This is the first blog in the series Bone Detective: Mysteries of Those Found Beneath Downtown Ottawa about the findings in the Barrack Hill Cemetery. Read the series introduction and find the link to more posts below.

I’ve worked on the Barrack Hill Cemetery project for many years and have encountered lots of interesting mysteries, some of which are being shared with you in this blog series. As the project moves forward and analysis of the individuals left behind in the cemetery progresses, puzzle pieces collected along the way — that long made no sense — finally do.

2016 excavations of burials 12 and 13

(Young, 2016)

What wood was what?

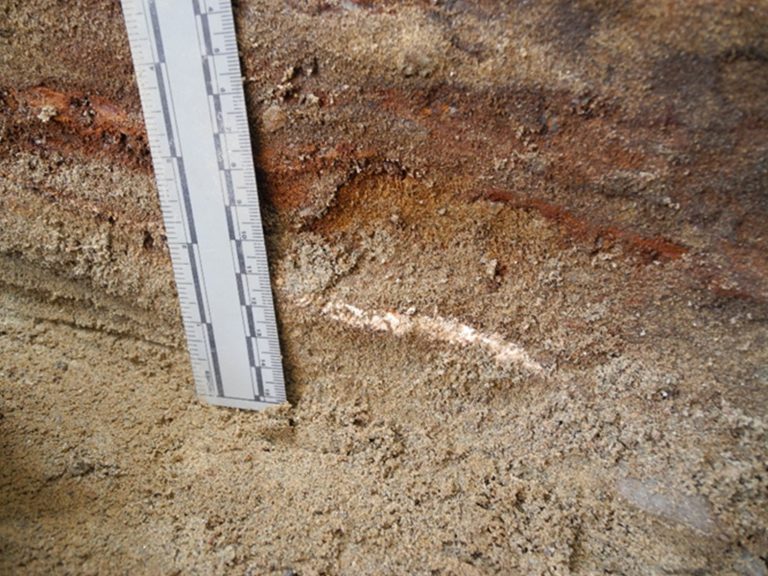

Remnants of bark found within the graves

(Young, 2016)

Early in the investigation of the cemetery and its population, I sent a sample of coffin wood for analysis. There was so much coffin wood preserved at the site, I thought it would be easy to identify what tree species was used to build the burial boxes, and fit these results into the historical context of coffins in the 19th century. When the analysis came back as inconclusive, I was shocked. Why couldn’t the wood species be identified? The answer was odd: because it was bark. I thought, “Ok, that’s a weird result,” and moved on. I mean, did it really matter that I couldn’t identify the wood? Turns out, I shouldn’t have focused on what the wood wasn’t, but rather on what it was.

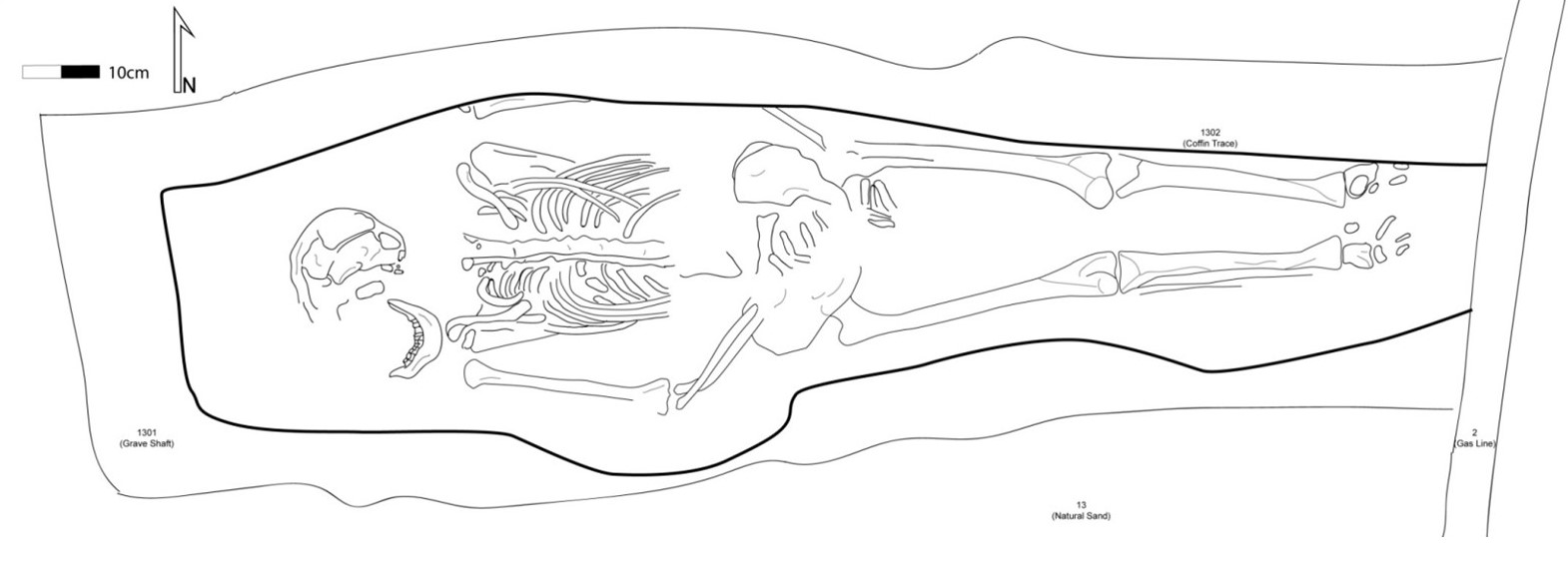

Burial 2016-13 – “The Violated”

Plan drawing of Burial 2016-13.

(Ben Mortimer, 2017)

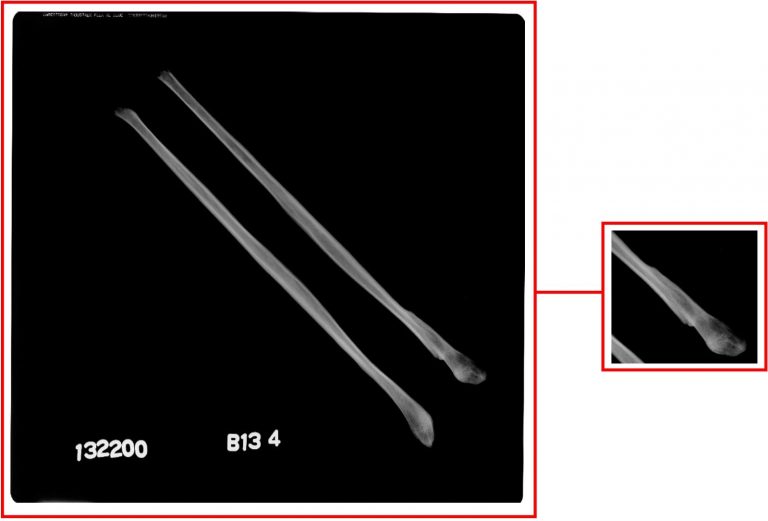

X-ray of right and left fibulae with the fracture clearly visible on the lower part of the left bone.

(Young, 2019)

The man found in Burial 2016-13 was like other adults at the site: he survived a childhood of health issues and lived into adulthood, passing away before he turned 35. He had a broken leg that never healed properly, suggesting he had limited or no access to medical help, he smoked a pipe, and he worked hard for a living.

However, unlike most others at the site, his skeletal remains had track marks and holes on many of the surfaces, and some of these holes contained a strange-looking hard substance that I’d never seen before. Was it a product of a disease process? Could it be a type of cancer? Or was it something that happened to his bones after he died? And so began the research.

Unknown accretions found below the surfaces of some bones.

(Young, 2019)

A riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma

Surprisingly enough, the key was the bark. Why would bark be inside the coffins? If you search Bytown’s past, you’ll quickly learn that it was a lumber town. From the beginning, lumber mills were established to process logs into timber. Part of that process involved squaring the logs — that is, removing the outer and inner bark and the sap wood prior to cutting the timber boards. Those squarings really had little to no value.

Even today, a whole truck load would cost about $20. What better way to make cheap coffins for the town’s lowest economic class? All you would have to do is turn the bark side of the squarings towards the interior of the coffin and, voilà! A box with no outer appearance of irregularity.

Image 1: Pine log squarings from the production of wooden planks at the 19th century Beach’s Sawmill, Upper Canada Village. Image 2: The inside base of a Barrack Hill Cemetery coffin after the skeletal remains were removed, showing an interior of bark and sap wood.

(Image 1: Young, 2023; Image 2: Young, 2017)

Did you know that 19th century Bytown was home to an extraordinary number of beetles? In fact, one species was nicknamed the “Ottawa cow” (Monohammus confusor Kirby or pine sawyer beetles) because in the evenings you could hear its larvae munching away on wood in the timber yards.

This particular species of beetle digs beneath a tree’s bark and lays its eggs. The larvae that emerge eat anything: wood, buildings, cork, books, plastic moulds, mortar, stonework of walls, lead cables, and — I am arguing — human bone, thereby creating track marks. When the larvae are ready to pupate, they burrow into the substrate and line their chambers with the waste of what they have been eating. This waste is called frass, and the strange-looking accretions that I was finding in the burrows on the bones of Burial 2016-13 is an exact match, making it a by-product deposited by the beetles as they ate their way through this man’s skeleton.

This horrible outcome for this man inspired the name ‘‘The Violated,” because, once laid to rest, his body was infiltrated by beetles that used him as a source for food and nesting, violating the sanctity of his burial and his eternal peace.

Ottawa Naturalist publication discussing pine sawyer beetles active in the Ottawa area in the late 19th century.

(Internet Archive)

Image 1: Track marks from beetles found on a support beam beneath the bark in Beach’s Sawmill, Upper Canada Village. Image 2: Beetle larvae with frass deposit similar to the deposits found in the burrows on the bones of Burial 2016-13.

(Image 1: Young 2023; Image 2: Amateur Entomologists’ Society)

Find out more

Read more about the findings in the Barrack Hill Cemetery in the blog series, Bone Detective: Mysteries of Those Found Beneath Downtown Ottawa.

Janet Young

Janet Young specializes in the study of human skeletal remains, and has been working at the Canadian Museum of History since 1994.

Read full bio of Janet Young