On May 27, 2021, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation announced that the unmarked graves of Indigenous children had been found at the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. Kwaguʼł master carver Stanley C. Hunt was stunned at the news, as were people across Canada.

Hunt responded by creating a massive red cedar sculpture that now stands in the Canadian Museum of History as a monument to the children who never returned from Canada’s residential schools.

Inspired by injustice

Stanley C. Hunt’s own family was directly impacted by the tragedy and violence of the residential schools — his parents and two older siblings were forced to attend. He was himself removed from his community as part of the “Sixties Scoop,” when many Indigenous children were taken away and raised in settler families.

Hunt heard the news from Kamloops while working on a memorial pole with his nephew, Mervyn Child. He recalls, “I was working on another memorial pole in my backyard where I do totem poles. Mervyn and I stopped and we listened to it. And it’s hard to describe a moment like that, when you hear that type of news. We listened to the whole broadcast, and we looked at each other and we were both emotionally distraught.” Hearing about the deaths of so many children inspired Hunt to create a memorial sculpture for them.

Stanley Hunt and Mervyn Child.

Canadian Museum of History, IMG2023-0309-0036-Dm

A carving to bear witness

The Monument is not a traditional totem pole or memorial pole. It’s unique.

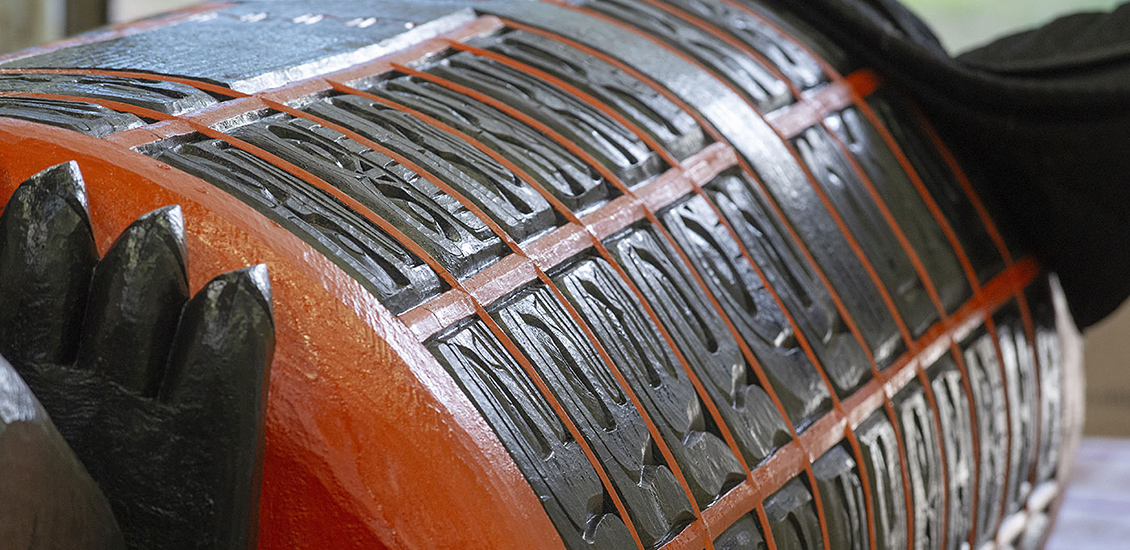

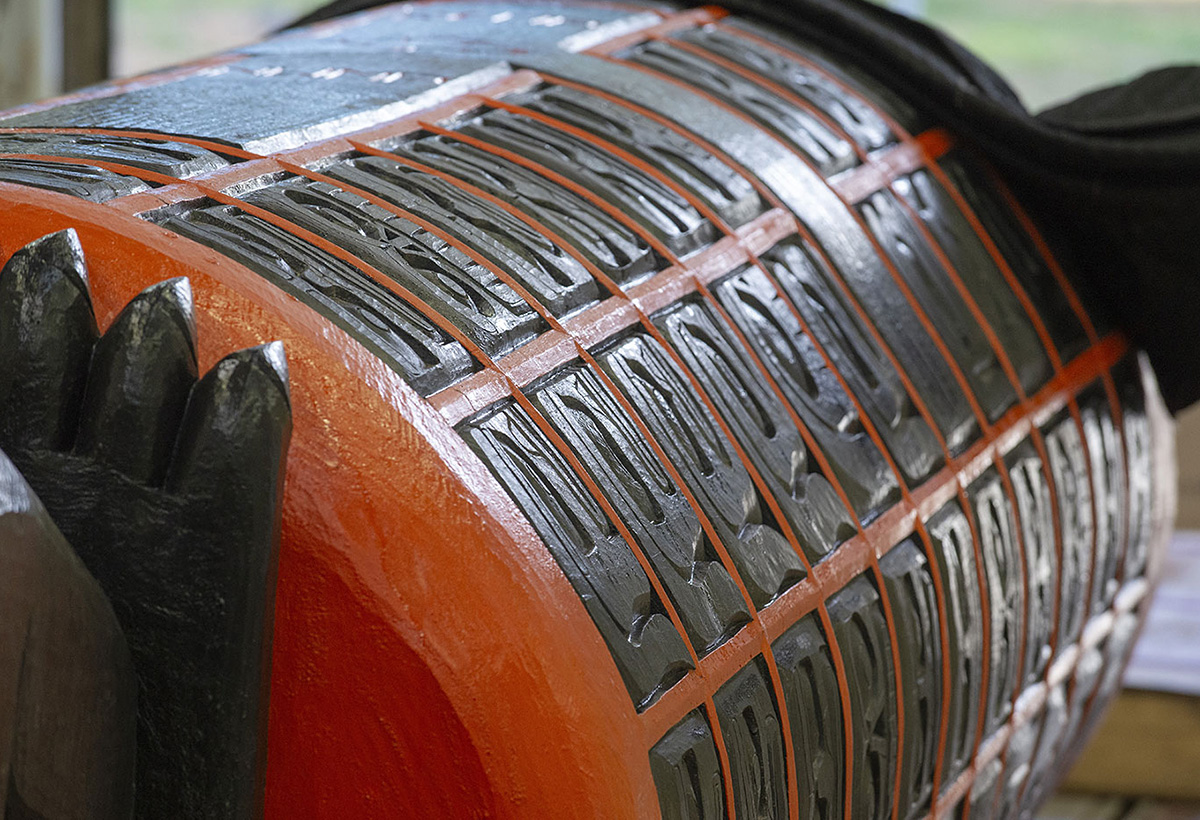

Carved from a tree trunk 18 feet tall and 4 feet wide, it features 130 unsmiling children’s faces beneath a large raven that looks down on them. Emblems such as the maple leaf, cross, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and North-West Mounted Police acronyms are carved upside down. The whole is painted black and orange.

The Monument was carved and transported lying down. It will be raised upright for the first time when it is installed at the Museum.

Canadian Museum of History, IMG2023-0309-0043-Dm

Hunt talks about the importance of the raven: “The raven’s cradling the seed of life in his beak, and his wings aren’t fully extended out, they’re more down so as to comfort the children. To bring them home. He’s calling for their spirits to come home.”

The many faces are there to reflect the scale of the harm and the deaths. They are all different, reminding us that every child who was sent there was an individual – valued, loved, full of potential. Hunt says: “They all had names, they could all have had careers. We don’t know what they could have become. They could have become artists. They could have become writers, painters. They could have become premiers, doctors, lawyers, could have been anything. But they weren’t given a chance to do that.”

Cross-country journey

Moving the monument across the country from Tsakis (Fort Rupert), BC to Gatineau, Que. was a huge undertaking. The Canadian Navy, Coast Guard, Army and RCMP all contributed time, effort, vehicles and personnel. Hunt says, “I personally, I don’t know of anything like this that has ever happened that had this much support by the RCMP, the Coast Guard, the Canadian Navy. The Canadian Army brought it from Vancouver to Regina on the back of one of the army trucks.”

Throughout its journey, the monument was uncovered so the children’s faces could see. Hunt says, “I believe that totem poles all have their own spirit. I want them to see this entire journey.”

Hunt recalls its arrival at the Museum: “We did drum it and sing it into the Museum, at the back, in the delivery dock. We were all dressed in our regalia, and we’re helping the truck bring it in and singing.”

The monument arriving at the Canadian Museum of History.

Canadian Museum of History, IMG2023-0309-0003-Dm

Curator Kaitlin McCormick describes the collective effort involved in receiving the Monument: “Stan invited Museum staff to help wash the monument. We were all taking warm water and washing it, because it had been on the road. And I think everyone here at the Museum who I saw felt overwhelmed with emotion at being involved in this amazing event.”

Truth for reconciliation

The many distinct faces and striking imagery on the sculpture make it at once a compassionate work of remembrance and an unstinting holding-to-account of the governments and churches responsible for the residential school system.

Stanley C. Hunt says, “I felt I was hugely honoured that the Museum would even consider having a piece that is probably going to be pretty controversial in its lifetime. Because I don’t know of any monument anywhere in the world that has a cross deliberately made upside down. It’s not to insult anybody, either. It’s to mark a very dark time in history where some very, very bad decisions were made.”

Museum staff joined the artists in cleaning and touching up the paint on the monument after its long journey across Canada.

Canadian Museum of History, Kaitlin McCormick

Its sheer size and presence are powerful. McCormick says, “Having the opportunity to stand next to it and to see the size of it — it’s striking in the sense that you realize how our history needs to be understood and felt. I think what’s so special about it is that it really is a tangible object that will allow Canadians and visitors to connect to the history of residential schools. I believe that’s going to give us a focal point to understand, to discuss this story.”

Visitors to the monument become a part of the process of recognizing and reckoning with the harms of the past. The monument invites us to become witnesses to truth, to contribute to a future of reconciliation. Hunt says, “I think from what I’ve witnessed so far — you know, from Port Hardy to Ottawa — I believe that it’s helping people.”

Listen to Stan’s episode of Artifactuality to hear more about his story, his monumental sculpture, and the importance of truth-telling about residential schools to advance reconciliation in Canada.

Download and subscribe to Artifactuality wherever you get your podcasts.

Steve McCullough

Dr. Steve McCullough is the Digital Content Strategist at the Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum. His work in digital storytelling involves compassionate and evidence-based efforts to address history, meaning and identity in our fragmented and polarizing, but also vibrant and interconnected, online environment.