2000s Excitement and Innovation

The 2000s saw a brand new group of artists join the print studio. The open studio, a concept initiated decades earlier, continued to bring Southern artists North to work elbow-to-elbow with Inuit artists. Additionally, more formalized relationships were tried with Nunavut Arctic College’s fine arts program in Iqaluit as well as with the Inuit Art Foundation, Ottawa. From these and other efforts, a wider pool of Cape Dorset artists, both young and old, began to create increasingly daring, reflective and eloquent drawings. These new artists included Anirnik Ragee, Mialia Jaw, Ningeokuluk Teevee, Jutai Toonoo, Papiara Tukiki, Annie Pootoogook, Itee Pootoogook and Tim Pitsiulak.

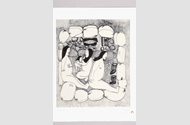

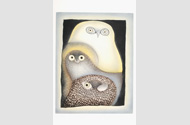

Artists already active (such as Shuvinai Ashoona, Arnaqu Ashevak, Kavavaow Mannomee and Kakulu Saggiaktok) took on a more prominent role in the studio and continued to develop in exciting directions. Senior artists (principally Kenojuak Ashevak, Kananginak Pootoogook, Pitaloosie Saila and Ohotaq Mikkigak) continued to anchor the studio with consistently strong images.

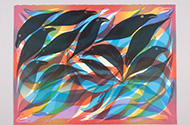

The lithography studio was operated by Pitseolak Niviaqsi and Niviaksi Quvianaqtuliaq, who challenged themselves with more technically difficult print techniques. Rainbow colours, metallic inks, chine collé and litho washes helped bring to life the novel work emerging from the drawing studio, and revealed new dimensions in the work of established artists such as Kenojuak Ashevak. the main printmakers in the stonecut and stencil studio included Kavavaow Mannomee and Qiatsuq Niviaqsi, Arnaqu Ashevak and Ematulu Saggiak.

In 2005, the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative began to work with Atelier GF — a Toronto-based, collaborative print studio — to create screen prints, or serigraphs of Cape Dorset prints. Serigraphs were released in the 2009 annual collection, offering artists yet another medium in which they could express their graphic arts.

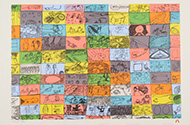

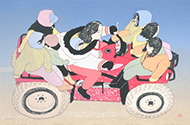

The younger generation of Cape Dorset artists explored themes and artistic approaches seldom seen in previous annual collections. With disarmingly frank pictures of everyday life in the Arctic — a family crowded onto an all-terrain vehicle, rhythmic all-over designs, and “snapshot” close-ups of tools and people — Cape Dorset artists were challenging the artifices of the past, breaking with romantic illusions, and speaking more directly with their audience — a new audience. While never abandoning their characteristic elegance and finesse, the works of many senior artists (such as Kananginak Pootoogook, Pitaloosie Saila and Ohotaq Mikkigak) moved in unexpected directions, too.

Throughout the decade, the sizes of annual collections remained relatively constant, at roughly 30 prints (not including special commissions), with as many as 12 artists — a mixture of young and old — represented in a collection. To help broker this transition to newer styles or untried themes, the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative introduced “spring releases,” small collections of some of the studio’s more daring art.

As the decade drew to a close, the world’s media turned their lenses upon Cape Dorset as the studio celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2009, an event marked by a flurry of exhibitions and publications. Looking forward to the next 50 years, Jimmy Manning wrote that “the challenge for the newer artists is to move on and find their own way ahead.”