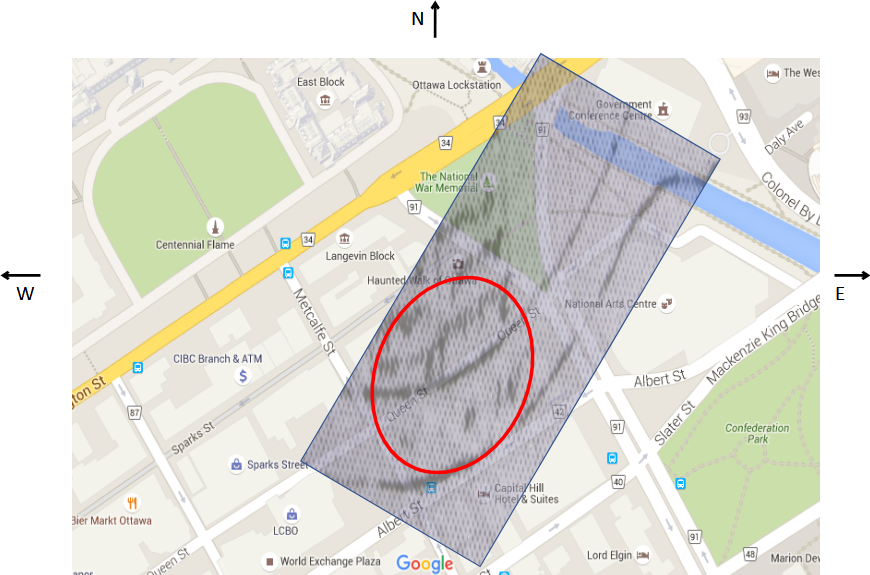

Barrack Hill Cemetery plan (red oval) overlaid onto map of downtown Ottawa

By looking at it today, you would never know that part of downtown Ottawa was built on the first settlers’ cemetery of Bytown, the Barrack Hill Cemetery (c. 1827–1845). After the discovery of human remains on Queen Street during light rail transit-related construction in 2013, removal of the remnants of the cemetery began in 2014. Another discovery of human skeletons in 2015 beneath the parking lot of 62 Sparks Street led to more excavations in 2016. Though the individuals found during these archaeological seasons have since been reburied at Beechwood Cemetery, I am continuing to work on the information they have revealed.

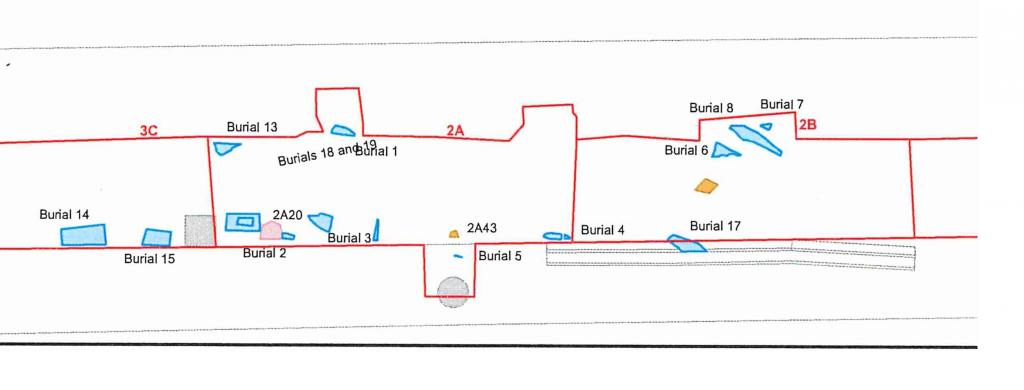

Excavations on Queen Street, 2014

Excavations of the parking lot behind 62 Sparks Street, 2016

Mitochondrial DNA analysis

My current research focuses on using DNA analysis to unlock new information held in the remains of the Barrack Hill Cemetery population. Working with the McMaster Ancient DNA Centre, mitochondrial DNA sequencing was successfully completed on 14 individuals found during the 2014 field season, with more testing to be carried out shortly on the remains from the 2016 field season.

Mitochondrial DNA, passed down from mother to child, is a tool used by researchers to trace direct descendants through many generations of the mother’s line. Our results so far have yielded population-level data and confirmed that those buried in the Barrack Hill Cemetery were from the European haplogroups H, U, J and K.

A haplogroup is a population group with a common genetic ancestor, which gives us an idea of their geographic origin.

Mitochondrial DNA results for 2014 burials

| Burials 2014- | Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup result |

| 1 | H |

| 3 | U5a2c1 |

| 4 | H3+152 |

| 6 | H4a1a4a |

| 7 | J1c3b |

| 9 | H5a1 |

| 10 | U5b1f1a |

| 11 | K1a4a1c |

| 13 | H31a |

| 14 | H5a1a1d |

| 15 | J1c3b |

| 16 | H5a1 |

| 17 | H1c1 |

| 18 | H1e1a8 |

There is a diversity of subclades, or subgroups (the subsequent numbers and letters), for each haplogroup, although there are two cases in which the population level DNA signatures are identical. Burials 2014-7 and 2014-15 are both from the group J1c3b, the only J mtDNA haplogroup in the series. These individuals were found in two different areas of the cemetery with nothing to indicate they were related.

Queen Street site plan of three of the excavation areas. Burials 7 and 15 are indicated by arrows (Mortimer, 2014).

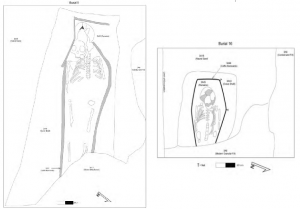

Burial, 9 and 16, field drawing (Mortimer, 2014)

We found that burials 2014-9 and 2014-16 not only share the mtDNA haplogroup H5a1, but they were also excavated from the same grave shaft. This was one of only two stacked burials encountered during two seasons of excavations at the site. Numbered in order of discovery, burial 2014-9 was found above 2014-16, with a layer of dirt separating the two coffins. Anthropological analysis of the skeletons indicates that the graves were those of children between the ages of 3 and 6 years old at death. The child in the bottom coffin, and thus the first interred, was burial 2014-16, who was found to be slightly older than the child of burial 2014-9.

Who might these children be?

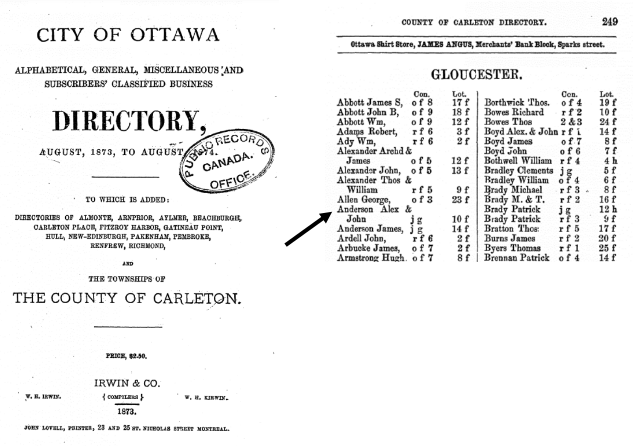

There is an incomplete set of burial records from the time when the Barrack Hill Cemetery was in use. I searched those records and identified two individuals in the Presbyterian registry with the proper ages at death and sequence of burial similar to what we see in the excavated remains. These were two children born to Alexander Anderson (1808–1886) and Margaret Whillans (1811–1882) of Gloucester. John Anderson died at age 5, on July 3, 1841. Barbara Anderson died at age 3, on July 7, 1841. Given the order of death, the fact that the children died days apart, and the identified age ranges for each, John may have been the child in Burial 16, while Barbara may have been the child in Burial 9.

City of Ottawa Directory 1873–1874 showing the children’s father, Alexander, and one of his remaining children, John, living in Gloucester. This John was born after his older brother, John Alexander, had died

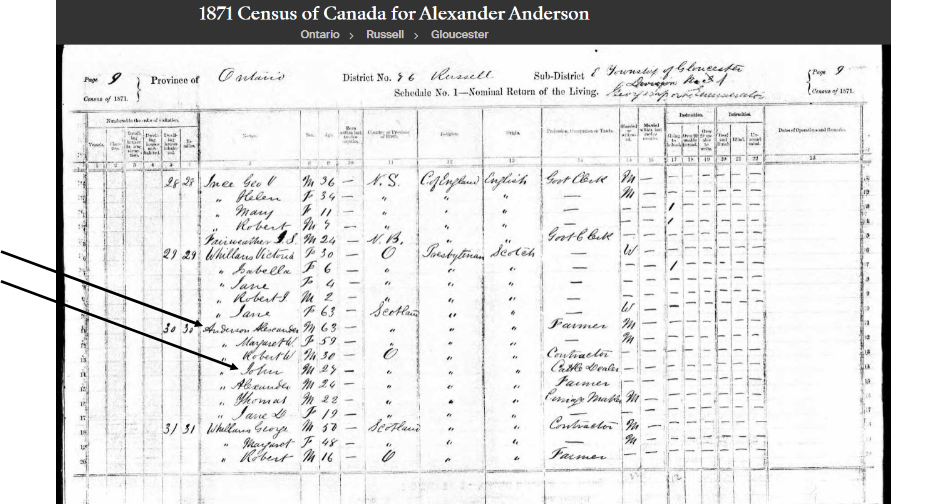

1871 census showing the living family members of Alexander Anderson including his son, John, whose age verifies he was born after his older brother, John Alexander, died in 1841 (Library and Archives Canada).

What are the next steps?

I have asked the DNA lab at McMaster University to compare the results of burial 2014-9 and 2014-16 to see if the children had the same parents. This will tell us whether or not burials 2014-9 and 2014-16 were siblings. If the lab determines that these children were siblings, the next step to identify if they are indeed John and Barbara would be to find a living relative from their mother, Margaret’s, female line. I am currently conducting genealogical research to identify if such a person exists. If a descendant can be identified, further DNA analysis could be attempted to allow us to know for sure if these little ones are the Anderson children, becoming the first positive identification of individuals buried in the Barrack Hill Cemetery.

As I continue to work on the individuals left behind in Barrack Hill Cemetery, their skeletal remains are providing a glimpse into the lives of the working-class men, women and children who built a town that became our nation’s capital. Soon, you will be able to read their stories in a book that is being written.

References and further information

- CBC News, “19th-century funeral held for remains found beneath parking lot,” October 7, 2019.

- City of Ottawa Directory 1873-74. Retrieved from Library and Archives Canada.

- Library and Archives Canada 1871 Census data. Retrieved from Library and Archives Canada.

- Mortimer, B (2014). Burial Site Investigation & Stage 4 Mitigation at the Barrack Hill Cemetery (BiFw-171) Final Report.

Janet Young

Dr. Janet Young is the Curator of Physical Anthropology at the Canadian Museum of History. Her research interests include biomechanical and pathological changes in the human skeleton as they relate to activity patterns and general health outcomes of past and present populations. Her expertise includes museum studies, repatriation, forensics, bioarchaeology, burial practices, and disability.