided to inject new blood into the colony. The settlement of New France had suffered setbacks as a result of Iroquois incursions, the economy was in ruins and, with the destruction of Huronia, Canadian furs were being diverted to New York. The Hurons were French allies and the principal fur traders. In 1665, at the colonists’ request, the king sent the Carignan-Salières regiment to New France to attack the Iroquois in their own territory south of Lake Ontario. He also sent over more than 800 marriageable young women, in the hope that this would counteract the depopulation of the colony. Most of them were orphans who had been living at the Salpêtrière Hospital, in Paris. Each of them received a “dowry” of 50 livres. Finally, to reaffirm his authority, Louis XIV revoked the powers of the trading companies; created a court of law called the “Conseil souverain” (Supreme Council); gave the colony its first civil code, known as the “Coutume de Paris”; and appointed Jean Talon as the first colonial Intendant.

Encouraged by the king’s support, Monseigneur de Laval devoted himself to building up the Canadian Catholic Church by providing the colony with a clergy worthy of the name. His first achievement was the Grand Séminaire in Québec, built in 1663 and intended to train young clerks for the priesthood. The clerks learned how to administer the sacraments, recite the Divine Office, sing liturgical chants, preach the Word of God to adults and teach the catechism to children. Lacking the necessary funds, Monseigneur de Laval affiliated his foundation with the Séminaire des Missions étrangères, in Paris, which was able to furnish not only financial means, but teacher priests as well. In 1668, the bishop opened the Petit Séminaire de Québec, also known as the Séminaire de l’Enfant-Jésus. The first class was composed of eight young Canadians and six Hurons. They were lodged in the Petit Séminaire but attended the Jesuits’ College for their studies. By 1681, nearly 40 students attended this seminary, studying literature and the classics. They were also offered training in arts and crafts such as cabinet-making, sculpture, painting and gilding of church decorations. The school produced joiners, carpenters, roofers, cobblers, tailors and masons. Those who had a calling became clerks and, if they persevered, might later be admitted to the priesthood.

Two major fires, one in 1701 and the other in 1705, left the Petit Séminaire in a critical situation. However, in 1726, with the arrival of funds and teaching staff from the Séminaire des Missions étrangères in Paris, it became possible for the institution to offer courses in Greek and Latin grammar and literature, as well as in philosophy and theology.

By the end of the 17th century, the three government towns of New France—Québec, Trois-Rivières and Montréal—had a good number of grade schools both for girls and for boys. Québec possessed the Ursulines’ Convent, the Ouvroir de la Providence run by the Notre-Dame Congregation, the Jesuits’ College, the Grand Séminaire and the Petit Séminaire; in Trois-Rivières there was the hospital-school operated by the Ursulines; and Montréal was served by the Sulpicians’ grade schools and colleges for boys and Marguerite de Bourgeoys’ schools for girls, as well as the hospitals and hospices managed at one time or another by Jeanne Mance, Marguerite d’Youville, the Charron brothers and the Hospitalières of Dieppe and of La Flèche.

The Canadian Church continued to develop in rural areas, especially with the establishment of an agricultural school and model farm at Cap Tourmente at the instigation of Monseigneur de Laval. Nearby, the village of Saint-Joachim was endowed with a crafts school coupled with a grade school, where local boys could learn to read, write and count. The master sculptor Jacques LeBlond de la Tour taught sculpting at this institution between 1690 and 1706. The altarpieces in the churches of Sainte-Anne de Beaupré, Château-Richer and L’Ange-Gardien are the work of this master and his pupils.

A social mission (show)

The apostolic work of Marguerite Bourgeoys

Marguerite Bourgeoys arrived at Montréal along with some 200 men and women who were part of the “great recruitment” of 1653. This was an initiative designed to help repopulate the town, which had been steadily losing its inhabitants as a result of Iroquois attacks. The new colonists represented all kinds of professions and rekindled hope in the heart of Montréal’s founder, Sieur de Maisonneuve. Marguerite Bourgeoys was obliged to put off establishing a school until 1658, since there were not enough children in the town. In the meantime, she busied herself with assisting Jeanne Mance at her hospital and visiting families in the settlement.

Marguerite Bourgeoys was a woman of action and travelled back to France several times to recruit new teachers for the Notre-Dame Congregation. Over the years, she founded several grade schools for girls in Montréal, Québec, Trois-Rivières and Louisbourg, as well as on Île d’Orléans. Since the congregation’s rules forbade keeping pupils over the age of 14 at their convents, older girls could not attend grade school. To remedy this, Marguerite de Bourgeoys set up schools called Ouvroirs de la Providence, where young women could learn household skills to prepare them for their future roles as pious mothers. The tireless nun also established the “Mission de la Montagne,” a mission on Mount Royal where young Amerindian girls were taught not only the catechism, but also knitting, sewing, mending and embroidery, so that, as the founder wrote, they might earn a living.

This type of education pleased the colonial authorities, who viewed it as a practical tool for combatting idleness. They made a point of emphasizing the usefulness of the nuns in the Notre-Dame Congregation, comparing them to the Ursulines, who, they said, were good only for showing their pupils good manners and how to curtsey, or for filling the heads of their Aboriginal boarders with overly complicated religious concepts or notions of French that were quickly forgotten when they left the convent and returned to their own people.

Relations between Marguerite Bourgeoys and Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier were tense. The Notre-Dame Congregation was a secular order, but the bishop wanted to make it a regular order, like that of the Ursulines, and impose his own rules on them. Unused to opposition, he was greatly perturbed when the congregation’s founder and her fellow sisters made it clear that they wished to remain independent. Marguerite Bourgeoys held her own against the bishop for 20 years to safeguard the spirit and the letter of her congregation’s rule, inspired by the vie voyagère (or travelling life) of the Virgin Mary. In 1701, shortly before her death, Marguerite de Bourgeoys won her case. The congregation’s nuns were to take simple vows of poverty, chastity and obedience and wear a habit, but the congregation itself remained secular and therefore free to establish itself in towns or in the country to set up schools.

The Charron brothers

In 1692, François Charron de La Barre, a pious layman, founded an association to assist the needy. This association, known as the “Frères de la charité” or the “Frères Charron,” opened a Montréal charity home that became a hospital, the Hôpital Général, two years later.

Marguerite d’Youville and the Grey Nuns

As a young child, Marguerite d’Youville grew up in one of the colony’s most eminent families, being related to the Gathiers de Varennes on her mother’s side. However, her father was heavily in debt when he died, leaving his family in stricken circumstances. In 1722, she married François-Madeleine d’Youville, who, after squandering both his fortune and hers on gambling and alcohol, died eight years later. Left with only a house to her name, Marguerite d’Youville withdrew from the world and devoted her energy to prayer and charitable work. She gathered around her women like herself who were poor, but who shared her ideals. This was the nucleus of the Congrégation des Soeurs de la Charité de l’Hôpital général de Montréal, which she eventually founded in 1747.In the meantime, the 1740s were very difficult years for Marguerite d’Youville. The Sulpicians, who were the spiritual advisors of Montréal, wanted Madame d’Youville and her followers to replace the Charron brothers and take over the direction of the Hôpital Général, which was experiencing serious problems. It was not an easy undertaking, especially since certain prejudices died hard in the town. The inhabitant, who nicknamed the women the “Grey Nuns,” believed that Marguerite d’Youville would continue her husband’s disreputable ways, since he had been known as a brutal, dishonest merchant, a gambler and inveterate drinker. However, as the population became aware of the need for the apostolic work she was doing and her zeal in helping the poor, the situation improved. The Soeurs de la Charité were even able to open a wing for “fallen women,” as they were called at the time, and thus modified the hospital’s vocation, since it had been reserved for men until then.

When Marguerite d’Youville took control of the hospital in 1747, the establishment was bankrupt and burdened with a debt of over 40,000 livres. She worked tirelessly to restore the hospital’s viability through every imaginable means— weaving, producing candles and communion wafers, curing tobacco, baking and selling bread, and marketing produce from the sisters’ farm.

Marguerite d’Youville accepted society’s rejects—those who would be turned away from other hospitals: abandoned children, the mentally disturbed, orphans, disabled soldiers, the elderly and lepers. Anyone who was able to help was put to work, whether it was as tailors, cobblers or bakers. She even hired British soldiers as farm workers or orderlies, and these men taught the sisters English. Her resourcefulness enabled her social mission to survive one of the worst periods in the history of New France, marked by epidemics, bad harvests, war and, as of 1763, the perturbations accompanying the advent of British rule.

Acadia and Louisiana (show)

Jesuits, Récollets and Capuchins in Acadia

Acadia, which guarded the eastern entrance to the continent and was thus continuously targeted by England, was part of New France along with Canada and Louisiana. The territory covered by Acadia and what is today the state of Maine was occupied by three Algonquian nations: the Mi’kmaq, the Maliseet and the Abenaki. There were fitful attempts by the French to colonize the region—led by the Marquis de la Roche on Sable Island in 1578, 1584 and 1598, and by Pierre Du Gua de Monts on Île Sainte-Croix in 1604 and at Port Royal in 1606. These expeditions’ lack of success was attributable to a combination of circumstances: a poor choice of sites, disruptions related to the succession of French rulers, attacks by the English and, finally, the ravages of scurvy, a disease that decimated the volunteer troops. Nevertheless, these attempts enabled the French to form solid friendly relations with the region’s Aboriginal populations, who remained loyal to the Acadians—that is, the colonists who eventually settled here—right up to the Deportation of 1755.

The first missionaries were, as usual, the Jesuits, who arrived at Port Royal in 1611 to work with the Mi’kmaq. Between 1629 and 1632, during the Kirkes’ occupation of Québec, the Jesuits set up missions on Cape Breton Island and Miscou Island, at Chignecto, Miramichi, Richibucto and Chedabucto, and along the Bay of Gaspé.

The Récollets came to Port Royal in 1619 with the intention of evangelizing the Maliseets. Father Félix Pain became the priest at Beaubassin, while Father Bonaventure served in the Minas Basin.

The Capuchins also came to Acadia, acting as chaplains for the troops billeted there as well as for the families of fishermen who had settled along the shores. In 1633, the Capuchins opened a seminary at La Have, a port situated west of present-day Halifax. Two years later, they transferred to Port Royal. At that time, about 30 Mi’kmaq and Abenaki boarders, as well as the sons of the first French inhabitants were attending the school.

In 1644, Madame de Brice, a widow from Auxerre, France, travelled to Acadia to take charge of a school for Native girls. Two of her sons, Léonard and Pascal de Brice, were Capuchin fathers and they assisted her in this undertaking. She had at her disposal a budget of 1,500 livres, donated by Queen Anne of Austria, the wife of Louis XIII and the mother of Louis XIV. Madame de Brice also worked as a tutor for the children of the regional governor, Charles de Menou d’Aulnay. But following his death in 1650, she was harassed by his successor, Emmanuel Le Borgne, who was one of d’Aulnay’s creditors. She returned to France around 1653, and her school project was never completed.

Despite the many difficulties encountered by the missionaries, Acadia remained a mission territory until the Deportation of 1755. The British, who had controlled Acadia since the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, tolerated the Catholic faith in this region, as well as the presence of Catholic missionaries. For example, Father Antoine Simon Maillard, a priest from the Séminaire des Missions étrangères in Paris, worked with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia; Father Sébastien Râle served the Abenaki living along the Kennebec River; and Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre ministered to the Acadians who remained at Beaubassin after the Deportation, traumatized by the expulsion and separation of families. With the help of their Aboriginal allies, the missionaries continued to serve the fugitive Acadians, who lived scattered in the woods, fearing British pursuit.

Discord among the missionaries of French Louisiana

Founded by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville in 1700, Mobile was the first capital of French Louisiana, but early on it experienced many difficulties, including wars with Native people, administrative clashes, financial problems and disputes among the clergy. The seat of government in Louisiana was subsequently moved to New Orleans. The colony belonged to the Compagnie des Indes, which was obliged to finance parishes and missions by paying out fixed annual sums, as well as allowances for transportation and supplies. In exchange, the company was granted complete control of trade.

The Jesuits established a mission among the Illinois in 1690. Eight years later, priests from the Séminaire de Québec came to a nearby village inhabited by the Tamaroa branch of the large Illinois family. The Jesuits at once protested this injustice, believing that other orders were trying to have them expelled from North America. However, the Séminaire priests had gone to Illinois country with the approval of Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier and, since he continued to support them, an archiepiscopal court granted them the right to stay. This decision was a matter of disagreement for several years.

In 1721, the Capuchins were given the jurisdiction of New Orleans by the Compagnie des Indes, and this sparked an open conflict with the Jesuits. Five years later, Ignace de Beaubois, Superior of the Jesuit missions, negotiated with the company and obtained both permission to open a mission in New Orleans and the promise of financing for the Ursulines, who wished to establish a school for girls, the first in the Mississippi Valley. In exchange for these privileges, he gave his word that he would undertake no project without the Capuchins’ approval. The Ursulines, who were the traditional allies of the Jesuits, arrived in New Orleans in 1727 and chose Father Beaubois to be their spiritual advisor. Their decision aggravated the discord between the Jesuit Superior and the Capuchin parish priest of New Orleans, Raphaël de Luxembourg, who feared Jesuit interference in the region.

Called back to France in 1728, Father Beaubois had to justify his actions. He firmly denied having encroached on the Capuchins’ jurisdiction. As of 1731, Louisiana was administered directly by the king, who named Le Moyne de Bienville as governor of the territory. With the support of de Bienville, who was his friend, Father Beaubois returned to New Orleans, but when conflicts arose once more between the Capuchins and the Jesuits, he went back to France for good in 1734. Jean-Frédéric Phélypeaux, Comte de Maurepas, the French Minister of the Marine, wrote that Beaubois’ departure would bring greater tranquillity to the Church in Louisiana, although he recognized that the missions in Mississippi Valley owed much to him.

Like Acadia, Louisiana remained a mission territory for a long time, shared uneasily by Jesuits, Capuchins and the priests of the Séminaire de Québec. The evangelizing missions, although established by the late 17th century, never had any real success. Historian Guy Frégault writes that boys were still not going to school in the mid-18th century.

The Ursulines in New Orleans

In 1727, a group of 11 Ursulines coming from various convents in France were mandated by Monseigneur de Saint-Vallier to establish a hospital and school in New Orleans. Under the direction of Father Beaubois, the nuns took in colonists’ daughters as boarders and also taught the “savages, negresses and slaves.” The Compagnie des Indes had promised to build them a convent within six months of their arrival, but it was not finished until seven years later. Like the Ursulines of Québec, they spent the first years in great deprivation and in very cramped quarters.

Louisiana was still sparsely populated in 1744. There were about 4,000 European inhabitants and an equal number of black slaves. In 1766, the king of France offered the colony to Spain, in recognition of its joining the alliance against Great Britain during the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). Louisiana was returned to France in 1802, but Napoleon Bonaparte sold it to the United States the following year.

Detroit and Pays d’en haut

Detroit was founded in 1701 by Antoine de La Mothe, Sieur de Cadillac, on the narrows between Lakes Huron and Erie. Its early years were difficult, especially since no one, including Jérôme Phélypeaux, Comte de Pontchartrain, the French Minister of the Marine, and Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil, the Governor of Canada, believed in its future. It was widely known that Cadillac’s intention was to make a personal fortune in the fur trade rather than to establish a settlement capable of defending this region against the colony’s traditional enemy, the British.

Tensions in the area were exacerbated not only by administrative conflicts and disputes provoked by the quarrelsome Cadillac, but also by territorial disagreements among the missionaries. The Récollet Father Constantin Delhalle established the Sainte-Anne Mission at Fort Pontchartrain, the first fort at Detroit, and worked there as a parish priest. To the north, the Jesuit fathers, Étienne Carheil and Joseph-Jacques Marest went to the Saint-Ignace Mission at Michilimackinac to serve the Ottawas and the Hurons. Father Carheil was responsible for converting the Hurons’ grand chief, Kondiaronk, who played an important role in negotiating the Great Peace of Montréal in 1701. Father Marest went on to work with the Sioux of the Upper Mississippi. For their part, priests from the Séminaire des Missions étrangères associated themselves with the mission at Fort Saint-Louis in Illinois country. During the same period, from 1690 to 1701, the situation was further complicated by an increase in the number of Iroquois raids and by preparations for the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1713). Eventually, despite the pessimistic prediction of the French administrators, Detroit grew into one of North America’s major cities.

The vast hinterland where the fur traders travelled was known as the Pays d’en haut. Missions in the Great Lakes region had been started in the 1630s, through the efforts of Jesuit Jean de Brébeuf. Evangelization was difficult, since the Laurentian Coalition, formed by the Algonkins, Innu and Hurons, suffered losses at the hands of the Iroquois Confederacy, which was armed by the Dutch and the English. Native allies were also victims of severe epidemics that swept through their communities. So many succumbed to smallpox and dysentery in 1634, malignant influenza in 1636 and another smallpox epidemic in 1639, that a population estimated by the missionaries to be about 33,000 when they arrived was reduced to 12,000.

In 1649, the Jesuit Charles Albanel disembarked at Québec before travelling to Montréal. He then spent a dozen winters at Tadoussac, among the Innu and Algonkins at the Saint-Croix Mission. Around 1670, he worked with other Innu communities on the North Shore of the St. Lawrence, and with the Mistassini Cree at Lake Saint-Jean. Later, he ventured to Hudson Bay and Wisconsin. According to certain sources, he had an extraordinary gift for languages.

In 1655, the missionary Claude Dablon arrived at Québec and made his way to the Great Lakes region, to serve the Onondaga Iroquois. The following year, he founded the mission of Saint-Marie de Gannentaha, where he worked until 1669. He was then made Superior of the Western Missions, with their headquarters in Sault Ste. Marie, in what is now Ontario.

The Jesuit father, Jacques Marquette, came to Québec in 1666 and went to Trois-Rivières to study the Montagnais language for a year. In 1668, he made his way to the Ottawas’ mission at Sault Ste. Marie, where nearly 2,000 Algonkins were living. He then founded the Saint-Esprit mission on the shores of Lake Superior in order to serve the Ottawas and Hurons. It was there that he met the Illinois, who were at war with the Sioux. When the Illinois were defeated, they retreated towards Lake Michigan, to the straits of Michilimackinac. Here, in 1671, on the north shore of the straits, Marquette founded the Saint-Ignace mission. He then met Louis Jolliet, the adventurer assigned by the Governor to explore the Mississippi River and discover its mouth. In 1673, the two men went down the river by canoe, covering nearly 1,300 kilometres, until they reached the present-day borders of Arkansas and Louisiana. They were enchanted by the discovery of new landscapes and exotic plants and birds, as well as the sight of bison herds number over 400 animals.

At the mouth of the Iowa River, they encountered the Peoria branch of the Illinois Confederacy and received a warm welcome. The expanses of the Missouri and Ohio rivers amazed them. But at one point, they could go no further. The Aboriginals who traded with the Spanish showed such hostility that the explorers realized they had to turn around. However, thanks to Louis Jolliet and Father Marquette, it was now known that the Mississippi flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, rather than leading to the “China Sea,” (Pacific Ocean), as had been hoped from the time of the earliest inland explorations.

Uncertain results (show)

New France remained a mission territory throughout the French regime. The missionaries were well educated, passionate about theology and philosophy, and ready to confront great hardship to achieve their goals. They had to deal with fatigue, suffering, long and dangerous trips, exhausting portages, harsh winters and lack of hygiene, but nothing could stop them. However, they had little understanding of the immense cultural and spiritual gulf that separated them from the continent’s indigenous inhabitants. They refused to admit that the age-old beliefs, rituals and spiritual practices of the Native people were valid. From the time of their first contacts, the “black robes” tried to turn drumming into liturgical chants, to trade the shaman’s harangue for rosaries and the Sign of the Cross, to impose monogamy and replace a Native hunting and fishing paradise with another one, filled with angels.

The missionaries, teaching nuns and authorities had recourse to many strategies to persuade Aboriginals. The king, for instance, promised to “naturalize” and make them full French subjects if they accepted baptism and conversion. The Ursulines took imaginative steps in their efforts to civilize their “little savages.” The nuns gave their Aboriginal pupils French first names at their baptism and integrated them with French pupils in the dormitory and refectory, requiring them to dress and wear their hair as their European classmates did. However, Aboriginal boarders rarely stayed with the nuns for more than a few weeks or months. In the end, it was the nuns who had to learn their pupils’ language and not the other way around. The same situation prevailed among the male missionaries, who preferred hearing the converts praise God in their “barbarous” tongues to seeing them desert their missions. In certain extreme cases, the missionaries went so far as to trade weapons with the Hurons in exchange for their conversion, a practice that caused discord in Native families and villages.

Finally, it was decided that the populations at certain missions should become sedentarized. In the late 1670s, the Abenakis settled in two villages south of Trois-Rivières, Saint-François (Odanak) and Bécancour (Wôlinak). In 1697, the Hurons established a village at Wendake, near Ancienne Lorette. In the 18th century, the Sulpicians brought together Mohawks and Oneidas who had left the League of Five Nations; two new villages were created for them—Saint-Régis (Akwesasne) in 1747 and La Présentation (Oswegatchie) in 1749.

The lack of understanding shown by the teaching nuns and missionaries with regard to the culture of the people they hoped to convert, civilize and make more like the French was not the only factor in their difficulties. The missionaries were also associated with the new diseases that decimated Native populations. On the whole, the success of conversion efforts in New France was quite modest, according to the European sources on which we must rely for such information.

Suggested readings (show)

BEAULIEU, ALAIN. “Réduire et Instruire : deux aspects de la politique missionnaire des Jésuites face aux Amérindiens nomades (1632–1642),” in Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, Vol. XVII, No.1-2, 1987,139-154.

DELUMEAU, JEAN. Le catholicisme, entre Luther et Voltaire, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1979.

FRÉGAULT, GUY. La Civilisation de la Nouvelle-France 1713–1744, Montréal: Fides, 1969.

FRÉGAULT, GUY. Le Grand Marquis, Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil et la Louisiane, Montréal: Fides, 1952.

GOSSELIN, AMÉDÉE. L’instruction au Canada sous le Régime français (1635–1760), Québec City: Imprimerie Laflamme et Proulx, 1911.

MARIE DE L’INCARNATION. Correspondance, edited by Dom Guy Marie Oury, Solesme: Abbaye de Saint-Pierre, 1971.

MÈRE ST. AUGUSTIN DE TRANCHEPAIN. Relation du voyage des premières Ursulines à la Nouvelle Orléans et de leur établissement en cette ville. Par la Rév. Mère St. Augustin de Tranchepain, Supérieure. Avec les lettres circulaires de quelques-unes de ses Sœurs, et de la dite Mère. Nouvelle York, Isle de Manate: De la Presse Cramoisy de Jean-Marie Shea, 1859.

MGR DE ST-VALLIER. Estat present de l’Eglise et de la colonie françoise dans la Nouvelle-France, Paris: chez Robert Pepie, fontaine S.Séverin [MDC.LXXX.VIII], reprinted in 1965.

PLANTE, HERMANN. L’Église catholique au Canada (1604-1886), Trois-Rivières: Éditions du Bien Public, 1970.

SAGARD, GABRIEL. Le Grand Voyage du Pays des Hurons, Leméac Éditeur, 1990.

The on-line version of the Dictionary of Canadian Biography provides biographies of the following people:

Joseph Le Caron, by Frédéric Gingras

Pacifique DuPlessis, by G. M. Dumas

Gabriel Sagard, par Jean de la Croix Rioux

Gabriel Thubières de Levy de Queylus, by André Vachon

François de Laval, by André Vachon

Madame De Brice, by René Beaudry

Nicolas-Ignace De Beaubois, by C. E. O’Neil

Jean de Brébeuf, by René Latourelle

Charles Albanel, by G. E. Giguère

Claude Dablon, by Marie Jean-d’Ars Charrette

Jacques Marquette, by J. Monet