Although Paul Martin was Canada’s Prime Minister for a relatively brief period, from December 2003 to February 2006, he had a major impact on the political and economic history of the country.

Born in Windsor, Ontario, in 1938, he was long viewed as the son of the “other” Paul Martin, a political heavyweight. Paul Martin, Sr. (1903–1992) was a federal Liberal Party MP for 35 years before being named a senator, then High Commissioner (ambassador) to London. In addition to being a high-ranking minister, he also campaigned to become party leader on three separate occasions.

Button for Paul Martin, Sr.’s leadership run for the Liberal Party of Canada, 1958.

Gift of the Honourable Serge Joyal. Canadian Museum of History, 2012.17.657

Promotional folder for Paul Martin, Sr.’s campaign for leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada, 1968. Inscription: “Paul Martin speaks for Canada.”

Gift of Christopher McKillop. Canadian Museum of History, 2020.107.2

“Our” Paul Martin accordingly had to differentiate himself from his famous father. This no doubt explains his belated entry into politics. After studying law, he switched to business, joining the Power Corporation conglomerate in 1966. He was particularly interested in a specific branch of the company: the navigation corporation Canada Steamship Lines, which had roots dating back to the 19th century. He became president in 1973, then purchased the corporation in 1981, at the age of 43. It looked as though Martin’s future was all mapped out — with a focus on maritime transport, and expansion of his company.

The Canada Steamship Lines cruise ship St. Lawrence, before 1965.

Gift of Manon Guilbert. Canadian Museum of History, 1998.92.4

The Canada Steamship Lines ship Edmonton, before 1961.

Canadian War Museum, Photographic archives, 19810448-050

After business: politics

Ultimately, political fervour would outstrip his taste for business, and he threw his hat into the ring during the 1988 federal election. Elected to the House of Commons as Liberal MP for LaSalle-Émard — a Montréal riding — he initially sat in opposition to the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney.

In 1990, following the departure of Liberal leader John Turner, Martin set his sights on becoming Turner’s successor, despite having scant political experience. His main opponents were Jean Chrétien, a key political figure since the early 1960s, and spirited MP Sheila Copps. The result: an honourable but distant second place, with 25 percent support. Martin accordingly became Chrétien’s loyal right-hand man — first in opposition, then in power — a position that was uncomfortable for both men. “Jean Chrétien and I had a personal relationship that ran the gamut from cool to non-existent,” Martin would say. For better or for worse, that relationship would persist into the early 2000s.

Restoring public finances

After the 1993 federal election, won by the Liberals, Chrétien named his former rival Finance Minister. Martin would occupy that post for nearly 10 years, making him the longest-serving Finance Minister since the First World War. His lengthy tenure made it possible for him to have an enduring impact on the Canadian economy.

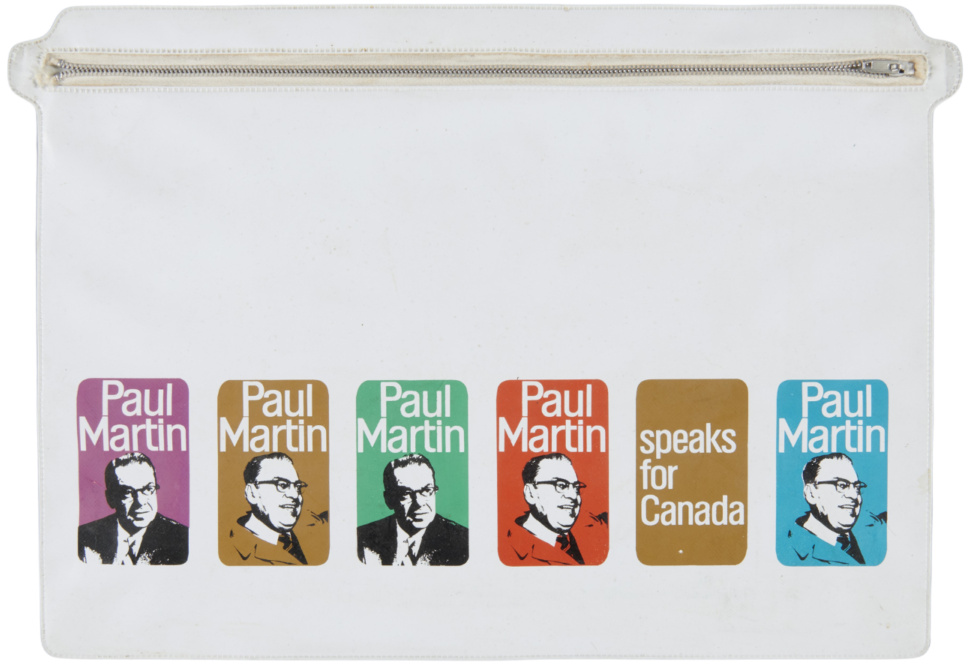

When he took up his post, the country was running a worrisome deficit. Interest payments on the debt ate up more than a third of the federal budget! In the fall of 1994, the new Minister published two policy papers — the “grey book” and the “purple book” — detailing his plans for the future. Decisive action was needed. In January 1995, for example, the Wall Street Journal described our dollar as the “northern peso,” and called Canada an “honorary member of the Third World.”

The following month, the ratings agency Moody’s placed the Canadian government “under review,” due to its high level of debt in relation to gross domestic product. Martin needed, in his own words, to eradicate the deficit, “come hell or high water.” That expression would become so enshrined in popular memory — a sign of his convictions — that Martin would use it as the title of his autobiography. He pulled no punches, saying, “We are in hock up to our eyeballs. That can’t be sustained.”

The “grey book” and the “purple book,” the two policy papers from 1994 in which Paul Martin laid out his vision for the economy and government finances.

Photo: Steven Darby, Canadian Museum of History, Library, HC 113 C73 1994 and HC 113 N48 1994. IMG2023-0267-001

Martin’s budget on February 27, 1995, proposed a radical response. His tone was unequivocal: “Our view is straightforward. If government doesn’t need to run something, it shouldn’t. And in the future, it won’t.”

His actions reflected his words. Departmental budgets were cut by nearly 20 percent, or $25 billion over three years — $45 billion in today’s dollars. Military bases, employment insurance payments, international aid, grants to businesses . . . there wasn’t a single budget item that escaped. Forty-five thousand civil servants lost their jobs over a three-year period. The government sold off its shares in Petro-Canada, and privatized Canadian National Railways. And transfer payments to the provinces were cut by a quarter between 1995 and 1998.

It all came as a major shock, and such a sustained effort would obviously arouse discontent. The provinces protested reductions in their transfer payments, which were forcing them to make difficult choices: reduce public services, transfer responsibilities to municipalities, or take on the expenses themselves, chipping away at their own bottom lines. Social and environmental lobby groups bemoaned reduced government support to groups already operating on a shoestring.

The uneasiness travelled all the way into the heart of government and the Liberal Party. Although Prime Minister Chrétien generally supported his Finance Minister, his own social conscience was being tested. Other colleagues with a progressive bent, such as Minister Sheila Copps, were sometimes openly antagonistic; in their opinion, the party was moving away from the centrist and humanist traditions espoused by Lester B. Pearson and Pierre Elliott Trudeau from the 1960s through the 1980s.

Martin held firm, however, and in 1998, the Canadian budget was balanced — for the first time in three decades. It would remain that way in the years ahead, launching a “virtuous cycle”: lower interest rates from creditors, the availability of funds for new programs (such as the Canada Child Benefit), lower taxes, economic growth, less unemployment, and the beginning of repayment of the accumulated debt.

Finally Prime Minister

In 2003, the announcement of Chrétien’s retirement opened the door to a run at leadership of the Liberal Party. Martin won handily with 93 percent of the delegates’ vote, attesting to his political, intellectual and personal influence. He had won over the Liberal Party since his active entry into politics 15 years earlier. The future looked bright for the man who was sworn in as Prime Minister on December 12, 2003.

However, unforeseen obstacles would put the brakes on Martin’s momentum. Years of rivalry between himself and Chrétien had left wounds that were slow to heal within the Liberal caucus. In addition, although brimming with ideas and projects, Martin did not always know how to prioritize them, or communicate them clearly to people across Canada. His sincere belief in widespread consultation earned him the nickname “Mr. Dithers” by the magazine The Economist.

Despite disappointments and mistakes along the way, one achievement would remain a bright spot for Prime Minister Martin: the Kelowna Accord.

The agreement — signed in November 2005 following 18 months of discussion between the federal government, the provinces, and Indigenous associations — pointed a way forward in providing more effective socioeconomic support to Canada’s Indigenous Peoples. At the opening ceremonies in November 2005, as a vote of confidence, the Manitoba Métis Federation presented the Prime Minister with a superb buckskin jacket with beaded fringe — carefully created by Winnipeg artisans Jenny Meyer and her daughter Jennine Krauchi. The Canadian Museum of History is honoured that Martin later donated the jacket to the national collection.

Jacket presented to Prime Minister Paul Martin during the Kelowna conference on Indigenous issues, November 2005.

Gift of the Right Honourable Paul Martin. Canadian Museum of History, 2011.118.1. IMG2014-0017-0003.

Prime Minister Paul Martin with Phil Fontaine, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, during the Kelowna conference on Indigenous issues, November 2005.

Photo: Fred Cattroll. Canadian Museum of History, Photographic Archives, IMG2012-0039-2055.

Paul Martin and our Museums

There is another important link between Martin and our institution — particularly the Canadian War Museum. The Prime Minister was the guest of honour at the opening ceremonies for the new Museum on May 8, 2005. His moving words reflected the ambitions of the Museum: “It is Canada’s odyssey — fraught with dangers and challenges, with sacrifice and sorrow, with triumph and tragedy. Within these trench-like walls, familiar and strangely comforting, time is suspended. We live for a moment within those who experienced war.”

Unveiling of the new Canadian War Museum, May 8, 2005. Left to right: Claudette Roy, Chair of the Board of the Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation; Liza Frulla, Minister of Canadian Heritage; Prime Minister Paul Martin; and his wife, Sheila Ann Martin.

Photo: Steven Darby. Canadian War Museum, Photographic Archives, CWM2012-0006-0025-Dm

Prime Minister Paul Martin, in his official address at the inauguration of the new Canadian War Museum, May 8, 2005.

Photo: Steven Darby. Canadian War Museum, Photographic Archives, CWM2012-0006-0038-Dm

The unexpected: sponsorships

Despite a commendable track record of successes and projects, a shadow was ultimately cast over Martin’s 26 months in power, by an affair that did not concern him directly: the Sponsorship Scandal.

Following the 1995 Quebec Referendum on sovereignty, the Canadian government created a major initiative aimed at stimulating closer ties between Quebec’s people and federalism. However, the initiative was marked by serious irregularities, brought to light through an unfortunate coincidence shortly after Prime Minister Martin took office.

During his time as Finance Minister, Martin had played no role whatsoever in the program, and knew nothing of its issues, as was confirmed in later enquiries. When it came to public opinion, however, the damning report from the Auditor General in 2004, followed by that of the Gomery Commission in 2005 — ordered by Martin himself to get to the bottom of things — could only damage the image of the Liberal Party, and thus its new leader.

Hobbled by this affair, Martin managed a minority win in the June 2004 elections, but suffered a narrow defeat at the polls on January 23, 2006, at the hands of the Conservative Party, then led by Stephen Harper. That same night, before supporters in LaSalle-Émard who had just re-elected him for a sixth consecutive mandate, he bowed out as party leader.

Since leaving the political scene, Martin has devoted his energy to two causes that have always been close to his heart: Economic development in Africa, and improving the economic, political and educational well-being of Indigenous populations in Canada.

Campaign poster for Paul Martin’s run for leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada, 2003.

Gift of the Honourable Serge Joyal. Canadian Museum of History, Document Archives, 2012-H0040_133_001

Election button for the Liberal Party of Canada, led by Paul Martin, 2004.

Gift of Alain Lavigne. Canadian Museum of History, 2018.305.23. IMG2023-0097-0107

Xavier Gélinas

Xavier Gélinas has been Curator, Political History, since 2002. He is responsible for initiating the Museum’s Canadian political history collection, which he continues to expand through additional objects and documents.

Read full bio of Xavier Gélinas