When does a story become history?

“That is the million-dollar question,” says James Trepanier, Curator, History of Childhood and Social Movements at the Canadian Museum of History. He is one of the curators responsible for collecting artifacts that reflect how Canadians experienced the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This was an event unlike anything we had seen in our lifetimes,” he says. “When COVID first hit, we started to discuss the idea of collecting what might be seen as historic 10, 15, 50 years from now.”

Protest and counterprotest

In January 2022, tensions over COVID restrictions hit a boiling point. A massive protest convoy of trucks and other vehicles descended on downtown Ottawa. The so-called “Freedom Convoy” became an encampment, causing gridlock in the downtown core. It was eventually broken up by the federal government’s controversial exercise of the Emergencies Act.

The protesters were resisting what they called government tyranny. Many trucks blocked the street in front of Parliament while others roamed the downtown area, horns blaring and flags waving. Public transit had to be rerouted. Businesses were forced to close because so many protestors refused to wear masks. Residents reported intimidating and aggressive behaviour as well as racist and anti-science messaging from the protesters.

After two and a half weeks, some locals had had enough.

The Battle of Billings Bridge

In the middle of February, a group of Ottawa residents gathered at the corner of Bank Street and Riverside Drive, where Billings Bridge crosses the Rideau River. This is one of only a few routes north to Ottawa’s downtown.

They were there to blockade Billings Bridge to prevent more Freedom Convoy demonstrators from joining the main encampment. A few dozen counter-protesters in the morning swelled into a large crowd, hundreds strong, by the evening.

Patrick McCurdy was there. “They are self-described as moms and dads and dog walkers and they just stepped in front of some cars and blockaded them,” he says.

On that day, they blocked 35 trucks from reaching the demonstration in downtown Ottawa.

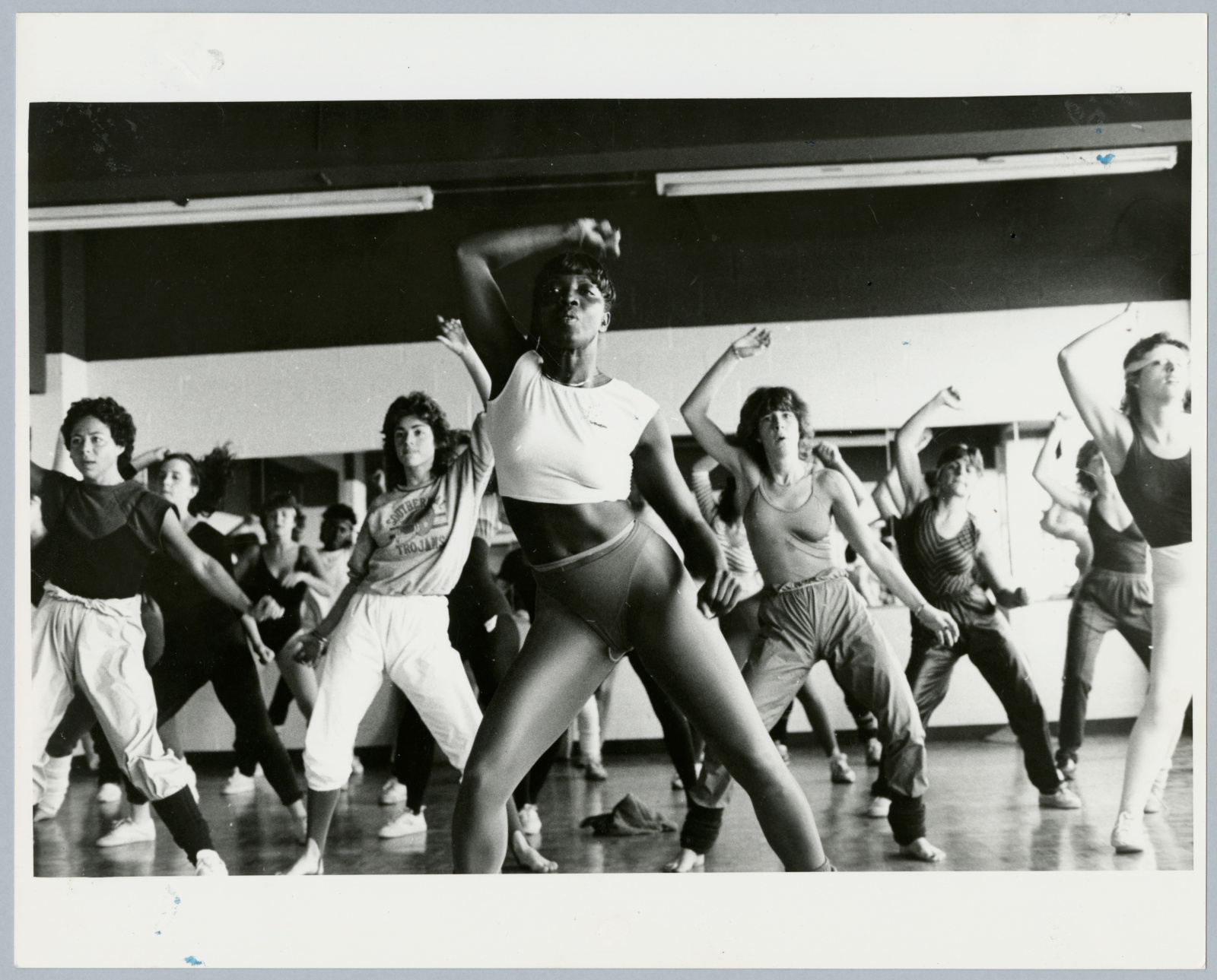

Counter-protesters gathered at Billings Bridge to prevent more trucks from joining the blockade.

Ashley Fraser / Postmedia

Satire and commemoration

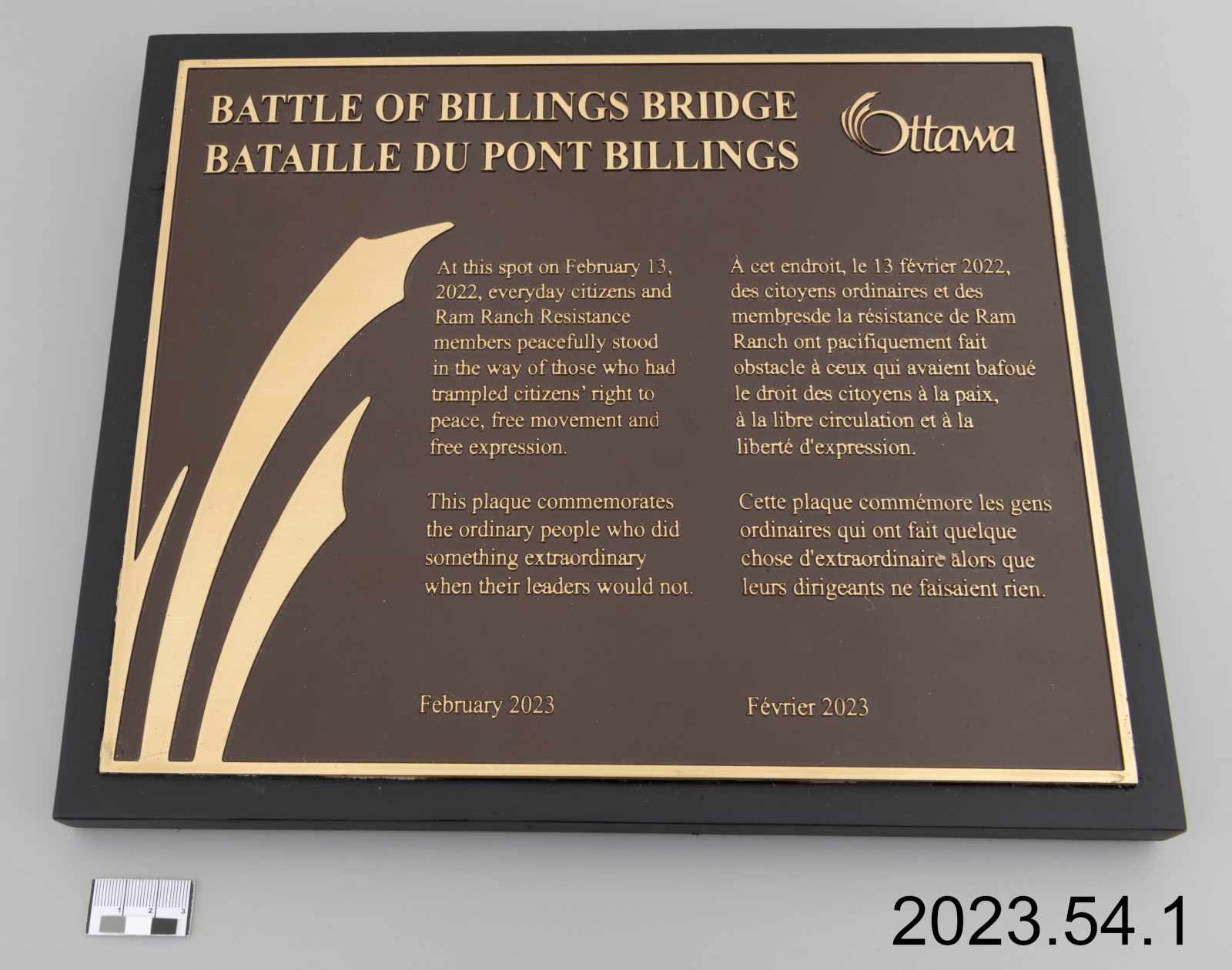

McCurdy is a professor at the University of Ottawa who studies social movements, protest and mainstream media. When the one-year anniversary of the so-called “Battle of Billings Bridge” came around, he created a faux brass plaque commemorating it. The design was intended to mimic official City of Ottawa heritage plaques.

The plaque reads:

At this spot on February 13th, 2022, everyday citizens and Ram Ranch resistance members peacefully stood in the way of those who had trampled citizens’ right to peace, free movement and free expression.

This plaque commemorates the ordinary people who did something extraordinary when their leaders would not.

February 2023

He installed it under cover of darkness. Within hours it had been stolen. But in its short lifetime, it grabbed the attention of locals and galvanized online discussion about who had created it and who had taken it down.

“Reddit was super quick to respond,” McCurdy recalls. “And the media was quick to report on this as well. I think the first story was on CTV, but quickly others followed, the Ottawa Citizen, CBC.”

McCurdy had put the plaque up anonymously, which helped stoke curiosity. He says, “From my perspective, putting it up anonymously sort of helped keep the focus on the counter-protest on the anniversary of the counter-protest. And I didn’t feel like becoming the subject of a lot of online hate, vitriol or threats.”

Patrick McCurdy’s plaque commemorating the Battle of Billings Bridge.

Canadian Museum of History, 2023.54.1

Collecting the plaque

Importantly, McCurdy had created two identical plaques. When the first plaque disappeared, he created a Reddit account in the name of the plaque, revealed the existence of the second copy, and asked for ideas about what to do.

Trepanier saw this as a great opportunity for the Museum. He says, “The plaque is really an interesting example of using commemoration somewhat subversively, but also of a particularly significant moment during the pandemic. That citizen response was a very key moment.”

He reached out to McCurdy and secured the plaque for the collection at the Canadian Museum of History.

Ephemeral pandemic history

The plaque is an intentional and durable object that tells a complicated pandemic story about policy, politics and protest. But a lot of the material culture that tells the story of the pandemic was more everyday, even throwaway. “Things like disposable masks, things that we don’t think twice about now, but at the beginning of the pandemic were quite new for many of us,” says Trepanier.

The Museum team looked around at the sudden and sweeping social changes brought about by the pandemic and sought out opportunities to collect relevant materials. The pandemic brought dramatic change, but it also highlighted persistent, systemic inequalities. Trepanier says, “We all had to live with the reality of the virus, but that reality looked different across region, class and racial status, often exacerbating existing inequalities and tensions.”

He says they asked themselves, “What kind of objects would speak to that experience of the combination of isolation of the first year in the first rounds of lockdowns, or various stay-at-home measures that were in place? And how did Canadians try to recreate their communities and sense of solidarity with each other?”

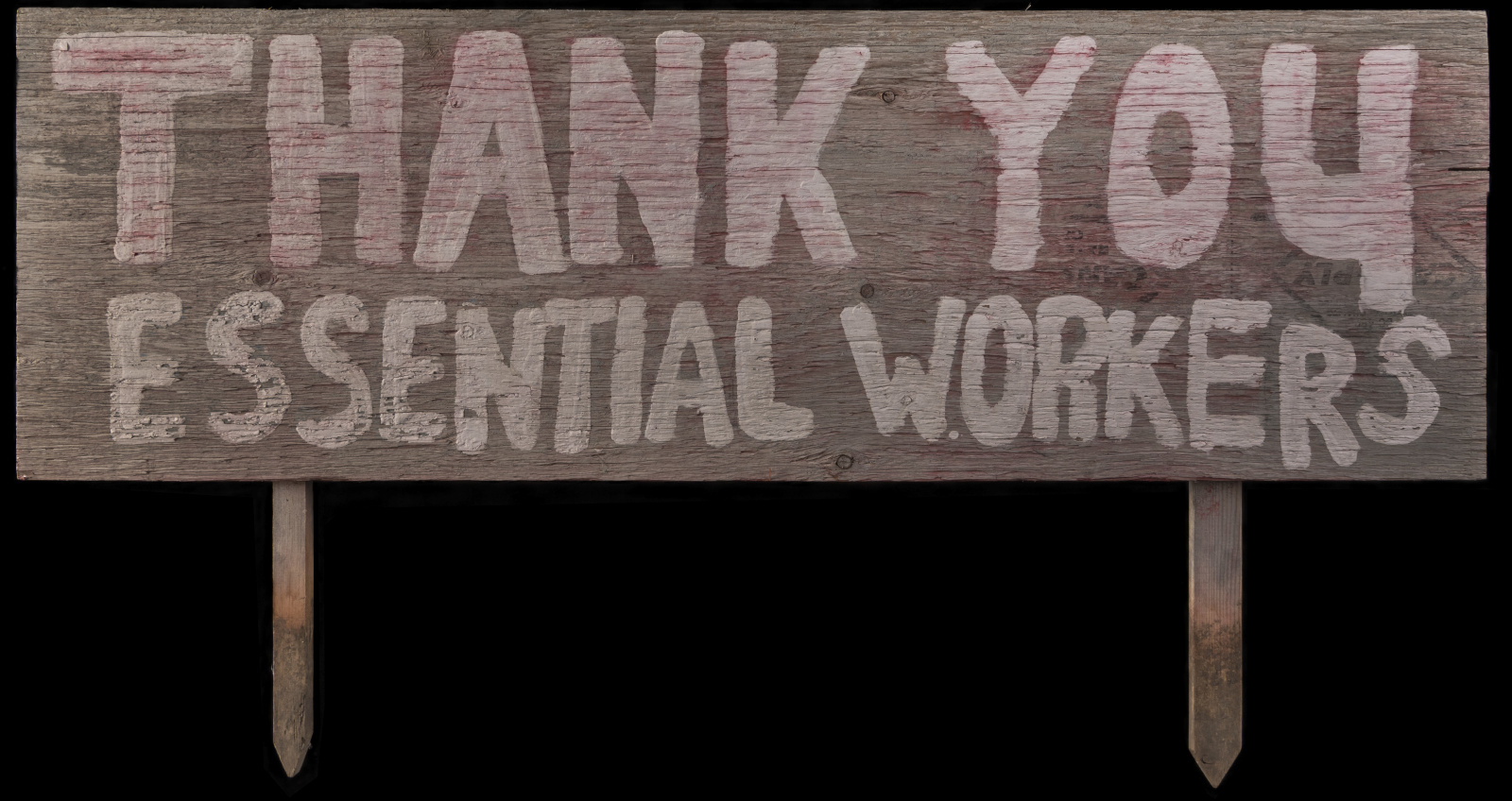

This included the many signs people put up on lawns or in windows expressing gratitude for essential workers and faith in their community. “Of course, those are very ephemeral,” says Trepanier. “Not very many people have kept those.” The Museum has collected a variety of pandemic signs, both of solidarity and protest. “Some more controversial ones would include voices and perspectives from folks who were opposed to public health measures,” Trepanier says.

Informal, handmade signs expressing support and gratitude were an important hallmark of the early months and years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Canadian Museum of History, 2021.93

History for the future

Having this collection of materials will help the Museum tell the story of the COVID-19 pandemic to future generations of Canadians. How that story is told will change as its lived memory becomes more distant.

In the next 10 or 20 years, an exhibition about the pandemic could count on visitors remembering it and sharing their stories. Trepanier says, “Having that conversation is a very intimate way to connect with the past.”

But once memories fade and the generations move on, an exhibition would have to look quite different. “Who knows where medical technology will be?” asks Trepanier. “It might seem like a very foreign thing to stick a swab up your nose to test for a virus.”

“The further you get down the line, the more foreign the past becomes,” he says. “And so, the onus to contextualize and put people back into that period gets a little higher.”

Example of cloth mask distributed by UFCW Local 401 at the Cargill meat processing facility in High River, Alberta.

Canadian Museum of History, 2021.53.1

Listen to this episode of Artifactuality to hear more about the Battle of Billings Bridge and the challenge of collecting contemporary stories in polarized times.

Download and subscribe to Artifactuality wherever you get your podcasts.

Steve McCullough

Dr. Steve McCullough is the Digital Content Strategist at the Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum. His work in digital storytelling involves compassionate and evidence-based efforts to address history, meaning and identity in our fragmented and polarizing, but also vibrant and interconnected, online environment.