The Explorers

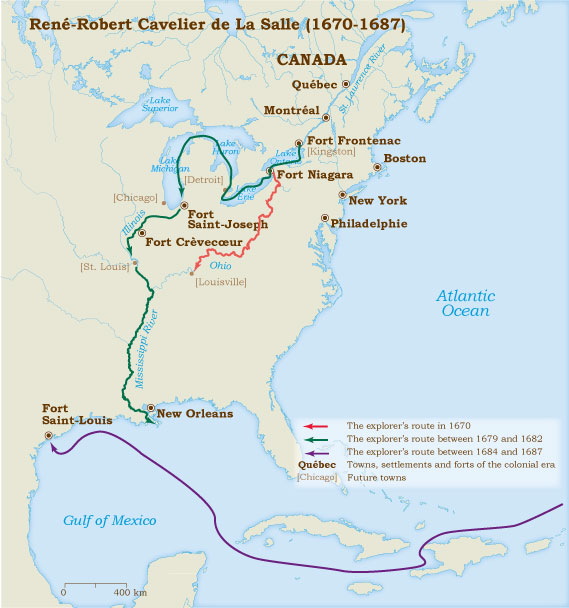

René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle 1670-1687

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle was born at Rouen, in Normandy, on the twenty-first of November, 1643. He belonged to a wealthy middle-class family. At the age of fifteen, he was enrolled in the Jesuit noviciate of Rouen, and he took his vows in 1660. Five years later he asked to be sent abroad as a missionary. However, he lost his vocation and invoked “moral weaknesses” as his reason for asking to be released from his vows. On the twenty-seventh of March, 1667, he found himself a free man. This was the background to the start of a career which would eventually lead him to discover the mouth of the great Mississippi, “Father of Waters”.

Route

The China Obsession

La Salle arrived in New France in 1667 with no trade and no money. He may have been influenced to make the journey by the fact that his brother Jean, a Sulpician priest, had been living at Ville Marie (Montreal) for a little less than a year. No sooner had young La Salle arrived than he was granted a piece of land in the western part of the island of Montreal. He became so obsessed with the search for a route to the Orient that his seigneurie (estate) became jokingly known as ‘La Chine’ (French for China.)

Exploration Frenzy

By July, 1669, La Salle was ready to start searching for the “Vermilion Sea” (the Pacific Ocean), which he hoped to reach by way of the Ohio River. Such was his enthusiasm that he who “would lief permit no other man the honour of finding the way to the South Sea and thence to China” sold his estate back to the people who had granted it to him, fitted out five trading canoes and hired fourteen men. As exploration also had its religious side, for evangelizing the Amerindians, the Church took an interest, and so the Sulpician Dollier de Casson accompanied La Salle with three canoes and seven recruits recently arrived from France. De Casson also brought along an invaluable companion, the Abbé René de Bréhan de Galinée, whose task was to draw maps of their discoveries.

It did not take La Salle’s fellow travellers long to realize that their leader was incompetent. He could speak neither Algonquian nor Iroquoian. According to Galinée, La Salle “was undertaking this journey almost in a daze, more or less not knowing where he was going.”

By September the party reached the north shore of Lake Erie. On the first of November, 1669, La Salle announced that he was returning to Ville Marie because, so he said, of ill health. He disappeared into the bush and resurfaced in the colony only at the end of the summer of 1670. He was later to claim that he had meanwhile discovered the Mississippi ahead of Jolliet and Marquette.

Emissary and Protégé of Frontenac

In 1673, the Governor of New France, Louis de Buade de Frontenac, sent La Salle as his emissary to Lake Ontario. There La Salle convened a council of the chiefs of the Iroquois nations, who granted him permission to build a fort (Fort Frontenac) at Cataracoui (Cataraqui, site of Kingston.) Having acccomplished his mission to ensure that New France would have control of the fur trade on the Great Lakes, La Salle set off for France to seek more. He returned with letters of nobility, and the seigneurie of Cataracoui was created for him in exchange for certain undertakings on his part.

La Salle was still not satisfied. Back again in France in 1677, he bribed an important person of influence and presented an untrue, self-serving report of the discoveries he claimed to have made. By such means he obtained, on the twelfth of May of the following year, the exclusive right to explore the area between Florida and Mexico. This right was later extended to allow him to “build forts at the places where he may consider them necessary and to benefit from the same conditions as at Fort Frontenac.”

Builder of Forts

La Salle was back again in the colony on the fifteenth of September, 1678, with some thirty greenhorns from France, among them Father Louis Hennepin of the order of Récollets. Hennepin became the first person to describe and draw a picture of the Niagara Falls. While some of the men were erecting the walls of Fort Conti (or Fort Niagara) at that spot, others were at work building a brigantine, the Griffon. On the seventh of August, 1679, the little vessel set sail from Niagara on a course for Michillimakinac (Mackinac) where it dropped anchor twenty days later.

After making sail towards Baie des Puants (Green Bay) the Griffon was despatched back to Niagara and La Salle continued exploring Lake Michigan by canoe. On reaching the mouth of the Miami River (St. Joseph) he built Fort Miami. In January, 1680, his party reached the site of the present-day city of Peoria, Illinois. There he began to erect Fort Crèvecoeur (Fort Heartbreak.) While the construction was underway, disaster struck Fort Niagara, which was destroyed by fire. As for the Griffon, it was never heard of again.

Louisiana

The expedition which set out from Fort Crèvecoeur in January, 1682, comprised twenty-three Frenchmen and eighteen Amerindians. They made their way southwards by the Chicagou (Chicago), Renard (Fox) and Illinois rivers. By February they reached the Mississippi near the site of present-day Memphis, and there La Salle ordered the building of a small fort, Fort Prud’homme.

On the sixth of April they finally caught sight of the mouth of the Mississippi. Three days later, near to where Venice, Louisana, now stands, La Salle, dressed up in a gold-laced red cloak, had a cross planted and a plate buried under it bearing the following inscription: “In the name of Louis XIV, King of France and of Navarre, this ninth of April, 1682.” The official report of the ceremony records the words proclaimed by the explorer who had just extended New France as far as the confines of the Spanish Empire:

“I, René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle, by virtue of His Majesty’s commission, which I hold in my hands, and which may be seen by all whom it may concern, have taken and do now take, in the name of His Majesty and of his successors to the crown, possession of the country of Louisiana, the seas, harbours, ports, bays, adjacent straits, and all the nations, peoples, provinces, cities, towns, villages, mines, minerals, fisheries, streams and rivers, within the extent of the said Louisana.”

Death in Texas

The French monarch, on hearing of La Salle’s discovery, dismissed it as “utterly useless”. Nonetheless, Louis XIV was misled by false maps which placed the Mississippi near the Rio Grande and New Spain. Consequently he commissioned La Salle to establish a French colony in Louisiana. On the following twenty-fourth of July, two hundred and twenty-eight recruits, including several women, set sail from La Rochelle aboard four ships. Their objective, though they did not really know where they were going, was to find the Mississipi by way of the Atlantic, the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

Sickness, shortage of supplies and drinking water, the loss of one of the vessels and the departure of another for France, the death or desertion of many of the men, all compromised the project to found a colony up the Mississipi.

By February, 1687, La Salle’s party was reduced to thirty-six persons. Bad-tempered, haughty and harsh, he alienated even those who had remained faithful to him to the end. He died in the land that is now Texas, shot dead at point blank range. It was the nineteenth of March, 1687. Three of his companions had been murdered just before him. The conspirators who committed the murders then set about killing one another.