The Official Languages Act, adopted and coming into effect in 1969, was a milestone in Canadian history, but it did not put an end to debates that had endured for more than a century. It is one thing to put a piece of legislation on the books, but quite another to have it embraced by hearts and minds.

The first few years were turbulent. Many Canadians welcomed the change enthusiastically. Anglophones set out to learn French. The “two solitudes” drew closer in daily life, culture, politics. The federal government, led by Pierre Elliott Trudeau since 1968, established “French Power” — considerably increasing the number of important positions occupied by Francophones.

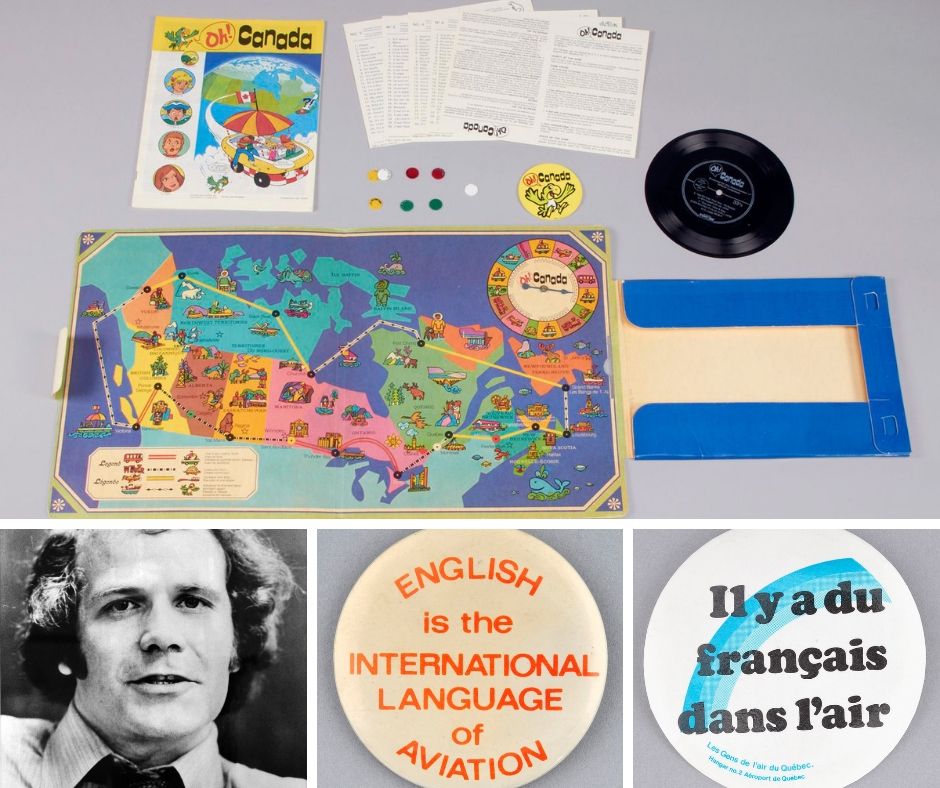

The first Commissioner of Official Languages, heading up an organization created in 1970 to ensure that the Act was followed, was Keith Spicer — a young and colourful journalist who promoted bilingualism with humour and energy. To the Commission we owe a board game, issued in 1974, called Oh! Canada. The game would be highly successful — two million copies were produced — and invited players to travel the country along a route riddled with pitfalls.

The game both reflected and stimulated enthusiasm for bilingualism among certain Canadian youth. In a similar vein, in 1977, an organization called Canadian Parents for French was born, created by Anglophone parents wanting to enrich their children’s personalities and futures by encouraging the teaching of French, and teaching in French.

Up: Oh! Canada game. Canadian Museum of History, 2009.71.1226. Down (left to right): Keith Spicer, first Commissioner of Official Languages (1970-1977). Photo: Courtesy of the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages; buttons linked to the Gens de l’air crisis in 1975–1976. Canadian Museum of History, 2011.185.5 and 2011.21.207

But this progress was often met with resistance. Many other Canadians viewed the policy on official languages with distrust. In Quebec, supporters of nationalism and independence suspected that this might be a ruse to make Quebec bilingual, and to make Franco-Quebecers believe that the country had suddenly become bilingual from sea to sea.

Among Anglophone Canadians, on the other hand, the Act was often confused with an obligation to learn French on pain of demotion. “They are forcing French on us!” was heard in both private and public. A pamphleteer had some success in 1977 with a work bearing the rather alarming title, Bilingual Today, French Tomorrow.

Mutual lack of understanding came to a head with the Gens de l’air crisis in 1975–1976. A directive from the Department of Transport had allowed, for the first time, the limited use of French in certain control towers in Quebec. This led to a general outcry among Anglophone pilots, who asserted that English should be the only language used in aviation, even between Francophones in the cockpit, for presumed reasons of security. Humiliated, Francophone pilots responded by creating the Association des Gens de l’air. The crisis was winding down in 1976, but not before the aviation sector was disrupted by a week of strikes, on the eve of the Summer Olympics in Montréal.

Enthusiasm, hostility and many shades of grey lay between these two extremes. The first few years following passage of the Official Languages Act would leave no Canadian indifferent.

See also Part 1 – The Official Languages Act: A Difficult Birth (1962–1969)

Dr. Xavier Gélinas is Curator, Political History at the Canadian Museum of History.