What we see in an exhibit is often fabulous, intriguing, informative, or appealing, but what we don’t see can be just as fantastic. The practice of conserving and protecting fragile items is an essential but hidden element of museumship. Not mentioned on the text panels, this invisible aspect is present everywhere you look in an exhibit, and it is all thanks to a lot of preparation. No magic here—just science.

Let me take you behind the scenes in the world of preventive conservation, seen through the eyes of an archaeologist. I am the host curator for First Royals of Europe, which featured items spanning 6500 years of history. My first experience in a large, epic exhibit gave me the chance to become more familiar with conservation techniques. Because presenting thousands-of-years-old objects to the public is not without its risks.

Long before a museum receives an exhibit, conservation work begins. As the design of the exhibits gets confirmed, the materials that will be used in the display are rigorously selected and tested.

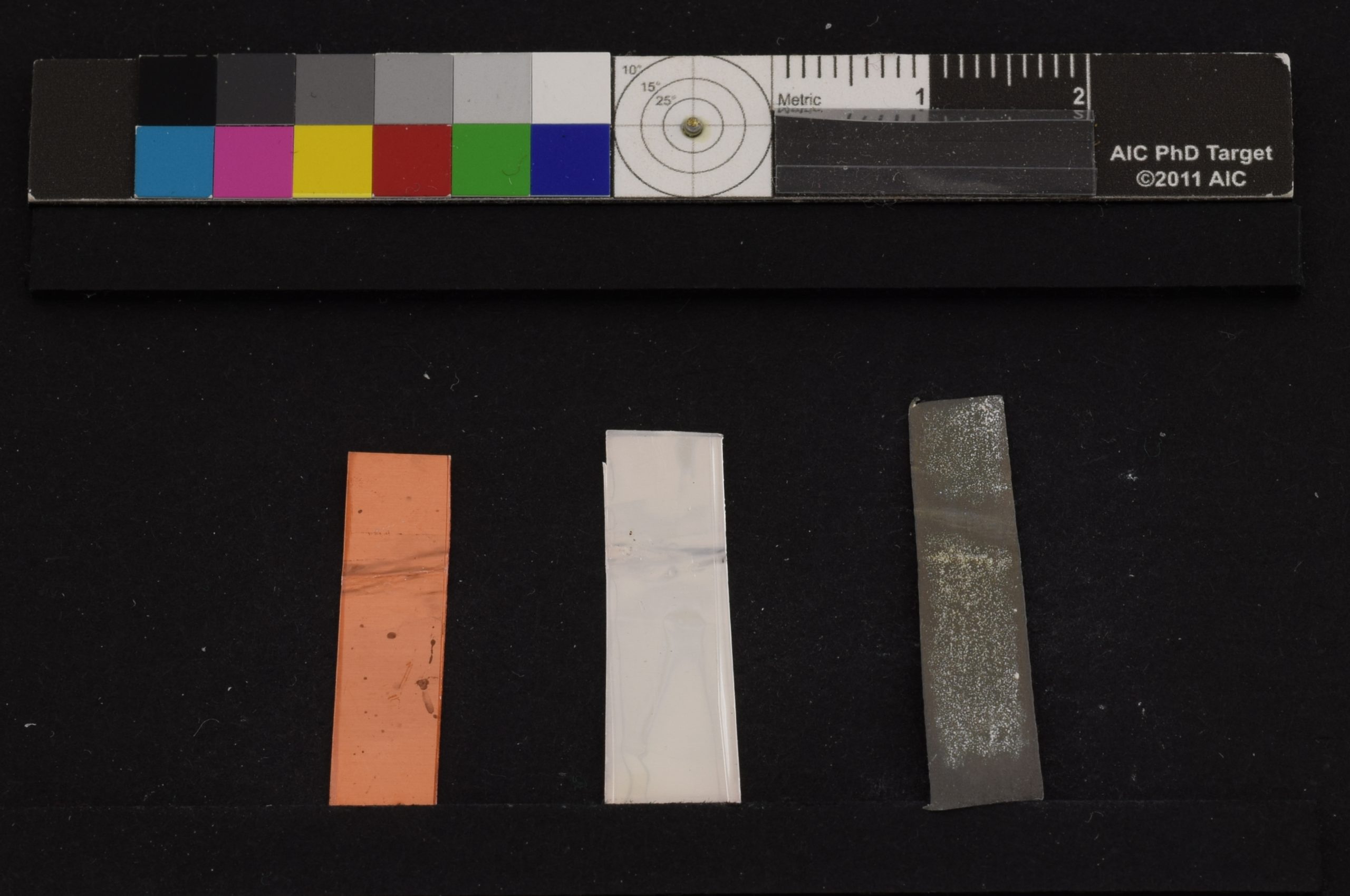

From the type of wood used for the display cases, to the paint colours and the fabric of the cushions holding the objects—everything has to be tested. We place those materials in glass jars along with metal coupons—thin films of copper, silver, and lead—and heat them in a lab oven. The heat accelerates the release of gases, causing reactions like corrosion on the metal coupons, simulating what would happen over time inside a display case. Any materials that fail these tests—proving unsafe for artifacts—are removed from consideration for use in exhibit construction.

Along with this, conservators will review the list of expected artifacts and ensure that the display conditions, such as light intensity, relative humidity, and temperature, are all carefully planned.

Artifacts are usually preserved in the dark in a stable environment with specific humidity and temperature. When we present them to the public, we need to make sure the lighting and environmental conditions are appropriate for the entire duration of the exhibit. Most of them will be placed on convenient supports and sealed inside display cases to maintain the precise environment they need.

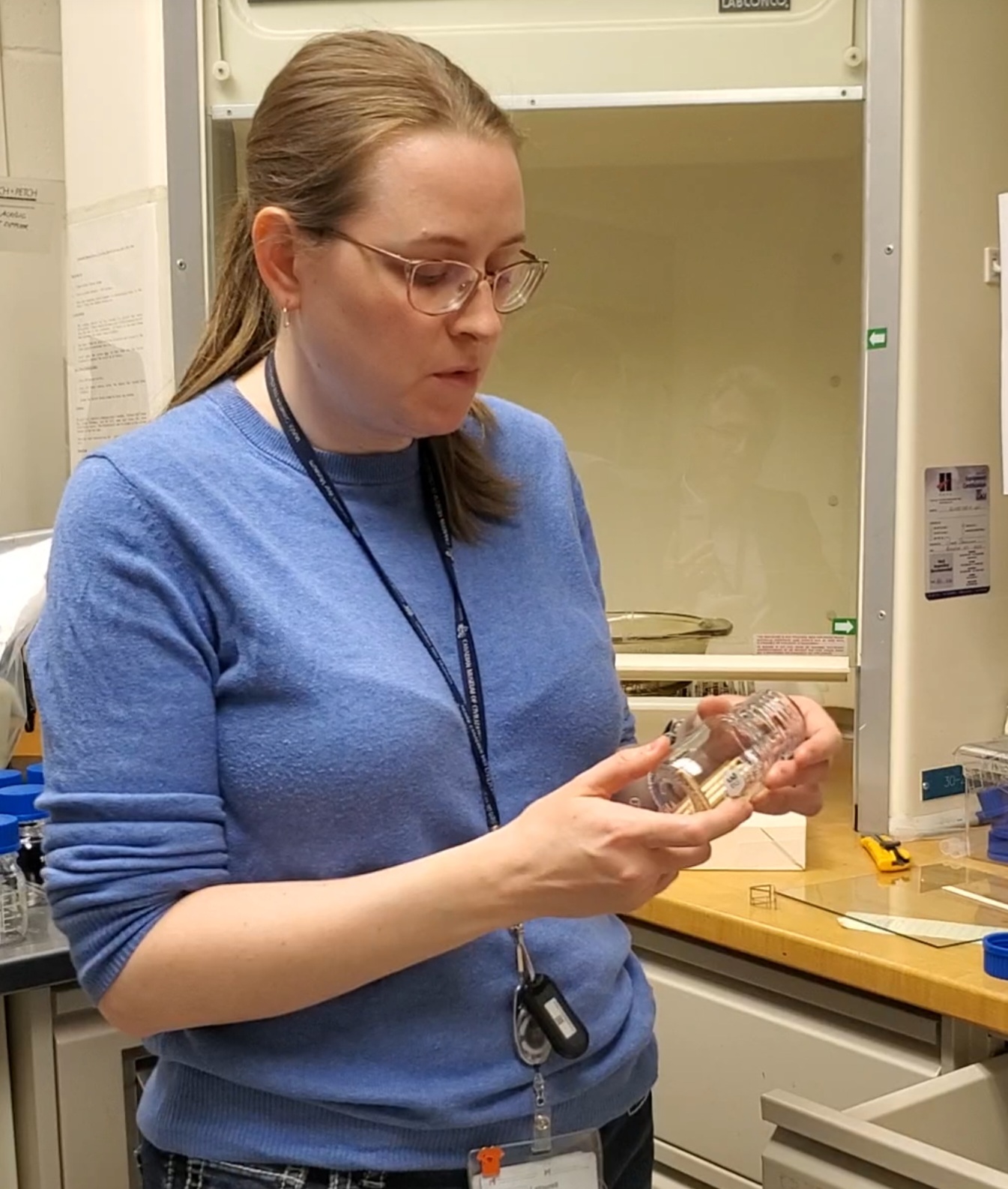

Rebecca Latourell showing the glass jar and metal coupons used for the testing.

Canadian Museum of History

Metal coupons showing oxidation. The material failed the test.

Canadian Museum of History

When the artifacts finally arrive at the museum, it is a well-orchestrated event. Security is increased near the loading dock, and the collection team carefully transports the cases to the vault. After unpacking, conservators perform a thorough condition check of the objects to look for any changes that may have occurred during transportation.

A condition report is created based on a visual inspection of the objects, comparing them with good-quality photos provided earlier. Any signs of damage, such as corrosion, chipping, or cracking, are noted. In some cases, we might need to perform emergency treatments to stabilize an object and ensure it is in fit condition for display throughout the exhibit.

While display cases may look sharp and showcase the craftsmanship of their makers, there is more than just visual beauty at play. They are filled with technology and scientific know-how. This invisible aspect is sometimes revealed by the presence of a data logger, tucked away in the back corner of a display case. But even this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Depending on the composition of the objects and their specific environmental needs, we might add silica gel to regulate humidity levels, activated charcoal or a product like Purafil to absorb pollutants in the air. Purafil is a irreversible absorbent product that changes colour as it gets saturated with moisture while activated charcoal is a reversible absorbent. Mechanical thermohydrometers and digital data loggers help us monitor the conditions inside the display cases. Some loggers just give us a visual reading, while others constantly record data that we can download using a Bluetooth application.

The First Royals of Europe exhibit is organized according to the history of material culture – Copper Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age, and so on, with displays of items made of (no surprise!) copper, bronze, and iron. Although they are generally older, the copper and bronze items are more resilient to the passage of time than iron. Iron may have been widely used in the Iron Age, but despite its strength and versatility, it does not survive the test of time well. An archaeologist finding an iron sword on an Iron Age site would certainly be delighted!

So, it is no surprise that displaying such objects requires extra care. To protect them, the rare iron objects are displayed under low light and in very low humidity.

Mechanical thermohydrometer located in one of the display cases.

Canadian Museum of History

Emily and Rebecca setting up one of the display cases.

Canadian Museum of History

A microclimate generator is used to maintain a very low humidity level inside a showcase, like the two that contain iron objects in this exhibit. Even though display cases are sealed, the air inside always tries to reach equilibrium with the outside air. This active device thus keeps the relative humidity level under 25 percent. By combining it with silica gel, we are able to further lower the relative humidity level.

As a glimpse into the world of conservation, I hope you now have a better understanding of the work, science, and technology hidden behind the scenes of the display cases.

On a larger scale, you might also notice the steady humidity level and temperature inside the museum, always the same with each visit. This means the entire building must be carefully conditioned in the same way. I often joke that this is an advantage of working in a museum, as it may preserve me well and grant me longevity.

Pierre Desrosiers

Pierre Desrosiers joined the Museum in 2019 following extensive experience working with Indigenous Peoples in northern Quebec. As Curator of Central Archaeology, he oversees collections related to Ontario and Quebec, and is interested in the intergenerational and intercultural sharing of technologies — particularly the ingenuity of material knowledge and skills.

Read full bio of Pierre Desrosiers