The Explorers

Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville 1686-1702

Baptised at Ville-Marie on July 20, 1661, Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville is the third of eleven boys and three girls born from the marriage of Catherine Thierry-Primot to Charles Le Moyne de Longueuil, a merchant in Montréal. D’Iberville, who was trained to wield an incisive and nimble pen, was sufficiently well brought up to be comfortable in the presence of the king and his ministers and crafty enough to use both cruelty and generosity as he saw fit. If he had been the governor of New France and if death had not taken him on the island of Cuba when he was only 45, North America might have ended up being French…

Routes

Baptism of fire

Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville was born in a time when one had to fight to survive in New France. The island of Montréal, located at the junction of the paths leading to the Great Lakes and Hudson’s Bay, since its founding in 1642, was vulnerable to Iroquois attacks. Ville-Marie is at the heart of the fur trade and the local merchants are prospering. Lemoyne’s father, Charles Le Moyne, who started with nothing and was given a noble title in 1668, was one of the richest and most influential pioneers in this new-born city. A partner in several trading companies, he took part in the creation of the Compagnie du Nord or the Compagnie française de la Baie d’Hudson in 1682.

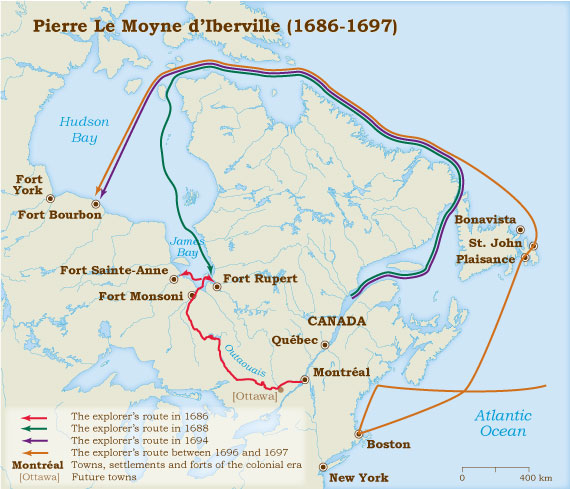

In 1685, the investments made by the Compagnie du Nord in Hudson’s Bay are threatened but the company gains the support of the governor, Jacques-René de Brisay, marquis de Denonville. It is now in a position to finance an expedition to Hudson’s Bay in 1686. Three of Charles Le Moyne de Longueuil’s sons take part: Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, Jacques Le Moyne de Sainte-Hélène and Paul Le Moyne de Maricourt. This lightning campaign gives the French control over three trading posts located south of James Bay: Monsoni (Moose Factory), Rupert (Charles) and Quichichouane (Albany).

The man from Hudson’s Bay

Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville is only 25 years old when, on August 10, 1686, the chevalier Pierre de Troyes entrusts him with the command of the posts which have just fallen to the French. D’Iberville becomes a freebooter. Marauding around the Nelson River, he captures two English ships. These seizures allow him to avoid starvation and to resupply Fort Monsoni. When he returns to Québec by sea near the end of October 1687, his ship is overloaded with furs and English merchandise.

While in France during the winter of 1687-1688, he manages to convince Versailles to provide support for the Compagnie française de la baie d’Hudson thereby ensuring the French presence in the north will be reinforced. His arguments carry the day. The king places Le Soleil d’Afrique, the newest and fastest of his ships, in d’Ibervilles hands. On August 3, after a detour to Québec, this vessel could be found cutting its way through the ice in Hudson’s Bay.

D’Iberville then asked to be allowed to take Fort York, which would prevent the English from using the Nelson River or reaching the territories in what is now Manitoba. With fewer than 20 men, he boards two English ships, captures almost 80 Englishmen and ensures that the French king’s flag flies over the forts on James Bay. On September 12, 1689, with a vessel armed with 24 cannons and loaded with thousands of beaver pelts, he sets sail for Québec.

Crusader and freebooter

D’Iberville believed that the presence of the English at Fort Nelson augured the loss of New France. He draws up a simple and inexpensive plan to save the colony, once and for all. Its implementation is delayed by three events. First, the cease-fire between France and England, which had been negotiated in 1687, ended in late May 1689. Second, the repercussions of the European conflict affected the region of Montréal where, on August 5, 1689, the residents of Lachine were attacked and massacred. Finally, Governor Frontenac organized a counterattack in which D’Iberville enthusiastically took part. On February 18, 1690, an attack on Corlaer (Schenectady, New York) ends with the pillaging and burning of the town and the massacre of approximately 60 townspeople.

D’Iberville spends the winter of 1690-1691 at Hudson’s Bay but he does not accomplish anything of note. In 1693, while he is escorting the ships that shuttle between the Gulf of the Saint Lawrence and the French ports, England recaptures the forts at James Bay. In August 1694, d’Iberville returns to Hudson’s Bay holding a three-year monopoly on trade there. On October 13, he finally captures Fort Nelson. The following year, he is assigned to patrol the Atlantic, from Maine to Newfoundland.

On August 15, 1696, he adds to his mythic status by securing Fort William Henry at Pemaquid, on the coast of Maine. Without delay, he then heads for Newfoundland where, with fewer than 200 men, he takes Fort Saint John, subjugating Newfoundland by means of murderous raids. However, he is not given much time to savour his victory as he is ordered to proceed immediately to Hudson’s Bay where the forts have been retaken. On September 5, 1697, Le Pélican, leading a convoy of four ships, comes under attack. D’Iberville sinks one ship, seizes another and sends a third one fleeing.

By the time reinforcements arrive, the battle is over. All that is left to do is to retake Fort Nelson, which falls on September 13, 1697. However, his victory is in vain, since the Treaty of Ryswick, signed a week later, enshrine English dominance in Hudson’s Bay and French hegemony in James Bay. France holds on to Port Royal and Placentia but must yield Pemaquid and part of Acadia. D’Iberville’s conquests were for naught.

Louisiana bound

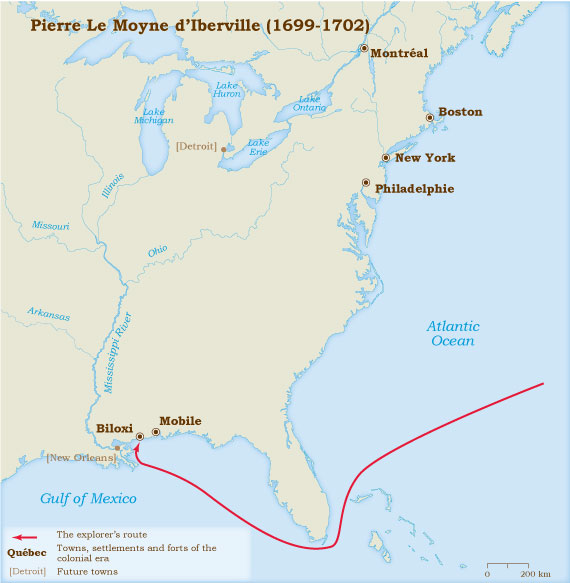

Forced to look elsewhere but still dreaming of giving North America to France, d’Iberville argues for the establishment of a French colony at the mouth of the Mississippi : “If France does not seize this most beautiful part of America and set up a colony, […] the English colony which is becoming quite large, will increase to such a degree that, in less than one hundred years, it will be strong enough to take over all of America and chase away all other nations.” His plan is to strangle the New England colonies between Canada in the north, the Gulf Mexico and Louisiana in the south and the Mississippi River in the west.

On March 2, 1699, he succeeds where Robert Cavelier de La Salle failed: travelling by sea, he discovers the mouth of the Mississippi. Three consecutive expeditions, in 1699, 1700 and 1701, allow him to built the forts of Maurepas (Biloxi), Mississippi and Saint-Louis (Mobile). In 1702, having won the trust of the natives, the commander of Louisiana leaves that colony, never to return.

The Death of General Dom Pedro Berbila

At the beginning of 1706, d’Iberville is spreading fear throughout the English Antilles. He terrorizes, pillages and neutralizes the island of Nevis. The settlements in New England brace themselves, expecting the worst. Shortly thereafter, he stops off in Havana, apparently to sell French iron. He dies there, on board the Juste, on July 9, 1706, laid low by an epidemic or fevers that had been weakening him since 1701.

The remains of the man the burial records identify under the name of ” El General Dom Pedro Berbila ” were laid to rest in the church of San Cristobal in Havana. He was 45 years old. The investigation which had been started shortly before his death, revealed that the “Cid” of Canada was a greedy man and that his lust for conquest had as much to do with his desire for financial gain as it did with his dedication to France.