The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic was a collective shock to society. Its medical impacts included hospitalization, death, and enduring disability. But it also led to emotional, economic and political turmoil. The Museum worked throughout the pandemic to collect objects and stories. Our goal is to preserve the story of this time of crisis, the consequences of which continue to unfold.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. It had been declared a “public health emergency of international concern” almost two months earlier. But by early March it was clear that this new viral disease had become a serious, worldwide threat.

The public health emergency declaration ended May 5, 2023. The director-general of the World Health Organization said that this “does not mean COVID-19 is over as a global health threat.” As of late September 2024, when Canada’s federal government ended its pandemic surveillance program, 60,871 people in Canada had died of COVID-19.

Pandemic culture shock

In the early phase of the pandemic, rates of infection rose rapidly. Treatments for the disease were experimental. The sudden hospitalization of thousands of people threatened to overwhelm health care systems. For months, there were no effective tests, treatments or vaccines. The public health response relied on social distancing to prevent the spread of disease.

The onset of the pandemic was a time of uncertainty and fear. The social, economic and personal impacts of life-saving lockdowns were significant and unsettling.

Collecting the pandemic

Museum research and collections work is often a blend of carefully planned and spontaneous work. The Museum had already been strengthening its capacity to respond quickly when appropriate. Part of our purpose is to collect material about significant social, political and cultural moments in Canada. We have to be ready to act when events of clear significance happen.

Our research team soon realized that this was a moment to document. We knew that we lacked material from the 1918 flu pandemic, which had also been a deadly upheaval of worldwide importance. This was a concrete call to action. The challenge: how to collect and share stories that reflected the depth and diversity of pandemic experiences in Canada?

Our pandemic collection plan had three goals. We wanted to document:

- public policy responses,

- how people experienced the virus and social restrictions, and

- cultural and artistic responses to the pandemic.

Example of cloth mask distributed by UFCW Local 401 at the Cargill meat processing facility in High River, Alberta.

Canadian Museum of History, 2021.53.1

Collecting during the pandemic posed unique challenges. It was necessary, for instance, to consider the health and safety of our employees and the public. This meant taking protective measures related to the virus, of course. We also had to consider the physical and emotional risk of engaging with polarized social conflict.

It was clear that anti-vaccination flyers and other protest materials were important for telling the story of this time. But protests over masks and vaccines sometimes led to vandalism, harassment and assault. Our staff collected protest materials very cautiously, and — like everyone else — worked online more than usual.

As the pandemic unfolded, sayings such as “we’re all in this together” gave way to the idea of being “in the same storm, but in very different boats.” We tried to collect items reflecting the diversity of experiences in Canada, including those of BIPOC communities that suffered disproportionately from the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic affirmed the importance of coordinated “rapid response” collecting policies and practices. Ultimately, we are preparing to tell the complex story of the pandemic to audiences who may or may not have experienced it or even remember it.

Public health as history

The disease COVID-19 is caused by a new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. Because this disease was new (at least in humans), the world’s medical researchers had a lot to learn. They did so as quickly as possible. The world found itself paying rapt attention to every scientific twist and turn of the race for treatments and vaccines. The technical vocabulary of epidemiology — “zoonotic,” “R0,” and “fomites” — suddenly became part of everyday conversation.

Science started to crack the code of detecting and treating the virus. Various forms of COVID-19 tests quickly became familiar. Rapid testing was the first breakthrough in managing the threat posed by COVID-19. It meant we could move away from blanket lockdowns towards managing risk based on exposure. The Museum collected a representative rapid test to help preserve and tell the story of this turning point in the pandemic.

Rapid-response test kits were essential in responding to COVID-19.

Canadian Museum of History, IMG2023-0033-0010-Dm

Public servants and scientists

In the face of widespread risk, uncertainty and fear, normally unknown and unheralded public health officials became recognizable public figures. We got used to hearing regular updates about the latest research from public servants such as Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer.

Dr. Bonnie Henry, the provincial health officer for British Columbia, was one of these sudden celebrities. She was often praised for her calm, comforting demeanour. But she was also notable for her fashion sense. She was frequently seen wearing stylish Fluevog shoes.

In spring 2020, designer John Fluevog released a limited edition “Dr. Henry” model to celebrate, well, Dr. Henry. The Museum collected a pair of these shoes. They will help tell the story of the public servants who were essential to explaining the constantly changing world of coronavirus research.

John Fluevog’s “Dr. Henry” model.

Canadian Museum of History, IMG2023-0033-0010-Dm

Community responses

During the public health lockdowns, homemade signs popped up everywhere. Many thanked essential workers or tried to keep community spirits up. But the conditions created by the coronavirus affected various communities differently. We all went through the same pandemic, but we did not experience it in the same way.

The Museum collected a range of signs and posters from different communities. They reflect varied perspectives on the unfolding crisis.

Richard McIlroy, Mischa McIlroy and Tanya Krupilnicki with their lawn sign, August 18, 2021.

Canadian Museum of History, 2021.93

Read the blog article: “Signs of the COVID-19 Era: Collecting Pandemic History”

Food security

Issues related to food were widespread during the early months of the pandemic. Shortages of staples such as rice and flour were common. People everywhere seemingly became obsessed with baking bread. As research manager Laura Sanchini writes, “Bread-making also gave us something we could control, however small. Even when we felt powerless to control so many things around us, we could control our sourdough.”

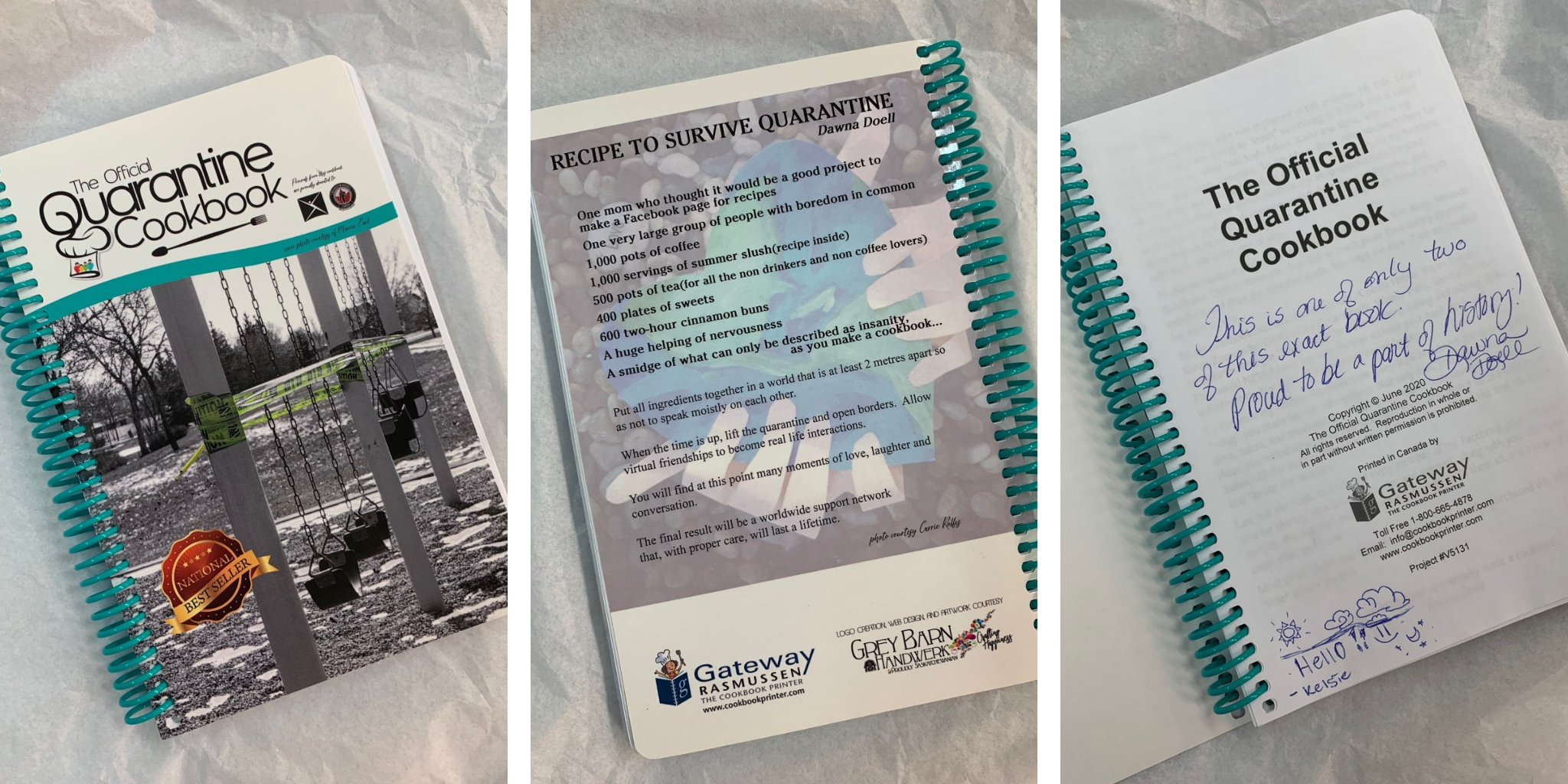

The “Official Quarantine Cookbook”

Read the blog article: “Desserts” is “Stressed” Backwards: COVID-19 and Pandemic Foodways in Canada”

Closures

Despite emergency government support, many businesses were forced to close over the course of the pandemic. It also took a toll on nonprofit organizations, including Encounters with Canada. This was a youth program about history and citizenship run by Historica Canada. We collected materials about the program that tell the story of its history and demise.

Participants in the final session of Encounters with Canada, March 2020.

Historica Canada

Read the blog article: “The closure of encounters with Canada: Collecting pandemic history”

Resistance and counter-protest

Resistance to public health regulations appeared early on. It often took the form of protests against business closures and vaccine requirements. In 2023, a major cross-country protest, the “Freedom Convoy,” descended on downtown Ottawa and led to weeks of confrontation and chaos.

Museum curators collected many objects related to the protests, including posters and flyers. We also collected material related to citizen counter-protests. Notably, this included a fake plaque created to commemorate the “Battle of Billings Bridge.” This was a confrontation where locals blockaded convoy vehicles on their way downtown.

Window signs made by the family of Robert Talbot.

Canadian Museum of History, 2022.39.

Read the blog post: “Pandemic Protests and ‘Freedom Convoy’ Context”

Read the blog post: “Collecting COVID-19 History: Protest, Resistance and Celebration”

Rights and freedoms

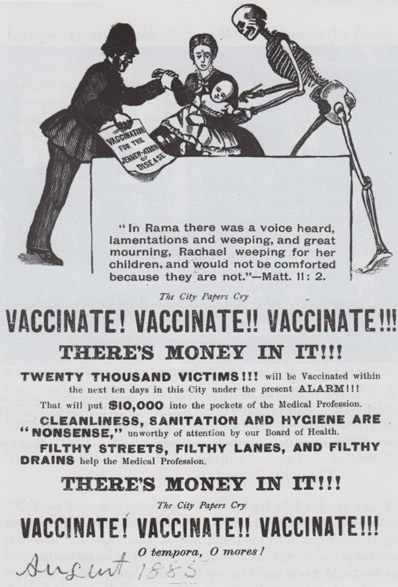

The public policy response to the pandemic raised serious and complicated questions about rights and responsibilities. There were disagreements over balancing individual freedom with collective care. From a historical perspective, these were all very familiar. Such issues had been sources of conflict in past public health emergencies. Vaccine mandates and the surrounding debates are nothing new, in Canada or around the world.

Anti-vaccination poster, 1885.

Michael Bliss, Plague: How Smallpox Devastated Montreal (Toronto: HarperCollins, 1991)

Read the blog article: “Vaccine Mandates in Historical Context”

Collecting the present

History museums have long been trusted as sources of knowledge and authority about the past. For many years, museums like ours have been working to broaden the types of stories we share. We’re actively engaged in collecting and preserving elements of the events and culture unfolding around us right now. Especially in difficult moments of crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic was in many ways a novel and transformative moment for the world and Canadians. However, it also highlighted longstanding social, economic and political currents in this country. It was important for the Museum to document and share some of the experiences from this time.

Our practice of contemporary collecting helps ensure the times we live in can be remembered, retold, and understood by future generations. The lives we live today will inspire tomorrow’s history.

Steve McCullough

Dr. Steve McCullough is the Digital Content Strategist at the Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum. His work in digital storytelling involves compassionate and evidence-based efforts to address history, meaning and identity in our fragmented and polarizing, but also vibrant and interconnected, online environment.

James Trepanier

James Trepanier joined the Museum in 2013, and was part of the exhibition team for the Canadian History Hall, which opened in 2017. He led the development of content related to diversity and human rights, 20th century social and political history, the history and legacy of Indian residential schools, and early 20th century growth and social reform.

Read full bio of James Trepanier