Charlotte Nolin struggled to express her gender identity for years. She’s a Métis Elder who was born in Winnipeg in 1950. She was assigned a male identity at birth, but by the age of 6, Charlotte knew she wasn’t a boy.

When she was 17, Charlotte allowed herself to publicly embrace her gender for the first time — but at the age of 23 she went back into the closet, fearing for her safety. She remembers, “Fifty years ago, I was not allowed to walk out in public during the day because I’d be met with violence. And so, myself and most of my sisters, we came out at night when it was dark so we wouldn’t meet so much violence. And there was still violence attached to it.”

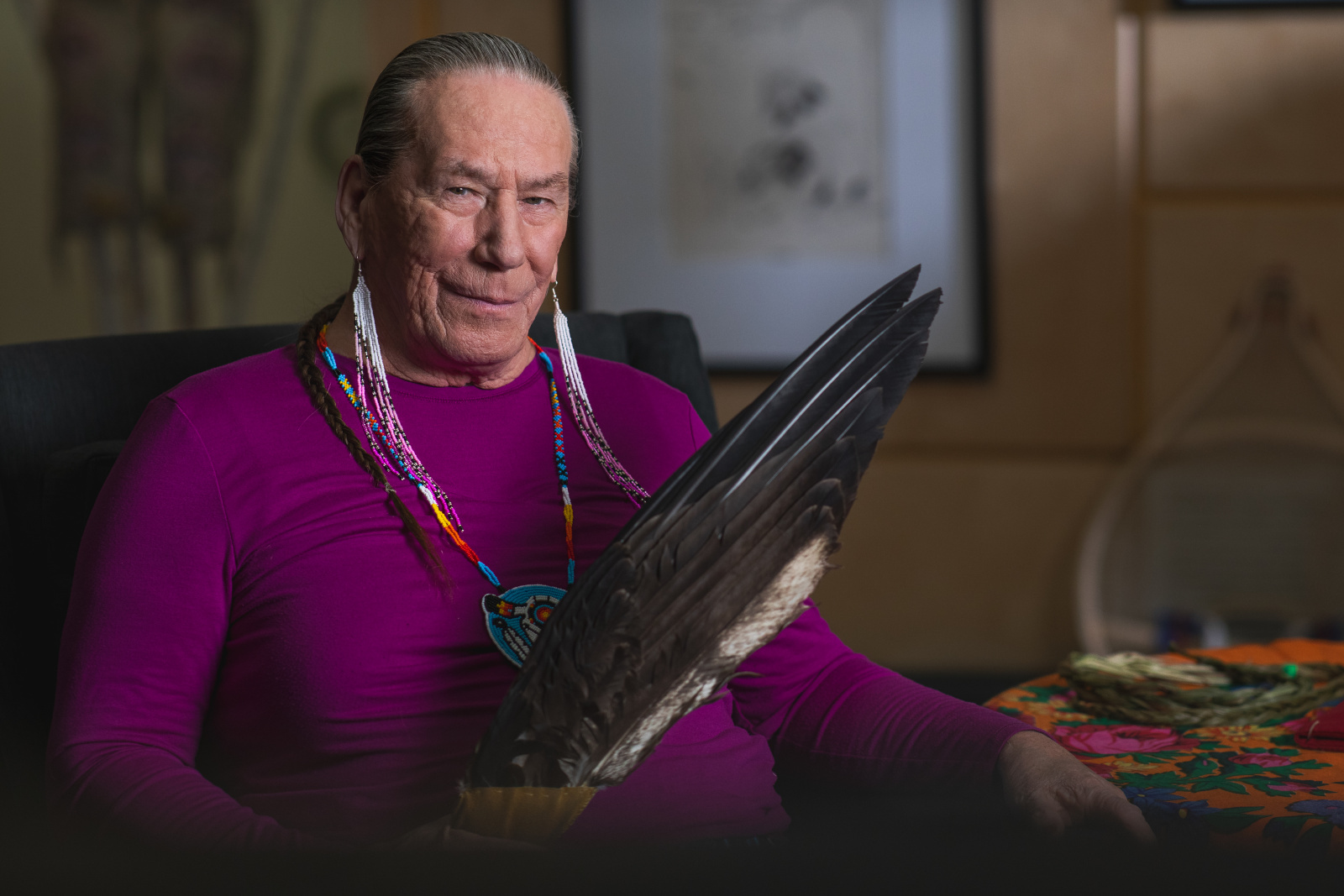

Charlotte Nolin.

Photo: Hayf Photography

A powerful portrait

Charlotte has survived transphobic violence, homelessness, and drug and alcohol addiction. Today — at 73 — she is a grandmother, Sweat Lodge Keeper, Knowledge Keeper, Sundancer and Pipe Carrier. She is also the subject of a powerful portrait painted by Métis artist JD Hawk, recently acquired by the Canadian Museum of History.

Hawk says, “I call it my Mona Lisa painting, just because it’s just a slight smile. Just showing off the energy. The broad shoulders show a strong, strong person. Very approachable, with the lights and shadows that I used on her face. The strong working hands that she’s had all her life. And the delicateness of her personality just with the eagle feather fan.”

Kristine McCorkell is the Curator of Indigenous Art at the Canadian Museum of History. They describe the painting as a challenge and an invitation: “Charlotte is calling us into the painting and asking us to reflect on some of those taboos that have been ingrained in us.”

Stands Strong Eagle Woman: A Two-Spirit Grandmother, by JD Hawk.

Canadian Museum of History

Indigiqueer/Two-Spirit representation

McCorkell identifies as Two-Spirit and is Kanien:kehá’ka from Six Nations of the Grand River. They say, “It’s still very hard to talk about sexuality and sexual identity in museum spaces. For those of us like me, growing up, museums stayed away from it for a very long time, and I didn’t see myself represented in those spaces.”

McCorkell adds, “If I saw this as a young person when I was trying to figure out my own identity as a teenager, it would have answered a lot of questions. It would have pointed me in a direction of — we do belong, we are allowed to be here. It would be a radical shift for someone who’s really questioning their identity to walk in and see that representation, because we don’t see it in our everyday life.”

Nolin is an important example and leader for queer and Two-Spirit Indigenous youth. McCorkell says, “Charlotte took these teachings and started giving them back to the youth, started inviting these queer people who maybe did not have a safe ceremonial space to go to, to allow them to do that, and she holds space for them.”

A Two-Spirit leader

The term “Two-Spirit” — which Nolin embraces — refers to the wide range of gender and sexual identities that exist in many Indigenous cultures. The phrase was coined in 1990 in Manitoba, at the third annual North American Native Gay & Lesbian Gathering, but the Two-Spirit identity has existed since time immemorial.

Before North America was colonized, many Indigenous nations recognized a range of genders and sexualities. In many cases, Two-Spirit individuals were revered and considered gifted. They were healers and caretakers, had relationships, raised children, and participated as valued members of their communities.

Nolin says, “I’m a Sundance Chief. And in that role, I lead my people in ceremony. And last year, we held the first Two-Spirit Sundance on Turtle Island, and we had about 400 people that attended. To describe it in words, it’s just too difficult — the feeling of hope, the feeling of respect, the feeling of acceptance — it just overwhelmed us for four days.”

Artists JD Hawk, Jason Sikoak and Leticia Spence (left to right). Hawk’s portraits of Métis community members and leaders recognize the vibrant diversity of contemporary Métis life and culture.

The Canadian Press / David Lipnowski

Decolonizing gender and sexuality

McCorkell notes that Indigenous experiences and histories of sexuality and gender are very different from European colonial norms. They say, “Most of our communities understood gender and sexual diversity very differently. We didn’t have gender, at least in my language. That was something that came after colonization.”

Now, they say, “we have to seek out our own communities — queer Indigenous people, Two-Spirit, Indigiqueer, queer, however we identify. We know that we don’t necessarily fit in with all our communities right now, and we seek each other out in these contemporary spaces.”

Nolin says:

“You know, when I think back at my life and how I was so small growing up because society made me small, and then one day I emerged — just like a butterfly emerges from a cocoon. And I spread my wings. And I said, ‘this is who I am.’”

The portrait of Charlotte Nolin is on display in Gallery 3 of the Canadian History Hall.

Listen to Charlotte’s episode of Artifactuality to hear more about her story, the importance of recognizing Two-Spirit traditions and history, and the role museums can play in recognizing gender diversity.

Steve McCullough

Dr. Steve McCullough is the Digital Content Strategist at the Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum. His work in digital storytelling involves compassionate and evidence-based efforts to address history, meaning and identity in our fragmented and polarizing, but also vibrant and interconnected, online environment.