Joe Clark’s term as Canada’s 16th Prime Minister was brief, lasting 273 days in 1979–1980. But those nine months represent only a key moment in the long career of this proud Albertan, who left his mark as a party activist, member of Parliament and federal minister.

Coming of age in Alberta

Charles Joseph Clark was born on June 5, 1939, in High River, a small town in southwestern Alberta. High River is known for its wide-open spaces, vast skies, and prosperous farmers. The Clark family was involved in journalism: Clark’s father, Charles, was editor-in-chief of the weekly High River Times, founded by Clark’s grandfather in 1905.

The Second World War broke out shortly after Clark’s birth. His hometown gained a certain geopolitical importance when a British Commonwealth Air Training Plan school was established there, training no fewer than 4,000 pilots up until 1944.

Joe Clark was tempted to follow in his family’s journalistic footsteps, but he was also fascinated by politics, and straddled both worlds for a number of years. At the University of Alberta, he earned a bachelor’s degree in history, while editing the magazine The Gateway. He went on to study law at Dalhousie University in Halifax, then at the University of British Columbia, but his heart wasn’t in it.

Clark preferred to devote his time to activism, and accordingly presided over the Progressive Conservative Student Federation of Canada. He then re-enrolled at his first alma mater, the University of Alberta, where he earned a master’s degree in political science. This same university remained a constant in his life. After earning his two degrees, he became a teaching assistant there in the 1960s. In 1985, the University presented him with an honorary doctorate. He came full circle in the 1990s when he was made an associate professor in the Faculty of Arts.

High River No. 5 E.F.T.S., April 23, watercolour by Sergeant Thomas S. Hodgson, April 23, 1944. Clark spent the first 18 years of his life in High River, Alberta.

Gift of Cathy Good. Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, Canadian War Museum, CWM 19970044-034, IRN 1032747.

Rows of de Havilland Tiger Moths at the High River aircrew training school, 1943.

George Metcalf Archival Collection, Canadian War Museum, CWM 19740387-003, IRN 3124850.

University of Alberta tankard, 1964. Joe Clark studied there, taught there and received an honorary doctorate from there.

Gift of Auguste and Paula Vachon. Canadian Museum of History, 2009.4.118, IMG2012-0252-0161.

Electoral politics did not yet interest Clark, although the role of political advisor did. After Robert Stanfield was made leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada in 1967, Clark became his speechwriter and moved to Ottawa. Clark enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with Stanfield, a level-headed man who, like Clark, had come from a remote town (he was Nova Scotian), and who wanted to modernize his party without abandoning its traditions. These years in Stanfield’s shadow were formative ones. Clark learned the inner workings of the Ottawa political scene, and began assiduously studying French — an essential asset, in his opinion, to any national future.

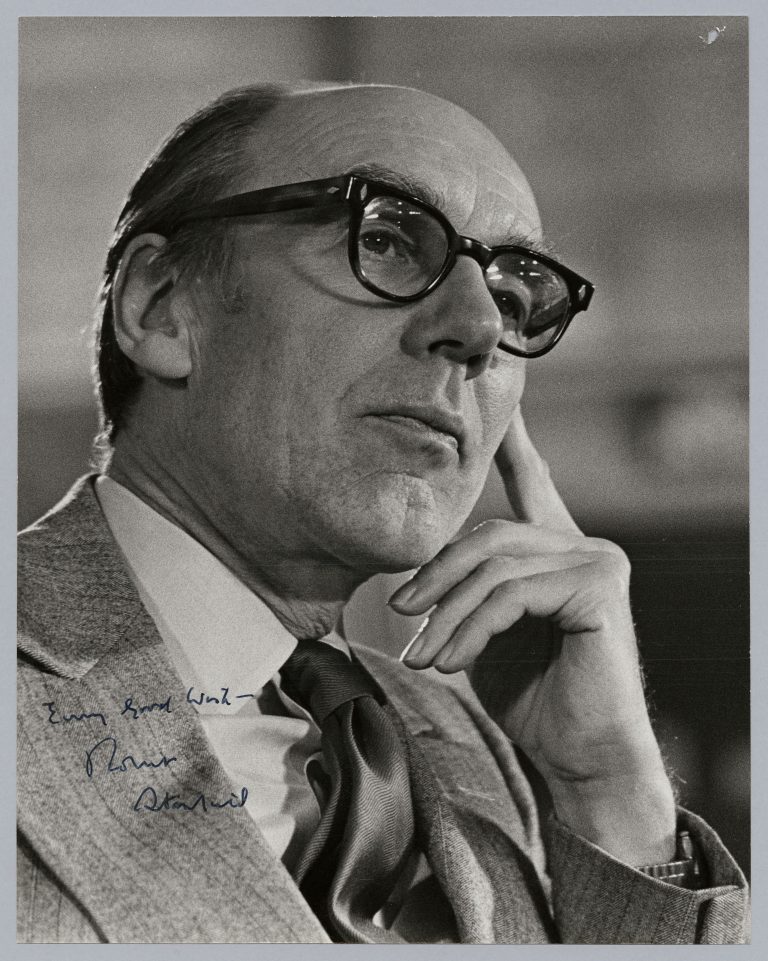

Robert Stanfield, leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada (1967–1976), and Joe Clark’s mentor. Signed photograph, 1970s.

Gift of David Daubney. Canadian Museum of History, Photographic Archives, 2022-H0005_5, IRN 5767078

Parliamentary beginnings (1972–1976)

In 1972, during the federal election, Clark felt ready to toss his hat into the ring. He stood as a candidate in Rocky Mountain, Alberta, winning the first of eight electoral victories. He learned the ropes as a member of the Opposition, given that Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s Liberal Party had won a new term. Clark’s first months in Parliament also brought personal happiness: he succumbed to the charms of Maureen McTeer, a dynamic student who was passionate about political action. The couple soon married, and their daughter, Catherine, would become a well-known media figure.

When his party’s leader, Stanfield, announced his resignation, Clark decided to run as his successor at the 1976 leadership convention. To everyone’s surprise, he won. One of his opponents was a lawyer from Montréal: like Clark, born in 1939 and active in conservative circles since his early twenties — a certain Brian Mulroney. Their paths would one day cross again.

Joe Clark’s rapid rise to leadership came with some challenges. Although he had been engaged in politics for years, he was not well known by the general public, nor even within his own party or by his own caucus. The day after his victory, the headline on the front page of the Toronto Star read, “Joe Who?” Clark’s relative youth (he was only 36 years old) was also something of a handicap among more experienced political hands and journalists. In addition, he wasn’t particularly confident or self-assured in public, in sharp contrast with the charisma of his rival, Pierre Trudeau. In the ensuing years, Clark would work flat out to gain greater recognition and credibility.

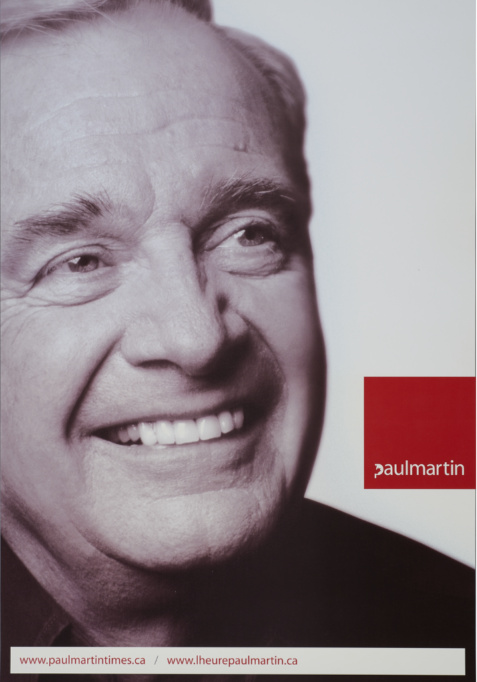

Campaign button for Joe Clark as leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada, 1976.

Gift of Nancy Ruth, O.C. Canadian Museum of History, 2009.7.36, IMG2010-0082-0059.

A “Red Tory”

But what exactly were his views? Joe Clark was a so-called “Red Tory”: a left-leaning Conservative. This is often how people described politicians who were cautious on the economic front, but who also demonstrated openness on social issues, such as the advancement of women and cultural minorities. “Red Tories” like Clark also embraced bilingualism, and believed that the State could be a positive force in society. These convictions often placed Clark in an awkward position when it came to the more traditional Conservative base.

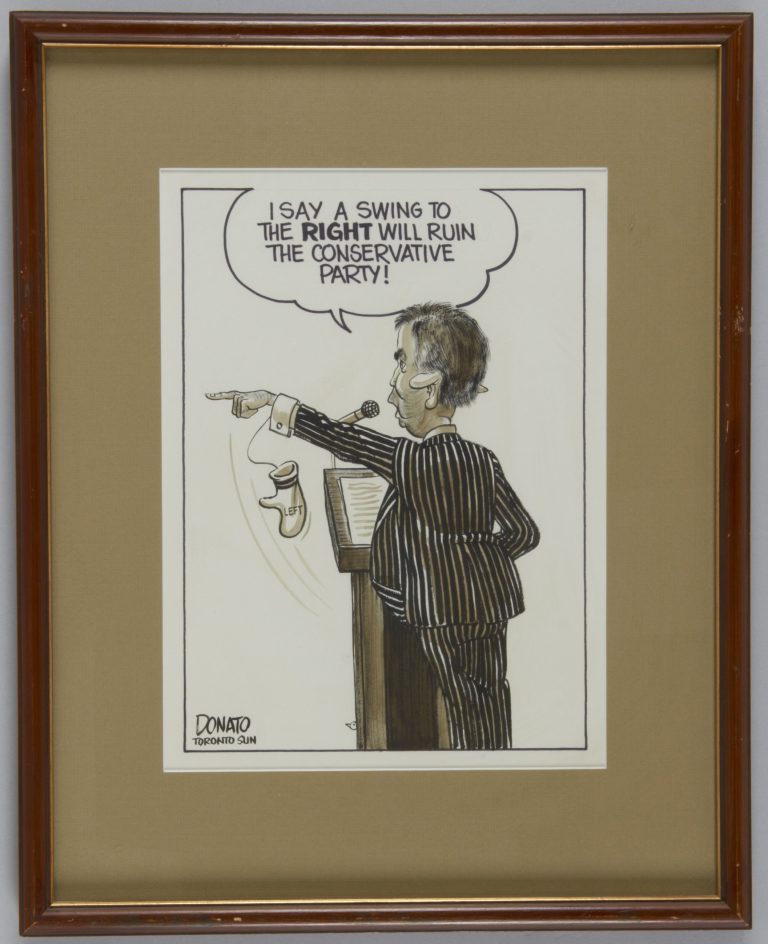

Political cartoon by Donato, “I say a swing to the right will ruin the Conservative Party!”, around 1983. The artist illustrated Joe Clark’s stance, which often ran contrary to the position of his political family. Courtesy of Andy Donato, Toronto Sun.

Gift of Jack Granatstein, O.C., PhD, FRSC. Canadian Museum of History, 2013.27.7, IMG2014-0084-0017.

Canada, a “community of communities”

At the same time, Joe Clark fully embraced his conservatism, by advocating for a central government that would not oversee and control every last thing. His first speech as prime minister, in 1979, made this crystal clear: “The nation is more than the central government.”

Clark was also open to the unique character of Quebec. More broadly, he celebrated the differences that, in his opinion, made Canada a great country. He summed up his pluralistic approach in a famous speech delivered at Toronto’s Empire Club in 1979:

“We are a nation that is too big for simple symbols. Our preoccupation with the symbol of a single national identity has, in my judgment, obscured the great wealth we have in several local identities which are rich in themselves and which are skilled in getting along with others. […] In an immense country, you live on a local scale. Governments make the nation work by recognizing that we are fundamentally a community of communities.”

This would be Clark’s guiding principle throughout his journey. In 1994, for example, he wrote:

“Part of the reason the ‘Canadian identity’ is hard to dramatize is that we are a nation of very strong local communities, each with a sure sense of its own identity. That can be divisive, if frustration prevails, whether in Quebec or Calgary or among the Crees. But it is also, everywhere, a source of pride and definition, which can reach outward as easily as it can turn inward. The challenge for Canada is to find ways to encourage citizens who are acutely proud of their own community to take an equal pride in the country.”

Prime Minister (1979–1980)

During the May 1979 federal election, Joe Clark defeated Pierre Trudeau. At the age of 39, he became the youngest prime minister in Canadian history. Clark could be justifiably proud, but his victory was hardly a walk in the park. In fact, his party won only 136 seats — against 114 for the Liberals, 27 for the New Democratic Party and 5 for the Social Credit Party based in rural Quebec. It was thus a minority government, sentenced to caution and the forming of alliances on a case-by-case basis.

The Clark government settled in for good or ill. The ministers and MPs often betrayed their lack of experience as the party in power. There were blunders galore, although new and often daring initiatives also emerged. Several international briefs reflect this curious mix.

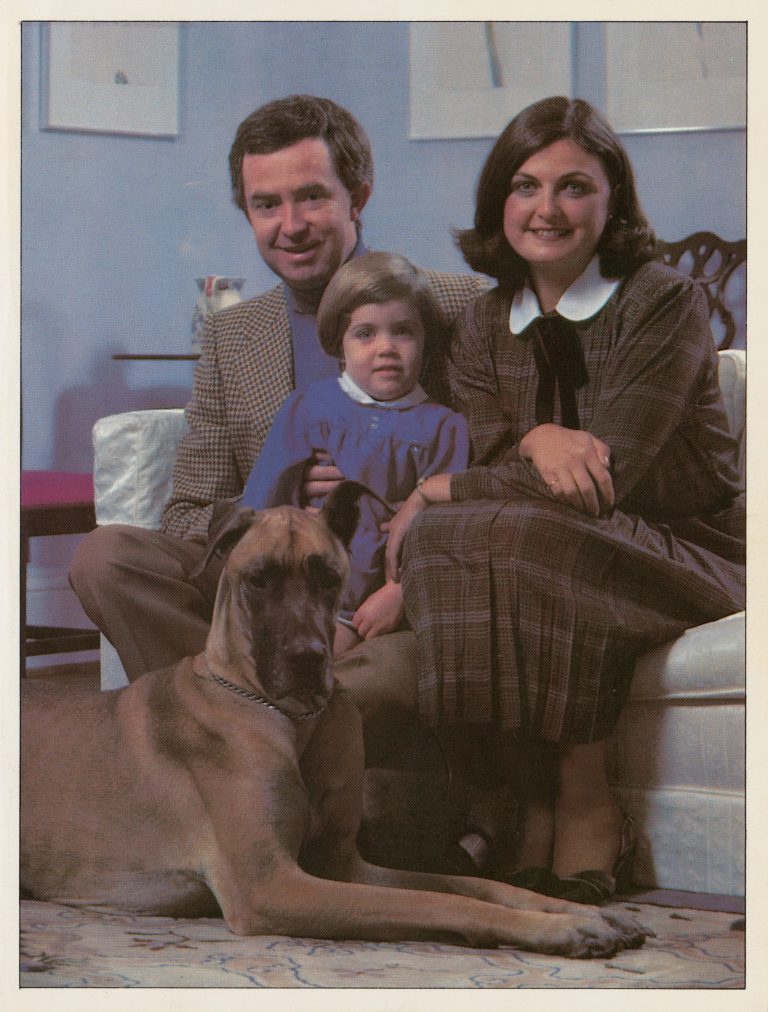

Christmas card from Joe Clark as Prime Minister of Canada, 1979. At his side: his wife, Maureen McTeer, their daughter, Catherine Clark, and their Great Dane, Taffy.

Gift of Alain Lavigne. Canadian Museum of History, Archives, 2023-H0001-60-001, IRN 5818562.

One of the Clark government’s masterstrokes occurred when the Canadian ambassador to Iran, Ken Taylor, was able to harbour and smuggle out six American diplomats who had escaped an attack on the U.S. Embassy in Tehran in November 1979. Clark and his Secretary of State for External Affairs, Flora MacDonald, gave their full support to this risky operation. It was also Clark’s government that decided to welcome an unprecedented number (50,000, soon to become 60,000) of Vietnamese refugees — the so-called “Boat People” — in a humanitarian action that was acclaimed worldwide.

By contrast, the Clark government suffered an unfortunate entanglement in its Middle East file. During the election campaign, in a gesture of openness towards Canada’s Jewish community and the Israeli government, the Progressive Conservative Party had promised that the Canadian Embassy in Israel would be moved from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Clark had not foreseen — although he probably should have — the outrage of the Arab-Muslim community, for whom Jerusalem is both a holy city and disputed territory. Following an international firestorm, the Prime Minister was forced to cancel the project, in a volte-face that damaged his reputation.

Joe Clark did not stay in power for long. His government was defeated during the tabling of its first budget, on December 13, 1979, by a narrow vote of 139 to 133. The Social Credit MPs, who felt slighted by Clark, chose to abstain. The die had been cast.

Back in opposition (1980–1984)

Joe Clark and his party thus returned to the polls. In the February 1980 election, the country restored Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals to power, with a majority win. It was a tough defeat. Clark was forced to cross the floor in the Commons, returning to the opposition benches.

Discord was also rising within his party. At the Progressive Conservative convention in early 1983, Clark received the support of 67 per cent of members. This was nothing to sneeze at, but he wanted to establish his authority once and for all, spearheading a leadership convention for June 1983. He was now campaigning as his own successor. He faced off against a number of opponents, including Brian Mulroney, whom Clark had defeated seven years earlier. For convention attendees, Mulroney represented hope and something new. They chose Mulroney on the fourth and final ballot over Clark, who now returned to being a simple MP.

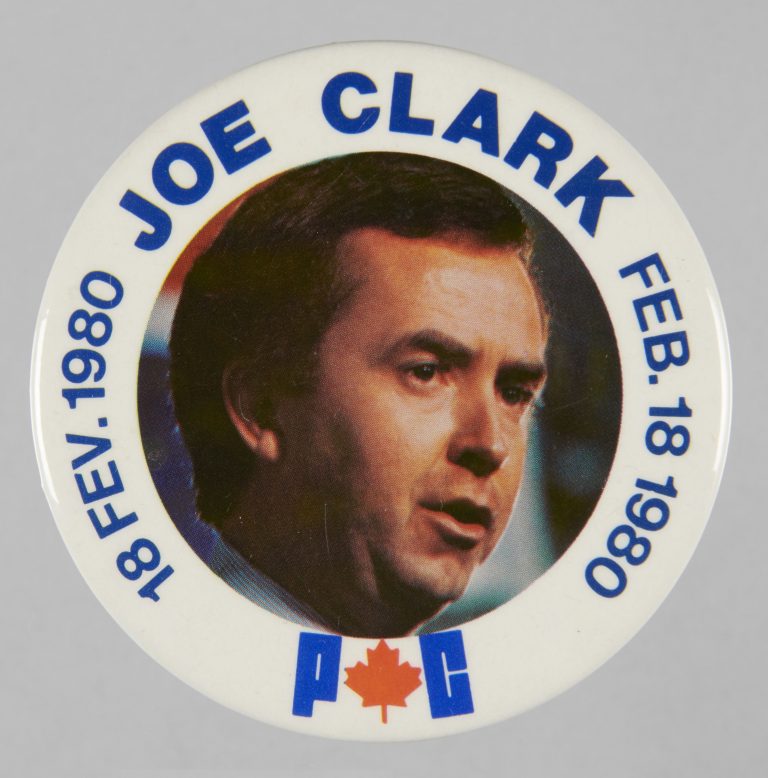

Button supporting Joe Clark and the Progressive Conservative Party for the 1980 federal elections.

Gift of David Daubney. Canadian Museum of History, 2019.178.18, IMG2022-0116-0057

Achieving new stature: External Affairs (1984–1991)

After two major setbacks (with the electorate in 1980, then within his own party), most public figures would have retreated to the private sector, fleeing the slings and arrows of politics. Joe Clark, however, did not throw in the towel. He bound up his wounds and rallied around his new leader.

In the 1984 elections, Clark was part of the “Blue Wave” that returned the Progressive Conservatives to power. The new Prime Minister magnanimously offered Clark the External Affairs portfolio. Mulroney valued Clark’s experience, integrity and dedication to public service. Their former rivalry gave way to mutual respect, and Joe Clark would later write:

“Mr. Mulroney and I had been fierce opponents, in two tough leadership campaigns. We agreed on fundamental issues about the country but, in personal terms, were probably more different from one another than Jean Chrétien is from Paul Martin. Yet, through eight active and contentious years in office, we put our differences aside, and worked together. It was more than my being a gracious loser; he was a gracious winner.”

Joe Clark, Secretary of State for External Affairs. Signed photograph, June 14, 1989.

Gift of Grant Harper. Canadian Museum of History, Photographic Archives, IMG2023-0136-0006

At External Affairs, Mulroney set the political agenda and reserved some files for himself. For the rest, however, Joe Clark had carte blanche. This would be a productive approach. Observers were impressed. Although the young party leader had appeared awkward — even clumsy — during the 1970s, the minister of the 1980s, who had weathered numerous trials, inspired confidence and respect.

The apartheid file reflects the effectiveness of the Clark-Mulroney partnership well. It was, first and foremost, the Prime Minister who had to convince the world’s major leaders, including his friends Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, to support liberalization of the situation in South Africa. But it was Clark who tirelessly maintained contact with each and every one, striving to attain consensus, thanks to his trademark ability to listen.

Canadian diplomacy accordingly appeared active on all fronts. In Africa, particularly in Ethiopia, Clark urged action from federal authorities — and, by extension, the Canadian people — by coordinating and doubling private donations to help alleviate widespread famine. It was also under the aegis of Minister Clark that Canada joined the Organization of American States, ending decades of half-hearted links with Latin America and the Caribbean. Finally, Joe Clark played both host and facilitator during a crucial international conference called “Open Skies,” held in Ottawa in 1990, which prepared the world for a reunified Germany and a future free of the Cold War.

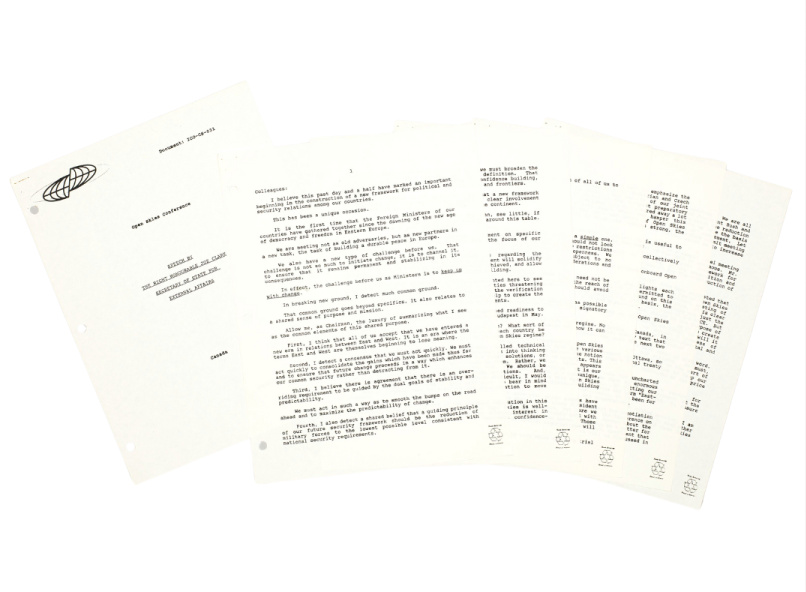

Joe Clark’s speech at the Open Skies Conference in Ottawa, February 13, 1990.

Gift of Lieutenant-Colonel Jacques Bailliu. Photo: Susan Ross. Canadian War Museum, Photographic Archives, 20110142-003_13 Feb 1990, IRN 5827269.

Joe Clark with six other former leaders of External Affairs, sometime between 1996 and 2000. From left to right: Mitchell Sharp, Allan MacEachen, Flora MacDonald, Joe Clark, Barbara McDougall, Lloyd Axworthy and Perrin Beatty.

Gift of the Mitchell Sharp Estate. Canadian Museum of History, 2005.32.64, IMG2008-0060-0025.

Minister Responsible for Constitutional Affairs (1991–1993)

In 1991, the Mulroney government was confronted with a national unity crisis. The Meech Lake Accord, aimed at settling the position of Quebec within Canada, had failed the previous year. Discontent was also brewing in the West, and among Indigenous nations. Almost everywhere there were acute regional, linguistic and identity-related tensions. How could these be appeased? Mulroney called upon his most reliable minister, Joe Clark. As Clark would later recall with a touch of irony: “My daughter, Catherine, best characterized the change, on the day I was ‘sworn out’ of External Affairs and ‘sworn in’ to my new portfolio. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘so long Paris, hello Moose Jaw.’”

Joe Clark buckled down to the task in his usual way, with determination and without fuss. After extensive consultations, in the fall of 1991, he presented a draft solution under the title, Shaping Canada’s Future Together.

In Charlottetown in the summer of 1992 — during intense negotiations between provincial and territorial premiers, as well as four national Indigenous organizations — Minister Clark achieved consensus on a suite of reforms. The Charlottetown Accord was both ambitious and complex. Among other things, the Constitution would be amended to recognize Quebec’s “distinct society,” would enshrine “the inherent right of self-government” for Indigenous Peoples, and would transform the Senate into a “Triple E” chamber: “elected, equal and effective.”

By all appearances, Clark had accomplished the impossible — or almost — gaining the approval of all Canadian political authorities around a constitutional document. Moreover, the New Democratic Party and the Liberal Party of Canada expressed their support.

The ultimate test would come in the court of public opinion. A nationwide referendum was held on October 26, 1992. It was a heartbreaking defeat for Clark and for the government. The Accord was rejected by 55 per cent of the Canadian electorate, and 56 per cent of the Quebec electorate. Too generous to Quebec, and too decentralizing, according to many. Not enough for Quebec, according to others. The “No” forces defeated the compromise embodied in the Charlottetown Accord. In the wake of this verdict Joe Clark ended his term as both MP and minister. He did not stand for re-election in 1993.

Minister of Constitutional Affairs Joe Clark, during the First Nations Circle on the Constitution, in the Grand Hall at the Canadian Museum of History, October 31, 1991.

Photo: Steven Darby. Canadian Museum of History, Photographic Archives, IMG2016-0043-502.

The return (1998–2004)

After 1993, Joe Clark seemed to have permanently turned the political page. After having occupied the highest positions and experienced political highs and lows, he turned to writing, to teaching and to the role of advisor, both in Canada and abroad. He became, in essence, an elder statesman. The days of the contemptuous “Joe Who?” were now a distant memory.

But never say never in politics. In 1998, Clark was back in the harness again. His beloved Progressive Conservative Party was seeking a leader, following the departure of Jean Charest. Clark agreed to lead his fellow Conservatives in a final campaign. The “Blues” of the time had been weakened, several of its previous supporters having deserted it for other parties. Clark and his party won only 12 seats and 12 per cent of the vote during the 2000 election. The return of Joe Clark to centre stage would be short-lived. Disappointed by the merger of his party with the Canadian Alliance (the new name for the Reform Party), he left the House of Commons for good just before the 2004 election.

Although Joe Clark’s term as prime minister was brief, it is his entire career that matters. In 25 years of parliamentary service (9,051 days, to be precise), he left his mark on the Commons, “the principal place where the Canadian community can act together,” as he said in his farewell speech in the House in 2004. Beyond Parliament itself, he had served his country with determination:

“Canada is, literally, too good to lose, but we have to work at building and keeping it.”

Xavier Gélinas

Xavier Gélinas has been Curator, Political History, since 2002. He is responsible for initiating the Museum’s Canadian political history collection, which he continues to expand through additional objects and documents.

Read full bio of Xavier Gélinas