The year 2016 marks 100 years since women were given the right to vote in a provincial election. As obvious as it may be today to see women voting, the movement to secure votes for women was socially divisive. This important milestone in Canadian history is thus the theme of this year’s Canada History Week, held from July 1 to 7.

To commemorate the first voting rights for women in Canada, the Canadian Museum of History partnered with the Manitoba Museum on a display celebrating this significant anniversary. For this latest blog post, we invited Dr. Roland Sawatzky, Curator of History at the Manitoba Museum, to share some insights on the creation of the display.

“Nice women don’t want the vote” — these words were attributed to Manitoba Premier Sir Rodmond Roblin during a heated conversation with Nellie McClung in 1914, when the women’s suffrage movement was in full swing. Two years later, Manitoba became the first province to grant some women the right to vote.

“Votes for Women” pennant, felt, 1913–1915

Pennants and sashes were used to display loyalty to the cause. The use of gold in the North American women’s suffragist movement has its origins in the sunflower, a symbol of Kansas, where an early campaign was defeated in 1867.

Donated by Warren West, Manitoba Museum, H9-38-198

When the Manitoba Museum developed an exhibit to commemorate the 100th anniversary of these rights, we decided to use Roblin’s famous words as the title. It was a good choice: eyebrows were raised. We also wanted to do two other things with the exhibition: feature real artifacts from the period, and provide Canadians with a way to “rediscover” the story by looking at it in new ways.

The first problem with our project was that we didn’t have many artifacts from our own women’s suffrage movement. So we did what most museums do in a situation like this: we reached out to the public for help. As curator of the exhibition, I made a number of appearances on television and radio, and gave newspaper interviews.

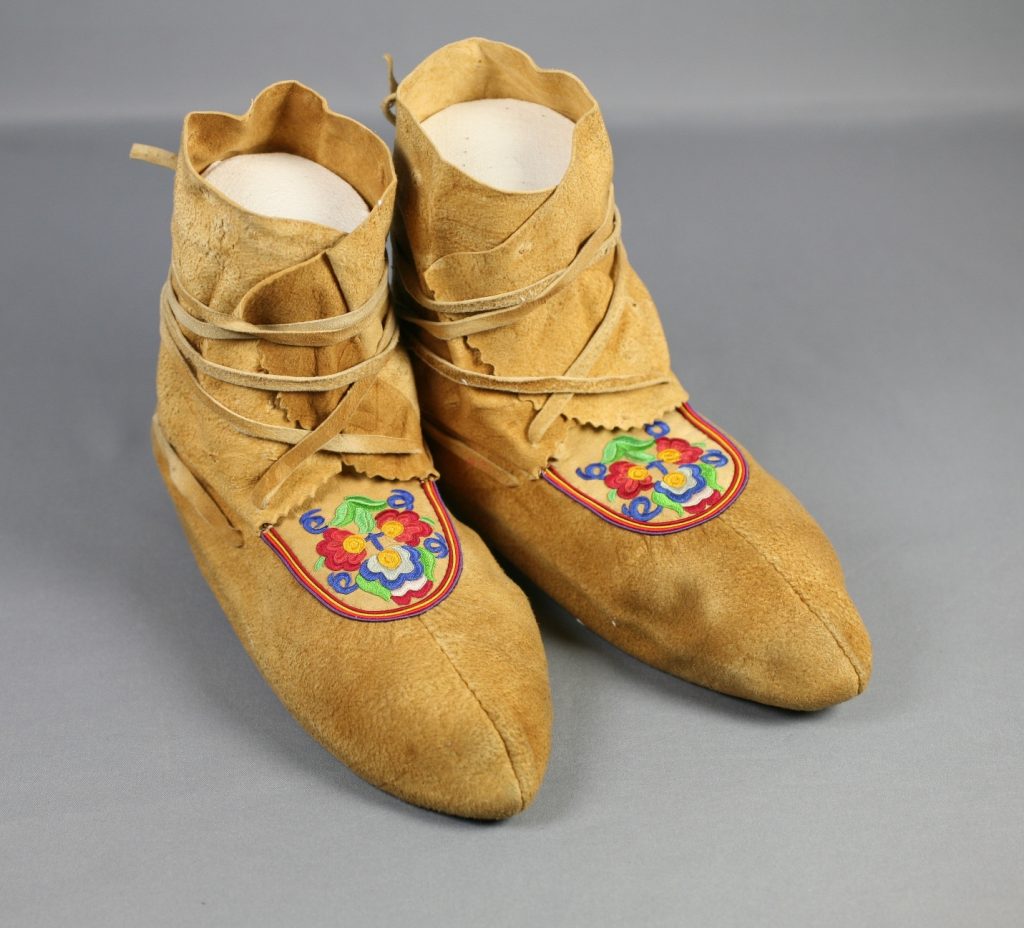

Woman’s moccasins, late 19th century, silk embroidery on caribou and moose hide, unidentified female Cree artisan, Norway House, Manitoba

While other Manitoban women won the vote in 1916, the maker of these beautiful shoes would have been denied the vote in federal elections for another 44 years.

Manitoba Museum, H4-0-779.

In the week following this media blitz, we received some interesting, unexpected and very welcome responses. The tweets and emails rolled in, with one common theme: Indigenous women didn’t get the vote in 1916. This is a topic we intended to include in the exhibition and teachers’ guides, but the issue didn’t come out in our early media conversations.

![“[NO] VOTE FOR WOMEN,” cedar siding, 1910–1915, Portage la Prairie, Manitoba This is a section of exterior wall from a house that formerly stood just north of Portage la Prairie, Manitoba. The woman living in the home painted “VOTE FOR WOMEN” on the side of her house so that it could be seen from the road. Her husband later painted “NO” above this sign. Loan courtesy of the Wishart family of Portage la Prairie, Manitoba Museum](https://www.historymuseum.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/No-Vote-for-Women-Sign-1024x823.jpg)

“[NO] VOTE FOR WOMEN,” cedar siding, 1910–1915, Portage la Prairie, Manitoba

This is a section of exterior wall from a house that formerly stood just north of Portage la Prairie, Manitoba. The woman living in the home painted “VOTE FOR WOMEN” on the side of her house so that it could be seen from the road. Her husband later painted “NO” above this sign.

Loan courtesy of the Wishart family of Portage la Prairie, Manitoba Museum

Porcelain Match Holder, 1910–1914, Schafer & Vater, Germany

This ceramic memento makes an anti-suffrage statement, equating women suffragists with “silly geese.”

Donated by Kim Semonick in memory of her grandmother Sarah Roper, Manitoba Museum, H9-38-361

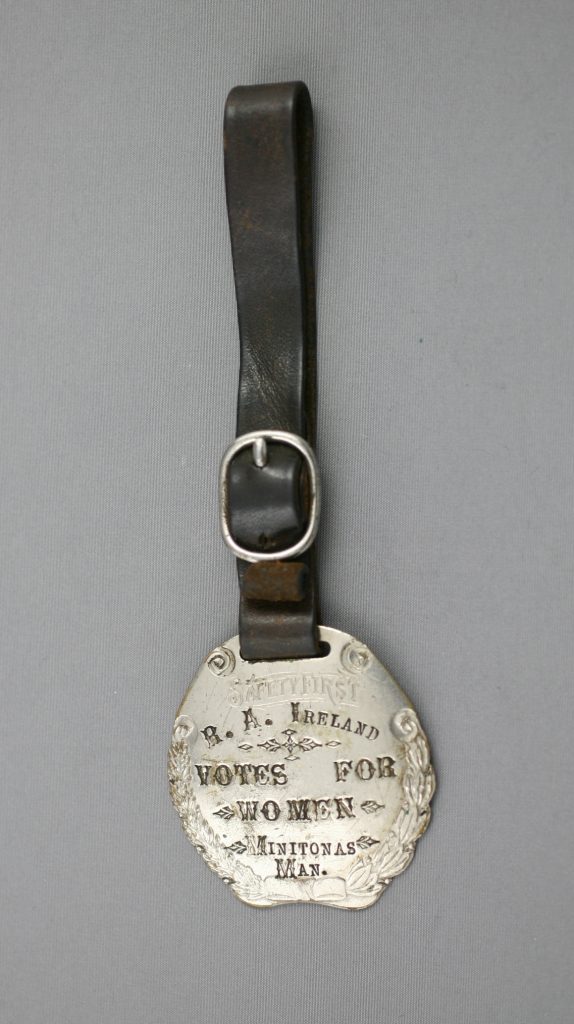

We also started to receive calls from people who had been cherishing women’s suffrage heirlooms and artifacts for decades, which they were ready to loan or donate for the exhibition. These ranged from objects as small as a watch fob to things as large as graffiti from an exterior house wall. Photographs of a women’s suffrage picnic near Roaring River, a “Votes for Women” pennant, and ceramic pieces were all gratefully accepted.

The collection reminds us that a huge grassroots movement helped push the women’s suffrage debate. For example, a replica of an 1894 petition for women’s voting rights includes over 5,000 signatures. While well-known leaders shaped the arguments, thousands of women and men from rural farms and urban factories gave the movement energy and purpose.

Watch fob owned by Roy A. Ireland, 1910s, Minitonas, Manitoba

Loan courtesy of the descendants of Gertrude Twilley Richardson and Fanny Twilley Livesay, Manitoba Museum

The collection and related exhibit also remind us that this debate was happening largely within white, English-speaking, Protestant, newcomer society, leaving out Indigenous voices, as well as many Eastern European immigrant communities. The attainment of universal voting rights for Canadians did not progress in a straight line.

Nice Women Don’t Want the Vote has completed its run at the Manitoba Museum, and is now travelling around the province. It will be presented at the Canadian Museum of History from October 5, 2016 to March 12, 2017.