Figure skater Elizabeth Manley was mercilessly criticized and fat-shamed in the lead-up to the 1988 Winter Olympic Games. She nonetheless persevered, winning a silver medal and proving her critics wrong.

Manley’s Olympic team jacket is part of the collection at the Canadian Museum of History. It illustrates the patriotism and fame that comes with elite athletic performance, but her story shows that some sports and athletes are singled out for unfair and harmful treatment.

Elizabeth Manley’s Team Canada jacket from the 1988 Winter Olympic Games.

Canadian Museum of History, IMG2024-0122-0025-Dm

Mental health, silence, and stigma

Manley is widely remembered as “Canada’s sweetheart” who won a triumphant silver medal at the 1988 Olympic Games in Calgary. At the time, however, she was experiencing considerable mental and emotional stress, which was compounded by aggressive, critical media coverage.

A week before the 1988 Olympics, an Ottawa newspaper published a piece that doubted Manley’s prospects. She recalls, “The whole article talked about me having a breakdown, me suffering from mental health [issues], and people feeling that I was inconsistent at competitions. It more or less was just saying because I was diagnosed with mental health issues, that I wasn’t going to be strong enough to win a medal. I was absolutely devastated.”

Manley tried to be forthright about her struggles with depression and anxiety. But, she says, “in the ’80s, we didn’t talk about mental health.” She faced a systemic culture of silence and denial about mental and emotional health in elite sport. “Athletes are trained to be tough, and to be tough, you don’t have a voice,” she says. “You stay quiet, you keep things hidden.”

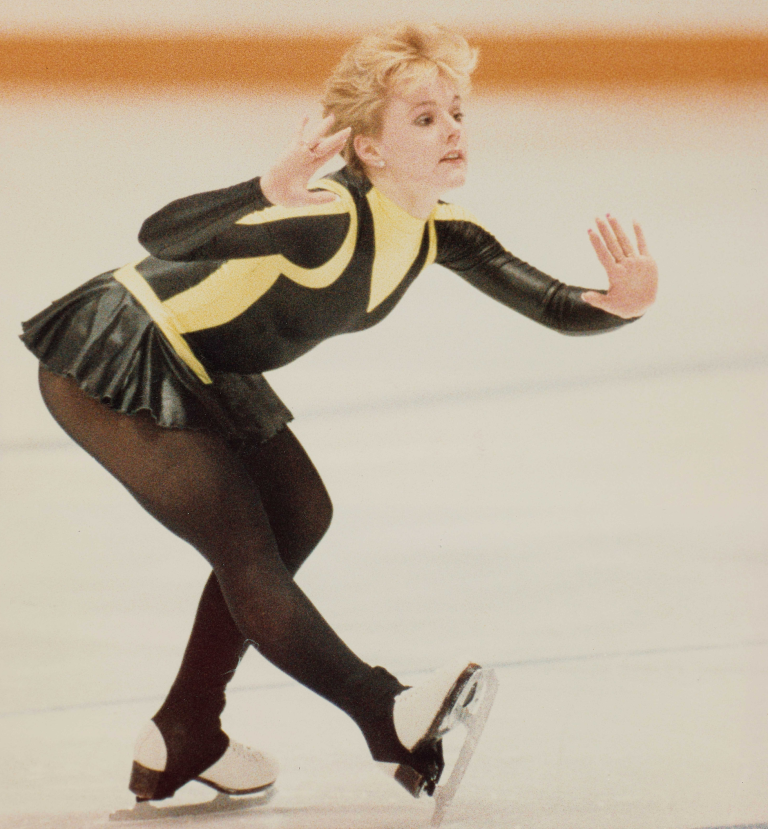

Manley in 1988, practising for the free skating routine that would earn her the silver medal.

Canadian Press/Paul Chiasson

Body image and athleticism

Something coaches and sports journalists did constantly talk about, however, was the appearance of female athletes’ bodies. There was near-constant discussion of Manley’s weight both in the media and within the figure skating world.

Chloe Ouellet-Riendeau is the Assistant Curator of Sport History at the Canadian Museum of History. She notes that journalists at the time “would really focus on the physical aspects of the depression, like the weight gain and the hair loss.” She says that there was “additional pressure put on the body image of aesthetic athletes” and that journalists focused on what women looked like, “instead of focusing on the performance of the body, of what the body was able to do, its ability.”

After her career in competition, Manley worked in the world of commercial skate performance. There, she also experienced a harmful focus on thinness and physical appearance. She says, “I worked with an ice show for three full years. I did 1,200 shows, and I was weighed every week. And if I gained one pound, I was fined. And if I didn’t lose that weight that I had gained within two weeks, I’d be fired.”

Manley being interviewed in Toronto during the 2010 Winter Olympics. She was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in 2014.

Flickr / Tyler Ingram

Evolving attitudes

In recent years, a growing number of elite athletes, such as Simone Biles, Naomi Osaka and Michael Phelps, have been vocal about their struggles with mental health.

Famously, Biles withdrew from several events in the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo when she experienced a sudden loss of focus and confidence. She took time off to work on her mental health before eventually returning to competition. Manley says, “I had so much respect for her. And you know what? The world supported her. And that warmed my heart because that’s what we need.”

In the 2024 Paris Olympics, Biles won three gold medals and one silver, making her the most decorated U.S. Olympic gymnast in history. She credits her success to prioritizing her mental health.

These days, Manley trains figure skaters and hockey players. She incorporates close attention to their mental well-being into her coaching practice. “I want them to feel in a safe place with me,” she says. “And because they know my story, they feel safe, and they can talk to me. And I get such great work out of them after that.”

This form-fitting costume was worn by Barbara Underhill at the 1983 World Figure Skating Championships. Figure skating involves both athletics and aesthetics, and the intense focus on how skaters’ bodies look can lead to body image and mental health issues.

Canadian Museum of History, IMG2024-0122-0020-Dm

New guidelines, stubborn problems

In 2020, Skate Canada released guidelines focused on body positivity. Ouellet-Riendeau says, “The guidelines are really put forward for the coaches, for anyone that’s in the vicinity of the athletes, to help them use language and practices and behaviours that are going to make sure that the athletes are protected.”

She points out that harmful attitudes and behaviours force a disproportionate number of young women to drop out of sports. “Mental health and body image is a really key factor of why a lot of them decide to drop out because the pressure is just too much,” she says.

Neither Ouellet-Riendeau nor Manley expects that these new guidelines will revolutionize the culture of elite sport overnight. Ouellet-Riendeau notes that a 2021 study found that “female athletes in aesthetic sports experience emotional abuse through body shaming.” She reports that in another recent study, figure skaters “talked about how [body expectations] led them to disordered eating and led them to injuries.” She says, “While one set of guidelines won’t immediately change the culture of elite sport, it is a step in the right direction. Each brick in the wall makes a difference.”

Ideally, says Ouellet-Riendeau, coaches and journalists should “focus more on the ability of the body, what it can do, and less so on its appearance.” As Manley says, “We’ve just got to let the athletes be athletes.”

Listen to Elizabeth Manley’s episode of Artifactuality to hear more about her struggles with stigma, and about what’s being done in the areas of mental health and body image in elite sport.

Download and subscribe to Artifactuality wherever you get your podcasts.

Steve McCullough

Dr. Steve McCullough is the Digital Content Strategist at the Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum. His work in digital storytelling involves compassionate and evidence-based efforts to address history, meaning and identity in our fragmented and polarizing, but also vibrant and interconnected, online environment.